Army, academia develop human-on-a-chip technology

There was a time when the thought of manufacturing organs in the laboratory was science fiction, but now that science is a reality. Army Scientists at the Edgewood Chemical Biological Center and academia collaborators have been conducting research of "organs" on microchips. ECBC is one of a few laboratories in the world conducting this research effort, but what sets ECBC apart is that its research will directly impact the warfighter.

The center houses the only laboratories in the United States that the Chemical Weapons Convention permits to produce chemical warfare agent for testing purposes. ECBC will test the human-on-a-chip against chemical warfare agent to learn more about how the body will respond to agent exposure and explore various treatment options for exposures.

While the center will be collaborating with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense, Wake Forest, Harvard and the University of Michigan on the design of the chip, the testing will take place at ECBC.

The five-year research project is being funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and will focus on a platform of in vitro human organ constructs in communication with each other. This platform will assess effectiveness and toxicity of drugs in a way that is relevant to humans' and their ability to process these drugs.

ECBC scientists were already undergoing research on four organs—the heart, liver, lung and the nervous system—when DTRA solicited a call for proposals. Then once the proposal was awarded, the center began working specifically on the heart, liver, lung and the circulatory system. Dr. Harry Salem, ECBC's chief scientist for Life Sciences, leads ECBC's in vitro research team working with stem cells.

"Stem cells are a relatively new field of research," Salem said. "The stem cells that ECBC uses … are made from adult skin cells called induced pluripotent stem cells."

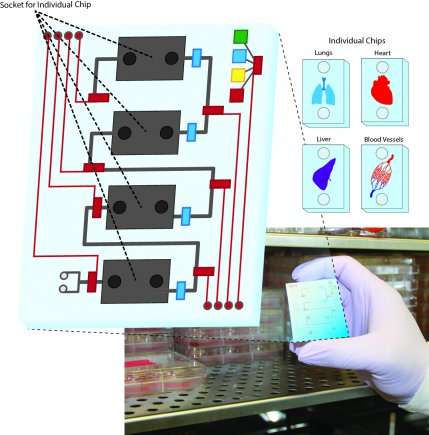

Each organ-on-a-chip is about the size of a thumb drive and is an organoid, or a small swatch of human tissue, designed to mimic the properties of an actual human organ. They are made up of multiple layers of cells growing on a membrane and are connected to each other by microfluidics, tiny micro channels that copy the function of blood vessels. Their primary purpose is to take the place of animal research.

"Today, the use of stem cells in our research program is moving us toward that goal," Salem said. "Here at ECBC, the screening models will be used to assess the efficacy and safety of medical mitigation procedures and counter measures for the soldier and the nation as a whole."

According to Salem, compounds quite often behave differently in people than they do in animals. For that reason human estimate studies are used, but do not always accurately reflect the human response. Due to the species-specific differences by which compounds are metabolized, a drug tested on a laboratory rat doesn't always translate well to a human. In some cases, no animal testing can mimic the human response. Asthma, for example, is a uniquely human disease. Since human-on-a-chip is made from human cells, it is the next best thing. Human tissue reacts like human tissue.

It is anticipated that new predictive models of toxicity will result from the more accurate human-on-a-chip testing. This will save both time and money. Pharmaceuticals tested on animals fail to work on humans 90 percent of the time. This technology will result in fewer test failures. Scientists will be able to narrow their research efforts by identifying which therapeutics will be effective or fail early on in the testing process.

"The human-on-a-chip promises to accelerate the pace of research and consequently scientific breakthroughs," Dr. Russell Dorsey, a research microbiologist and one of the members performing the in vitro testing at ECBC, said. "For the military, our human-on-a-chip research will save actual warfighters' lives."