Overnutrition in the Western world has led to an epidemic of type 2 diabetes. Credit: Peter Allen, University of California, Santa Barbara

Newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics tend to have one thing in common: obesity. Exactly how diet and obesity trigger diabetes has long been the subject of intense scientific research. A new study led by Jamey D. Marth, Ph.D., director of the Center for Nanomedicine, a collaboration between the University of California, Santa Barbara and Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham), has revealed a pathway that links high-fat diets to a sequence of molecular events responsible for the onset and severity of diabetes. These findings were published online August 14 in Nature Medicine.

In studies spanning mice and humans, Dr. Marth's team discovered a pathway to disease that is activated in pancreatic beta cells, and then leads to metabolic defects in other organs and tissues, including the liver, muscle and adipose (fat). Together, this adds up to diabetes.

"We were initially surprised to learn how much the pancreatic beta cell contributes to the onset and severity of diabetes," said Dr. Marth."The observation that beta cell malfunction significantly contributes to multiple disease signs, including insulin resistance, was unexpected. We noted, however, that studies from other laboratories published over the past few decades had alluded to this possibility."

In healthy people, pancreatic beta cells monitor the bloodstream for glucose using glucose transporters anchored in their cellular membranes. When blood glucose is high, such as after a meal, beta cells take in this additional glucose and respond by secreting insulin in a timed and measured response. In turn, insulin stimulates other cells in the body to take up glucose, a nutrient they need to produce energy.

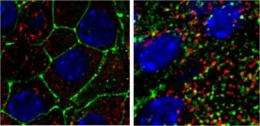

High-fat diet and obesity cause beta cells to lose their ability to sense glucose in the blood. Left: Pancreatic beta cells from a mouse on a standard diet. Right: Pancreatic beta cells from a mouse fed a high-fat diet. (green=glucose transporters, red=insulin, blue=DNA) Credit: Marth laboratory, Sanford-Burnham/UCSB

In this newly discovered pathway, high levels of fat were found to interfere with two key transcription factors—proteins that switch genes on and off. These transcription factors, FOXA2 and HNF1A, are normally required for the production of an enzyme called GnT-4a glycosyltransferase that modifies proteins with a particular glycan (polysaccharide or sugar) structure. Proper retention of glucose transporters in the cell membrane depends on this modification, but when FOXA2 and HNF1A aren't working properly, GnT-4a's function is greatly diminished. So when the researchers fed otherwise normal mice a high-fat diet, they found that the animals' beta cells could not sense and respond to blood glucose. Preservation of GnT-4a function was able to block the onset of diabetes, even in obese animals. Diminished glucose sensing by beta cells was shown to be an important determinant of disease onset and severity.

"Now that we know more fully how states of over-nutrition can lead to type 2 diabetes, we can see more clearly how to intervene," Dr. Marth said. He and his colleagues are now considering various methods to augment beta cell GnT-4a enzyme activity in humans, as a means to prevent and possibly cure type 2 diabetes.

"The identification of the molecular players in this pathway to diabetes suggests new therapeutic targets and approaches towards developing an effective preventative or perhaps curative treatment," Dr. Marth continued. "This may be accomplished by beta cell gene therapy or by drugs that interfere with this pathway in order to maintain normal beta cell function."

Provided by Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute