Friends in low places preserve gut health

The bacterial communities that live in our intestines should not be considered freeloaders—they contribute substantially to our well-being in a number of ways, including assisting in the breakdown of otherwise indigestible dietary fiber. Hiroshi Ohno from the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences and colleagues have now discovered a mechanism by which this digestive assistance also helps to prevent gut inflammation.

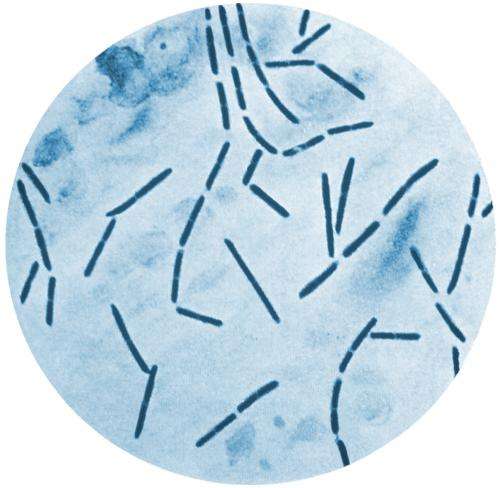

Bacteria belonging to the order Clostridiales are known to metabolize indigestible dietary fiber to produce metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Ohno's team found that mice lacking gut commensal bacteria including Clostridiales exhibit bloating within the cecum—the start of the large intestine—after consuming a high-fiber diet. However, this problem could be repaired by transplanting a Clostridiales-enriched gut bacterial community (Fig. 1).

In other recent work, Ohno and his colleagues demonstrated that these same bacteria stimulate regulatory T (Treg) cells, which specifically prevent the immune system from overreacting. Ohno suspected that this and his most-recent observation might be connected. "This led us to hypothesize that bacterial metabolism of dietary fiber may be the cause of Treg induction," he says.

After searching for metabolic products that were elevated following consumption of a high-fiber diet, the researchers focused on one SCFA, butyrate, as a likely candidate. Butyrate proved capable of converting immature 'naive' T cells into Treg cells in culture, and a maize starch diet that had been chemically enriched with butyrate invoked a similarly potent Treg response within the mouse colon. The same butyrate-enriched maize starch diet failed to elicit Treg proliferation in mice lacking commensal microbes, suggesting that in addition to butyrate, bacterial components are required as an antigen to be recognized by naive T cells.

Butyrate modulates the activity of enzymes that introduce chemical modifications known as 'epigenetic marks' to chromosomes, which can dramatically affect gene expression, and Ohno and his colleagues identified alterations that selectively activate Treg-specific genes. "Bacterial butyrate affected the epigenetic status of naive T cells to propel their differentiation into Treg cells within the colonic tissue," he says. This resulted in a strong protective effect, and the increased numbers of Treg cells that developed following consumption of a butyrate-enriched diet ameliorated inflammation in a mouse model of colitis.

These findings may thus reveal a critical component of the pathology of human inflammatory bowel diseases as well as a potential means for treatment. Ohno and his colleagues now hope to explore whether the same mechanism is also relevant in the inflammatory response to food allergies.

More information: Furusawa, Y., Obata, Y., Fukuda, S., Endo, T. A., Nakato, G., Takahashi, D., Nakanishi, Y., Uetake, C., Kato, K., Kato, T. et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450 (2013). dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12721