Sugar: UCSF's Lustig on why we love it, and how it's killing us

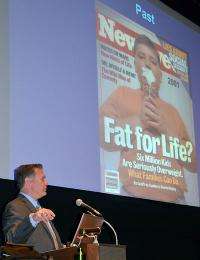

It’s not calories that are making us obese — it’s sugar. That’s the message one of the nation’s best-known experts on obesity, UCSF’s Dr. Robert Lustig, is spreading far and wide like Johnny with his apple seeds. Thursday, he brought it to UC Berkeley.

Balancing calories consumed with exercise has been the American medical and nutritional establishment’s formula for maintaining a healthy weight since the trend toward swelling waistlines first raised alarms back in the 1980s.

“We’ve been saying that for 30 years. Look where it’s gotten us,” Lustig told his audience at the Berkeley Art Museum Theater, in a two-hour presentation sponsored by University Health Services as part of its Health*Matters Wellness Program.

Where has it gotten us? More Americans than ever are obese — some 120 million, predicted to rise to 165 million by 2050. Worldwide, the story is the same; data tracks a clear association between the rise in sugar consumption and fast-increasing obesity and diabetes. Chronic diseases related to obesity now pose a bigger health threat worldwide than infectious diseases. In a rapid-fire series of slides showing maps, charts and graphs, Lustig roared through the damning statistics to set up his main point.

“Very clearly, we are going downhill — unless we do something, now,” said Lustig. “It is not about calories.”

Doing something, in Lustig’s view, means doing something about sugar. A little is fine, he says, but too much is toxic.

Calorie for calorie, sugar makes us fatter than other foods, he showed, rolling out study after study from his own research and practice. Especially implicated in this country is fructose. It makes up half of table sugar, more than three-quarters of popular alternatives like agave syrup, and because it’s cheap to manufacture from corn, it’s the sweetener of choice in soda, breakfast cereals, breads and most of the processed foods that line grocery shelves.

What Lustig’s research shows, as he explained it, is that fructose is different from glucose, sugar’s other half, because it has to be processed by the liver, like a cocktail. Glucose can be used directly by the body, which has a clever process for summoning insulin to help ferry the sugar to cells and to send hormonal signals when it needs energy or has had enough. Fructose, waiting its turn for processing in the liver, builds up in the blood and the body’s clever messaging systems are disrupted. The result: People keep eating and don’t feel like exercising, fat builds up in the wrong places; and insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes and obesity are inevitable. Glucose and other sugars follow different pathways, he says, but reach similar endpoints.

Lustig is the first to admit that his view isn’t embraced by the medical establishment, including the national Institute of Medicine, the health arm of the National Academy of Sciences, which sets food guidelines for the country. He was interviewed for a forthcoming HBO series on obesity (“The Weight of the Nation,” premiering May 14), but says his views about sugar and calories were sliced out; the IOM is the series’ main sponsor.

But evidence shows that the public is hungry for answers and is listening to Lustig. More than 2 million people have watched his 89-minute video on UC’s online TV channel, “Sugar: The Bitter Truth,” where he lays out the complicated biochemistry of sugar metabolism. A nine-minute version of his argument, “Sickeningly Sweet,” is part of “The Skinny on Obesity” series on obesity now up on UCTV Prime.

At BAM, a good crowd came out despite rain and “dead week” to hear him, and kept him talking for twice his allotted time with questions — about low-carb diets (they aren’t the answer for most people), omega 3 fats (eat wild fish), meat (we need some, for the amino acids), and how much alcohol is OK (a little is good, not too much) — that finally had to be cut off.

Lustig tailors his talk for his audience. He can make it superscientific for a medical crowd, or simplify the science for consumers, as he did Thursday. He’s making the rounds as a speaker in preparation for the January release of his new book, Fat Chance, which covers other parts of the weight-and-health equation like fats, diets and exercise, and aims for the consumer market.

His current version of his talk uses a Darwinian filter, and is titled, “Darwin, Diet, Disease, and Dollars: An Evolutionary Argument for What’s Making Us Fat.”

Obesity has existed since humans have, Lustig said. But it was rare until now. Why? Charles Darwin, the pioneering evolutionary scientist, would say rampant obesity “is a mismatch between our environment and our biochemistry.”

Long story short, in Lustig’s view: Humans’ taste for sugar is hard-wired, “engraved in our DNA;” Sugar can mask other flavors, or lack of flavor, in foods. (“You can make dog poop taste good with enough sugar, and the food industry knows it.”). Our food supply is awash is sugar, and we buy it because we like it. That has made the food industry rich, so it has no motive to change, fending off criticism with the mantra that eating is all about individual choice. And the U.S. government, which spends billions on health and nutrition policy, has been bought off by the food industry.

“When does (sugar) become a public-health problem?” he asked. He thinks sugar should be regulated as smoking and drugs are, for the same reason: because its use affects not just the people who consume it but other people, too. Chronic diseases related to obesity raise health insurance premiums by 50 percent, for example. “Are you happy with that?” he asked.

Lustig’s solutions to the problem bring his research and medical experience into alignment with the modern sustainable food movement, and might sound familiar to an audience in Berkeley, a wellspring of the modern sustainable food movement. His advice — both for the nation and for people trying to be healthy — sounds much like the words of author Michael Pollan, a professor at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, whose book “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” and subsequent tracts have been influential:

“Eat real food” — meaning food that is grown in the ground, grass-fed meats; avoid processed foods. And push for a “new food model,” one that moves away from the industrial system.

Government is not going to do this on its own, and people aren’t going to vote for change unless they understand the problem, Lustig said, adding, “That’s where I come in.”