Identification of developmental 'master switch' helps scientists explore function of infection-preventing cells

Every bite of food or drink of water is an invitation for potentially harmful bacteria and viruses to set up shop in the body. In order to protect against such invaders, the mucous membrane that lines the intestine contains clusters of specialized microfold cells (M cells), which can absorb foreign proteins and particles from the digestive tract and deliver them to the immune system.

New work from Hiroshi Ohno's group at the RIKEN Center for Allergy and Immunology in Yokohama, in collaboration with Ifor Williams and colleagues at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, has revealed valuable insights into how these M cells develop. Previous research from Williams' group showed that a signaling protein called RANKL switches on M cell development but virtually nothing was known about the subsequent steps in this process. To find out, Ohno and Williams looked for genes that get switched on when intestinal cells undergo differentiation in response to RANKL exposure.

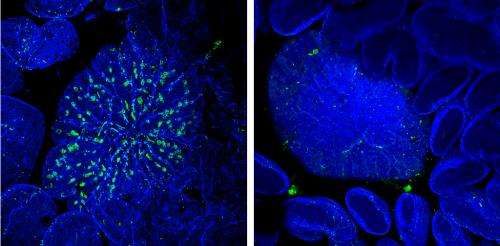

They discovered that treatment with RANKL causes immature intestinal epithelial cells to sharply increase the production of Spi-B, a protein that regulates the expression of other developmental genes. To test the specific contribution of this protein to M cell maturation, the researchers collaborated with Tsuneyasu Kaisho's group at Osaka University, which had engineered a genetically-modified mouse strain lacking the gene encoding Spi-B. The resulting animals were devoid of mature M cells. On the other hand, intestinal development as a whole was unaffected by the absence of Spi-B, demonstrating that this protein's impact is limited to this specific class of cells within the gut.

M cells normally localize to immune structures known as Peyer's patches (PPs). Bacteria such as Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) will normally accumulate within these PPs shortly after inoculation. This uptake was considerably reduced in Spi-B-deficient mice, indicating the absence of a functional M cell population. The mice showed a considerably weakened immune response following oral administration of S. Typhimurium bacteria relative to wild-type animals, demonstrating the importance of M cell-mediated microbial uptake.

The identification of this critical 'master switch' for M cell development opens exciting new avenues of research into these mysterious cells. Ohno is eager to investigate the details of how the cells perform their critical immunity-training function. "These questions could not be answered previously because of the lack of M cell-deficient mice," he says. "But now, 'knockout' mice that specifically lack Spi-B in their mucosal epithelium will provide the ideal tool for such studies."

More information: Kanaya, T., Hase, K., Takahashi, D., Fukuda, S., Hoshino, K., Sasaki, I., Hemmi, H., Knoop, K.A., Kumar, N., Sato M. et al. The Ets transcription factor Spi-B is essential for the differentiation of intestinal microfold cells. Nature Immunology 13, 729–736 (2012). www.nature.com/ni/journal/v13/n8/abs/ni.2352.html

Knoop, K.A., Kumar, N., Butler, B.R., Sakthivel, S.K., Taylor, R.T., Nochi, T., Akiba, H., Yagita, H., Kiyono, H. & Williams, I.R. RANKL is necessary and sufficient to initiate development of antigen-sampling M cells in the intestinal epithelium. The Journal of Immunology 183, 5738–5747 (2009). www.jimmunol.org/content/183/9/5738.abstract