Engineered microvessels provide a 3-D test bed for human diseases

Mice and monkeys don't develop diseases in the same way that humans do. Nevertheless, after medical researchers have studied human cells in a Petri dish, they have little choice but to move on to study mice and primates.

University of Washington bioengineers have developed the first structure to grow small human blood vessels, creating a 3-D test bed that offers a better way to study disease, test drugs and perhaps someday grow human tissues for transplant.

The findings are published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"In clinical research you just draw a blood sample," said first author Ying Zheng, a UW research assistant professor of bioengineering. "But with this, we can really dissect what happens at the interface between the blood and the tissue. We can start to look at how these diseases start to progress and develop efficient therapies."

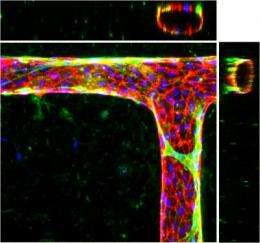

Zheng first built the structure out of the body's most abundant protein, collagen, while working as a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University. She created tiny channels and injected this honeycomb with human endothelial cells, which line human blood vessels.

During a period of two weeks, the endothelial cells grew throughout the structure and formed tubes through the mold's rectangular channels, just as they do in the human body.

When brain cells were injected into the surrounding gel, the cells released chemicals that prompted the engineered vessels to sprout new branches, extending the network. A similar system could supply blood to engineered tissue before transplant into the body.

After joining the UW last year, Zheng collaborated with the Puget Sound Blood Center to see how this research platform would work to transport real blood.

The engineered vessels could transport human blood smoothly, even around corners. And when treated with an inflammatory compound the vessels developed clots, similar to what real vessels do when they become inflamed.

The system also shows promise as a model for tumor progression. Cancer begins as a hard tumor but secretes chemicals that cause nearby vessels to bulge and then sprout. Eventually tumor cells use these blood vessels to penetrate the bloodstream and colonize new parts of the body.

When the researchers added to their system a signaling protein for vessel growth that's overabundant in cancer and other diseases, new blood vessels sprouted from the originals. These new vessels were leaky, just as they are in human cancers.

"With this system we can dissect out each component or we can put them together to look at a complex problem. That's a nice thing—we can isolate the biophysical, biochemical or cellular components. How do endothelial cells respond to blood flow or to different chemicals, how do the endothelial cells interact with their surroundings, and how do these interactions affect the vessels' barrier function? We have a lot of degrees of freedom," Zheng said.

The system could also be used to study malaria, which becomes fatal when diseased blood cells stick to the vessel walls and block small openings, cutting off blood supply to the brain, placenta or other vital organs.

"I think this is a tremendous system for studying how blood clots form on vessels walls, how the vessel responds to shear stress and other mechanical and chemical factors, and for studying the many diseases that affect small blood vessels," said co-author Dr. José López, a professor of biochemistry and hematology at UW Medicine and chief scientific officer at the Puget Sound Blood Center.

Future work will use the system to further explore blood vessel interactions that involve inflammation and clotting. Zheng is also pursuing tissue engineering as a member of the UW's Center for Cardiovascular Biology and the Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine.

More information: “In vitro microvessels for the study of angiogenesis and thrombosis," by Ying Zheng et al. PNAS, 2012.