'We're all paying:' Heroin spreads misery in US

On a beautiful Sunday last October, Detective Dan Douglas stood in a Minnesota home and looked down at a lifeless 20-year-old—a needle mark in his arm, a syringe in his pocket. It didn't take long for Douglas to realize that the man, fresh out of treatment, was his second heroin overdose that day.

In Ohio, a local rehab facility has a six-month wait. One school recently referred an 11-year-old boy who was shooting up intravenously. Children have been forced into foster care because of addicted parents. Shoplifting rings have formed to raise money to buy fixes.

Heroin is spreading its misery across America. And communities everywhere are paying.

The recent death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman spotlighted the reality that heroin is no longer limited to the back alleys of American life. Once mainly a city phenomenon, the drug has spread—gripping postcard villages in Vermont, middle-class enclaves outside Chicago and other places.

Cocaine, painkillers and tranquilizers are all used more than heroin, and the latest federal overdose statistics show that in 2010 the vast majority of drug overdose deaths involved pharmaceuticals, with heroin accounting for less than 10 percent. But heroin's escalation is troubling. Last month, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder called the 45 percent increase in heroin overdose deaths between 2006 and 2010 an "urgent and growing public health crisis."

In 2007, there were an estimated 373,000 heroin users in the U.S. By 2012, the number was 669,000, with the greatest increases among those 18 to 25. First-time users nearly doubled in a six-year period ending in 2012, from 90,000 to 156,000.

Experts note that many users turned to heroin after a crackdown made prescription drug painkillers such as OxyContin harder to find and more costly. It's killing because it can be extremely pure or laced with other powerful narcotics. That, coupled with a low tolerance once people start using again after treatment, is catching addicts off guard.

IN MINNESOTA: TAKING THE MESSAGE TO THE MASSES

The night before Valentine's Day, some 250 people filed into a church in Minnesota. There were moms and dads of addicts, as well as children whose parents brought them in hopes of scaring them away from the drug.

Dan Douglas gripped a microphone as a photograph appeared overhead on a screen: A woman in the fetal position on a bathroom floor. Then another: A woman passed out with drug paraphernalia near her face.

"You just don't win with heroin," Douglas told the crowd. "You die or you go to jail."

It was the third such forum held over two weeks in Anoka County, home to 335,000 people. Since 1999, 55 residents have died from heroin-related causes. Only one other Minnesota county reported more heroin-related deaths—58—and it has a population three-and-a-half times the county's size.

As prescription drug abuse rose, so, too, did increasing tracking of prescriptions and pharmacy-hopping pill seekers. Users turned to heroin. "It hit us in the face in the form of dead bodies," says Douglas.

IN OHIO: OVERDOSE ANTIDOTE HELPS SAVE SOME

Brakes screech. The hospital door flies open. A panicked voice shouts: "Help my friend!" An unconscious young man, in the throes of a heroin overdose, is lifted onto a gurney.

It's happened repeatedly at Ohio's Fort Hamilton Hospital. The staff's quick response and a dose of naloxone, an opiate-reversing drug, bring most patients back. Some are put on ventilators. A few never revive.

"We've certainly had our share of deaths," says Dr. Marcus Romanello. "At least five died that I am acutely aware of ... because I personally cared for them."

Heroin-related deaths have more than tripled in Butler County, where Hamilton is located. There were 55 deaths last year.

Romanello's hospital saw 200 heroin overdose cases last year. Overdose patients usually bounce back quickly after given naloxone, or Narcan. It works by blocking the brain receptors that opiates latch onto and helping the body "remember" to take in air.

At least 17 states and the District of Columbia allow Narcan to be distributed to the public, and bills are pending in some states to increase access to it. In Ohio, a new law allows a user's friends or relatives to administer Narcan, on condition that they call emergency services.

Romanello says his patients are usually relieved and grateful by the time they leave his hospital. "They say, 'Thank you for saving my life,' and walk out the door. But then, the withdrawal symptoms start to kick in."

IN OREGON: A FORMER ADDICT FIGHTS BACK

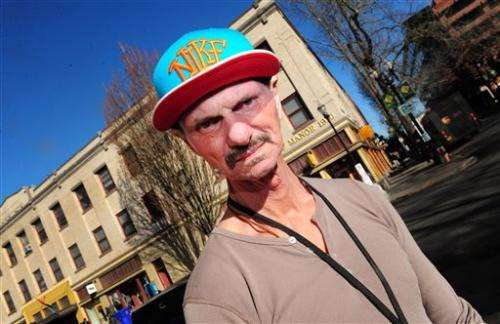

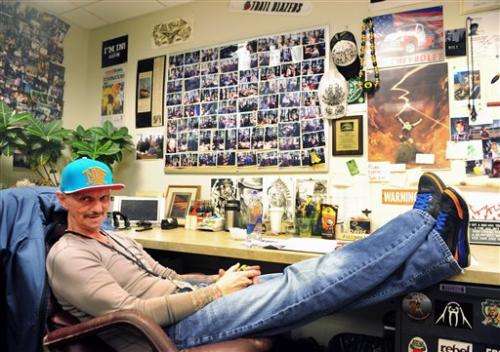

David Fitzgerald is a former addict who leads a mentor program at a rehab clinic in Portland, Oregon.

Heroin cut a gash through the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s. Then prescription pills took over until prices rose. Now the percentage of those in treatment for heroin in Oregon is back up to levels not seen since the '90s—nearly 8,000 people last year—and the addicts are getting younger.

Fitzgerald's clients reflect that. In 2008, 25 percent of them were younger than 35. Last year the number went to 40 percent.

The younger addicts present a new problem—finding appropriately aged mentors to match them with. But Fitzgerald has hope in 26-year-old Felecia Padgett. Before sobriety, Padgett found herself selling heroin to people younger than herself. Using heroin, she says, was like "getting to touch heaven."

Padgett herself is still in recovery. But she, and others like her, may play a crucial role in confronting the problem.

"A lot of them aren't ready at a younger age," Fitzgerald says. "The drug scene, it's fast ... it's different. It's harder than it was."

© 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.