Defect in process that controls gene expression may contribute to Huntington's disease

A protein complex called Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which plays a critical role in forming specific classes of nerve cells in the brain during development, also plays an important role in the adult brain where it may contribute to Huntington's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, according to a study conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published August 15 in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The Mount Sinai study focuses on epigenetics, the study of changes in the action of human genes caused by molecules that regulate when, where, and to what degree our genetic material is activated. Protein complexes have an important role in the biochemical processes that are associated with the expression of genes. Some help to silence genes, whereas others are involved in the activation of genes. The importance of such complexes is emphasized by the fact that mice cannot live if they do not possess PRC2.

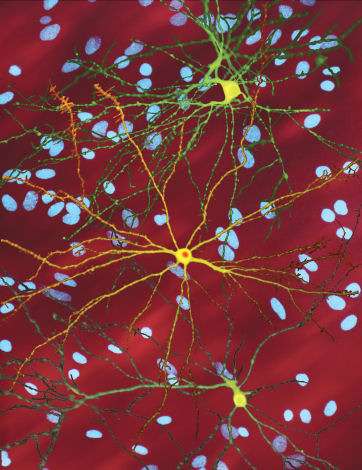

In the striatum, the brain region that regulates voluntary movements, the majority of neurons are called medium spiny neurons (MSNs), so-called because of their spiny appearance. MSNs are further characterized by the expression of a specific set of genes that determines their unique identity and function. Once specified, an MSN's identity needs to be maintained throughout life in order to ensure normal motor function.

PRC2 is an epigenetic gene regulator that represses or silences a given gene's expression. While previous research has found PRC2 to be critical for normal brain development, the role of this protein complex in maintaining the specialization and function of adult MSNs had remained a mystery.

"Normal brain function critically depends on the interaction between highly specialized nerve cells that are specified during early stages of nerve cell development and which remain in place in the adult brain," says Anne Schaefer, PhD, first author on the paper and Associate Professor of Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "Our data establishes, for the first time, that PRC2 not only governs brain cells' development but helps to maintain the MSN identity and function throughout the lifespan of the animal."

To study the role of PRC2 in MSN formation and function, Dr. Schaefer and colleagues generated a mouse model that lacks the PRC2 complex specifically in neurons in the forebrain. The research team found that neurons in mice that lack PRC2, including mice that lacked PRC2 in MSNs, showed inappropriate reactivation of genes that are usually turned off in these cells, and inhibited the expression of genes that are usually turned on and which are essential to the MSN's specific function. The data suggests that PRC2 not only governs the process of brain cell development but also that PRC2 helps to maintain MSNs' identity into the animal's adult life and plays an active role in determining whether the neuron should live or die.

Closer examination of the altered genes in the striatum of the mice that lacked PRC2 revealed that many of these genes controlled by PRC2 are those known to control the process whereby brain cells self-destruct. Consistent with this finding, the PRC2-lacking mice showed signs of progressive cell death in the striatum and had smaller brain mass then non-mutant mice. In addition, these mice developed a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder reminiscent of Huntington's disease in humans, suggesting that disruption of PRC2 may contribute to neurodegenerative disorders.

"One of the remarkable features of the genes controlled by PRC2 is their ability, once activated, to reinforce their own expression," says Dr. Schaefer. "We propose that the PRC2 target genes we identified form collectively into a kind of molecular clock, where the temporal scale of gene activation and subsequent neuron dedifferentiation defines the timing of neuron degeneration."

More information: [39] Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) silences genes responsible for neurodegeneration, nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/nn.4360