Lending a helping hand

Many proteins, the primary building blocks of life, depend on elements such as copper, zinc and other trace elements to function properly. “Some metal molecules are required as a structural component for proteins, while others are used as catalytic cofactors,” explains Ayako Fukunaka, a researcher working with Makoto Hiromura and Shuichi Enomoto at the RIKEN Center for Molecular Imaging Science in Kobe.

Specialized zinc transporter (ZnT) proteins help maintain a steady supply of zinc for various proteins that incorporate this element. Now, new work from this RIKEN team, in collaboration with Taiho Kambe’s group at Kyoto University, has revealed an additional mechanism by which ZnTs contribute to the production of certain zinc-binding proteins.

The enzyme called tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) incorporates zinc while undergoing processing in the secretory pathway, a system that subsequently delivers the mature enzyme to the cell membrane. In a series of prior studies, the researchers determined that cells fail to produce stable, functional TNAP in the absence of two particular ZnT complexes. “However, we still did not know whether TNAP degradation results from a decrease in zinc content, lack of ZnT proteins, or both,” says Fukunaka.

To resolve this, she and her colleagues tinkered with cellular expression of ZnT5, ZnT6 and ZnT7, the three proteins that compose these essential zinc-transporting complexes. In the absence of these factors, levels of TNAP dropped dramatically. However, this decrease was only slightly mitigated by treatment with a compound that promotes zinc uptake, suggesting that these proteins also contribute to TNAP production via a second, parallel mechanism.

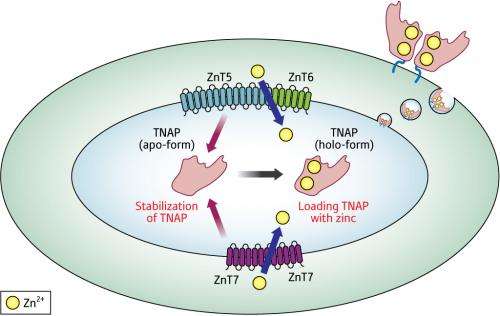

At an early stage in the secretory pathway, TNAP undergoes chemical modifications that render it resistant to degradation. Fukunaka and her colleagues determined that ZnT complexes appear to facilitate this stabilization. Experiments with mutated versions of these proteins indicated that this stabilization is independent of ZnT-mediated zinc transport, which only becomes important once the immature enzyme has been sufficiently protected against degradation (Fig. 1). “We named this phenomenon the elaborate ‘two-step mechanism', in which TNAP protein stabilization by ZnT complexes is followed by conversion of the enzyme to its mature form through the loading of zinc by ZnT complexes,” says Fukunaka.

This dual role for the ZnT proteins is as mysterious as it is surprising, and the researchers are now working to clarify the details of this process and determine whether similar mechanisms are also involved in shepherding other zinc-containing proteins to maturity.

More information: Fukunaka, A., et al. Tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase is activated via a two-step mechanism by zinc transport complexes in the early secretory pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 16363–16373 (2011).