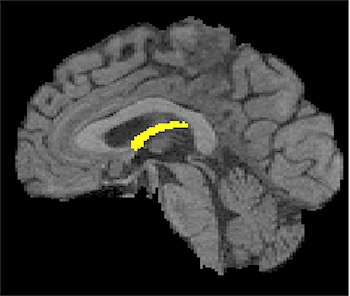

This image of a brain shows the fornix structure highlighted. Credit: UC Davis

The degeneration of a small, wishbone-shaped structure deep inside the brain may provide the earliest clues to future cognitive decline, long before healthy older people exhibit clinical symptoms of memory loss or dementia, a study by researchers with the UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Center has found.

The longitudinal study found that the only discernible brain differences between normal people who later developed cognitive impairment and those who did not were changes in their fornix, an organ that carries messages to and from the hippocampus, and that has long been known to play a role in memory.

"This could be a very early and useful marker for future incipient decline," said Evan Fletcher, the study's lead author and a project scientist with the UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Center.

"Our results suggest that fornix variables are measurable brain factors that precede the earliest clinically relevant deterioration of cognitive function among cognitively normal elderly individuals," Fletcher said.

The research is published online today in JAMA Neurology.

Hippocampal atrophy occurs in the later stages of cognitive decline and is one of the most studied changes associated with the Alzheimer's disease process. However, changes to the fornix and other regions of the brain structurally connected to the hippocampus have not been as closely examined. The study found that degeneration of the fornix in relation to cognition was detectable even earlier than changes in the hippocampus.

"Although hippocampal measures have been studied much more deeply in relation to cognitive decline, our direct comparison between fornix and hippocampus measures suggests that fornix properties have a superior ability to identify incipient cognitive decline among healthy individuals," Fletcher said.

The study was conducted over five years in a group of 102 diverse, cognitively normal people with an average age of 73 who were recruited through community outreach at the Alzheimer's Disease Center. The researchers conducted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the participants' brains that described their volumes and integrity. A different type of MRI was used to determine the integrity of the myelin, the fatty coating that sheaths and protects the axons. The axons are analogous to the copper wiring of the brain's circuitry and the myelin is like the wiring's plastic insulation.

Either one of those things being lost will "degrade the signal transmission" in the brain, Fletcher said.

The researchers also conducted psychological tests and cognitive evaluations of the study participants to gauge their level of cognitive functioning. The participants returned for updated MRIs and cognitive testing at approximately one-year intervals. At the outset, none of the study participants exhibited symptoms of cognitive decline. Over time about 20 percent began to show symptoms that led to diagnoses with either mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and, in a minority of cases, Alzheimer's disease.

"We found that if you looked at various brain factors there was one—and only one—that seemed to be predictive of whether a person would have cognitive decline, and that was the degradation of the fornix," Fletcher said.

The study measured two relevant fornix characteristics predicting future cognitive impairment—low fornix white matter volume and reduced axonal integrity. Each of these was stronger than any other brain factor in models predicting cognitive loss, Fletcher said.

He said that routine MRI examination of the fornix could conceivably be used clinically in the future as a predictor of abnormal cognitive decline.

"Our findings suggest that if your fornix volume or integrity is within a certain range you're at an increased risk of cognitive impairment down the road. But developing the use of the fornix as a predictor in a clinical setting will take some time, in the same way that it took time for evaluation of cholesterol levels to be used to predict future heart disease," he said.

Fletcher also said that the finding may mark a paradigm shift toward evaluation of the brain's white matter, rather than its gray matter, as among the very earliest indicators of developing cognitive loss. There is currently a strong research focus on understanding brain processes that lead eventually to Alzheimer's disease. He said the current finding could fill in one piece of the picture and motivate new directions in research to understand why and how fornix and other white matter change is such an important harbinger of cognitive impairment.

"The key importance of this finding is that it suggests that white matter tract measures may prove to be promising candidate biomarkers for predicting incipient cognitive decline among cognitively normal individuals in a clinical setting, possibly more so than gray matter measures," he said.

More information: JAMA Neurol. Published online September 9, 2013. doi:10.1001/.jamaneurol.2013.3263

Journal information: Archives of Neurology

Provided by UC Davis