Is changing one's race a sign of mental health problems?

Rachel Dolezal was born to white parents and raised as a white child, but privately "transitioned" to a self-identified black woman after attending (and suing) the historically black Howard University. She first made headlines last year when she was outed as white by a local Spokane news reporter. She was in the news again in September for hosting a black hair expo in Dallas.

The state of Dolezal's psychological well-being seemed to be one of the prominent concerns when she first entered the public eye: Who in their right mind would just up and change their race? This person must be experiencing mental problems, right?

There were lots of opinions. Cognitive scientists suggested Rachel's deception could stem from a basic psychological motivation to create the best version of herself. Some suggested that, on the extreme end, the case could represent body dysmorphic disorder, a mental illness described as a preoccupation with a perceived physical flaw.

The conservative right chimed in against calling her crazy, suggesting she recognized that a "profit could be had through participation in the race industry and its various scams."

However, social scientists may have an alternative explanation for Dolezal's transition. The explanation stems from the idea that race is a social construction, meaning that racial categories are invented categories, often based on how we look or by ancestry, and that they are shaped by society and history.

For instance, who qualifies as black today in the United States is different than who would qualify as black in the 19th century. The socially constructed nature of race not only means that society's conception of race changes over time, but that individuals might change how they themselves identify over time.

As a sociologist, I have sought to understand how individuals identify themselves racially, and whether there are consequences to having changing racial identifications, or what is called racial fluidity.

Racial identification fluidity over time

According to a report that came out of the 2010 census, 9.8 million Americans changed their racial identification since the 2000 census. While it still remains rare for a white person to change his or her race to black, some racial groups have extremely high rates of change.

For instance, the rate of change over the 10-year period reached almost 50 percent for American Indians and Pacific Islanders. Elizabeth Warren stands out as an example of a high-profile person who has identified as American Indian inconsistently in her lifetime.

Scholars have formulated various explanations for why people change racial identifications. Sociologists Saperstein and Penner break it down into three main reasons: They are following classification norms; they seek to achieve higher prestige or move away from negative connotations; and/or because they have a wide range of available classifications to choose from.

What remains unanswered, however, is whether there are psychological consequences to racial fluidity.

In a research study released this fall, my colleague Tony N. Brown, associate professor at Rice University, and I sought to answer that. We first tracked changes in racial identification among a large, nationally representative sample of adolescents at two points in time.

We then questioned whether changes to self racial-identification was detrimental to mental well-being. We were additionally curious whether changes to observed racial identification were also detrimental.

American Indians in sample showed high fluidity

The survey we analyzed allowed the youth respondents to identify their own race and also asked the interviewers to make a judgment of the respondents' race. We looked at whether changes to race, by either the respondent (self) or interviewer (observer), were related to poor mental health.

Given the high proportion of racial fluidity among American Indians, we conducted this analysis on the subsample of youth who were identified, either by the self or observer, as American Indian.

We first calculated how many experienced racial fluidity. We found that 79 percent of the respondents expressed an inconsistent self-identification as American Indian. That is, of all of the youths who said they were American Indian at either rounds of the survey, only 21 percent said they were American Indian at both rounds.

Likewise, 77 percent were inconsistently observed as American Indian. So, of all the youth judged to be American Indian by the interviewers, only 23 percent were thought to be American Indian at both rounds.

In short, rates of racial identification fluidity – by self or interviewer – were high among American Indian respondents. As a comparison point, rates of fluidity for blacks and whites in the sample fell below 5 percent.

Is changing your own race associated with poor mental health?

We next used those measures of racial identification fluidity to predict mental health status – measured in our study as depressive symptoms, thinking about or contemplating suicide, and use of psychological counseling. Our analysis also controlled for basic social demographic factors, like socioeconomic status and skin color.

The unexpected answer to our first question was no: Changing one's stated race over time had no association with poor mental health.

When we returned to the explanations for racial identification change, our findings began to make more sense. Deciding to adopt the category of American Indian could represent a newfound familial heritage. Alternatively, opting to drop the category could be a choice to avoid stigma associated with being a member of a group that has faced discrimination.

More broadly, though, "trying on" different racial identifications may be a normal process, especially during adolescence. We concluded that fluidity in expressed racial identification does not represent a weak or troubled sense of self. Instead, fluidity represents control over their identity.

Are changing perceptions of your race by others associated with poor mental health?

In contrast, the answer to our second question was yes: Changes to one's perceived racial identification did damage mental health status. That is, when an interviewer observed a respondent as American Indian at one time but not the other, that respondent had an increased risk for mental health problems.

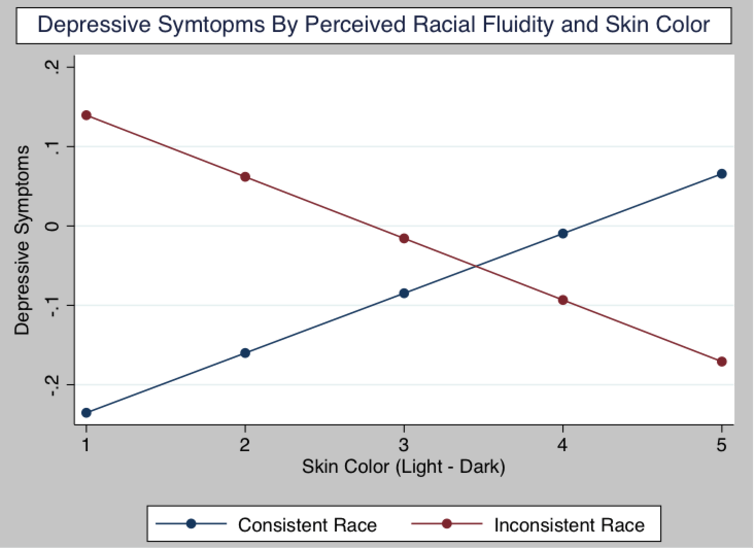

In addition, when those who were observed inconsistently also had lighter skin, the psychological problems were heightened. As the figure illustrates, falling into the light end of the skin color spectrum, and having observers inconsistently perceive your race, is associated with the highest number of depressive symptoms.

We turned to social psychology for an answer to this surprising finding. According to identity change theory, lack of control of one's identity can be detrimental to psychological health. A person can become aware of their lack of control through the experience of an identity interruption. An example of a racial identity interruption could be the "What are you?" question that many light skin and racially ambiguous folks often encounter.

We reason that fielding queries about one's race – or even perceiving others to be confused about your race – may cause distress. While other sociologists have found that misclassification of one's race by others is harmful to mental health, our findings lead us to conclude that people who are assigned inconsistent racial identifications by others may suffer as a result.

In regards to Dolezal, well, she continues to stand out as an odd case – none of the explanations typically applied to racial fluidity truly work for her. She is not an adolescent trying on different identities. She opted out a privileged racial category and into a category that is confronted with ample discrimination in terms of jobs, housing and health.

Perhaps she did face identity interruptions and was often asked, "What are you?," particularly when she positioned herself in majority black surroundings. This could have even motivated her racial transition.

But what does this all mean for her mental well-being? While that is still unclear, this research does suggest that our fixation with other's race can, indeed, be harmful.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()