Patients receiving free or low-cost medications may not stick to their prescription perfectly, but they're not much different than patients with insurance, according to a study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The study, led by Drew Roberts, a Ph.D. candidate at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, suggests that providing medications to people who cannot afford them may not only improve medication use but also decrease health care costs and improve the health of Americans, especially in low-income and underserved communities.

"Low-income patients who have chronic diseases but not insurance have a difficult time getting medications reliably, which often leads to serious, unnecessary and costly health problems," said Roberts, whose work appears in the North Carolina Medical Journal.

From 2009 to 2011, UNC researchers studied patients enrolled in the UNC Health Care Pharmacy Assistance Program, or PAP, which provides free or reduced-cost medication to low-income patients. The patients received medication for high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol and their medication use was monitored over six months.

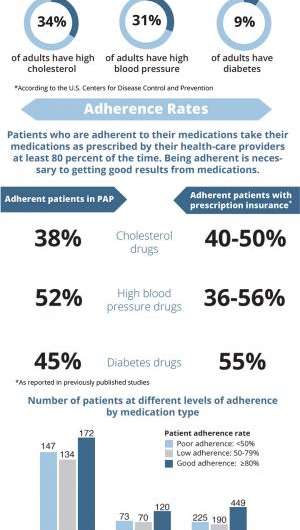

In North Carolina, approximately nine percent of adults have diabetes, 31 percent have high blood pressure and about 34 percent have high cholesterol, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The diseases are some of the most costly conditions in the United States.

The study set the bar for optimal adherence at 80 percent, meaning patients took their medications as directed by their health care providers 80 percent of the time. About half the patients in the study taking medications for the three chronic conditions hit the 80 percent adherent mark – adherence rates that are comparable to patients with prescription insurance.

The percentage of people who were adherent for the three conditions were:

- 38 percent taking medication for high cholesterol (compared to 40 to 50 percent of patients with insurance)

- 52 percent taking medication for high blood pressure (compared to 36 to 56 percent of patients with insurance)

- 45 percent taking medication for diabetes (compared to 55 percent of patients with insurance)

The study also found that PAP patients who took their medications as prescribed were more likely to be older, more likely to be white and more likely to be taking multiple prescriptions.

Co-author Ginny Crisp, a pharmacist at UNC Hospitals and an assistant professor at the pharmacy school, said the study will not only guide the operation of UNC's assistance program, it will also be valuable to others.

"This study provides valuable evidence for administrators of similar charitable pharmacy assistance programs in other states serving large numbers of uninsured patients, primarily states that have opted out of expanding Medicaid eligibility under health reform," Crisp said.

"We have also identified clear opportunities to improve the pharmacy care here at UNC-Chapel Hill by increasing medication adherence of PAP participants and improving the care they receive."

More information: "Patterns of Medication Adherence and Health Care Utilization Among Patients With Chronic Disease Who Were Enrolled in a Pharmacy Assistance Program": www.ncmedicaljournal.com/archives/?75502

Provided by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill