Scientists accelerate aging in stem cells to study age-related diseases like Parkinson's

Stem cells hold promise for understanding and treating neurodegenerative diseases, but so far they have failed to accurately model disorders that occur late in life. A study published by Cell Press December 5th in the journal Cell Stem Cell has revealed a new method for converting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into nerve cells that recapitulate features associated with aging as well as Parkinson's disease. The simple approach, which involves exposing iPSC-derived cells to a protein associated with premature aging called progerin, could enable scientists to use stem cells to model a range of late-onset disorders, opening new avenues for preventing and treating these devastating diseases.

"With current techniques, we would typically have to grow pluripotent stem cell-derived cells for 60 or more years in order to model a late-onset disease," says senior study author Lorenz Studer of the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research. "Now, with progerin-induced aging, we can accelerate this process down to a period of a few days or weeks. This should greatly simplify the study of many late-onset diseases that are of such great burden to our aging society."

Modeling a specific patient's disease in a dish is possible with iPSC approaches, which involve taking skin cells from patients and reprogramming them to embryonic-like stem cells capable of turning into other disease-relevant cell types like neurons or blood cells. But iPSC-derived cells are immature and often take months to become functional, similar to the slow development of the human embryo. As a result of this slow maturation process, iPSC-derived cells are too young to model diseases that emerge late in life.

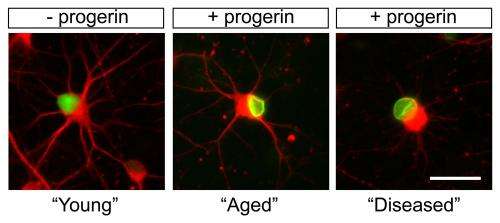

To overcome this hurdle, Studer and his team exposed iPSC-derived skin cells and neurons, originating from both young and old donors, to progerin. After short-term exposure to this protein, these cells showed age-associated markers that are normally present in old cells.

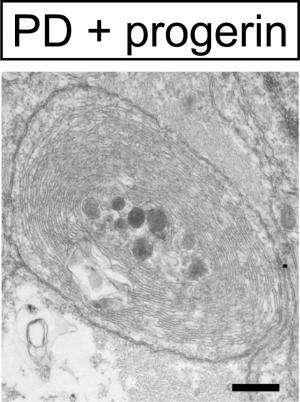

The researchers then used iPSC technology to reprogram skin cells taken from patients with Parkinson's disease and converted the stem cells into the type of neuron that is defective in these patients. After exposure to progerin, these neurons recapitulated disease-related features, including neuronal degeneration and cell death as well as mitochondrial defects.

"We could observe novel disease-related phenotypes that could not be modeled in previous efforts of studying Parkinson's disease in a dish," says first author Justine Miller of the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research. "We hope that the strategy will enable mechanistic studies that could explain why a disease is late-onset. We also think that it could enable a more relevant screening platform to develop new drugs that treat late-onset diseases and prevent degeneration."

More information: Cell Stem Cell, Miller et al.: "Human iPSC-based Modeling of Late-Onset Disease via Progerin-induced Aging." dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.006