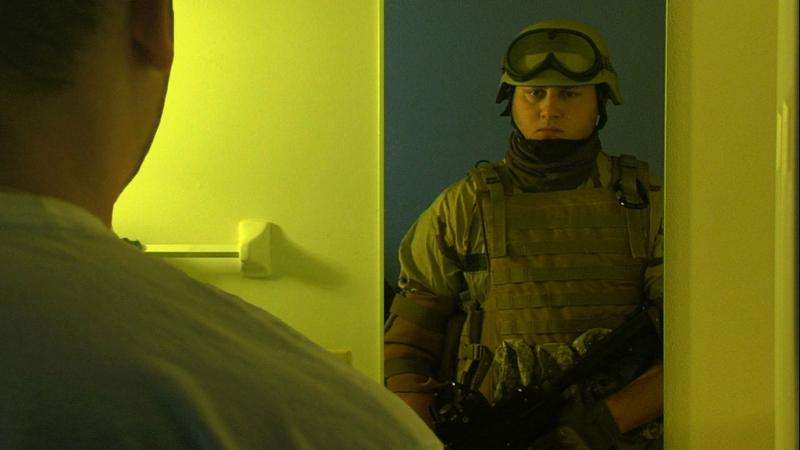

Soldiers who suffer from PTSD may literally see a world more populated with reminders of trauma, thereby perpetuating its effects, says the study’s lead author. Credit: Peter Murphy/Flickr

Soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may see a world more full of threat than those not suffering from the affliction, according to a study led by UBC and The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto.

The findings underline how PTSD – a trauma-related mental disorder linked to higher levels of emotional arousal and anxiety – influences the way the human brain views its environment.

"Soldiers who suffer from PTSD may literally see a world more populated with reminders of trauma, thereby perpetuating its effects," said Rebecca Todd, the study's lead author and an assistant professor in UBC's department of psychology.

The study, published in Biological Psychiatry, involved a group of Canadian Armed Forces soldiers: half with PTSD, half without, and all on active duty. Each soldier was placed inside a MEG (magnetoencephalography) scanner, a neuroimaging device that tracks how rapidly brain functions occur.

The soldiers then viewed a rapid stream of 15 words, most of which were neutral and in black font. However, two of the so-called targets appeared in green font: the first was a number, and the second was either a neutral or a combat-related word, such as convoy, medic or deploy.

Soldiers were asked to report the two targets. Typically, when the second target appears too soon after the first, it is simply missed. "It's as if the mind blinks," said Todd. "We think we see everything in our environment, but we don't. Our brains are very good filters."

But when the second target is emotionally relevant to the subject, it is also more likely to be seen, an outcome supported by the study. While all soldiers showed a bias for combat-related words, this bias was more pronounced for the PTSD group. That group also displayed distinct patterns of brain activity and reported higher levels of emotional arousal for combat-related words.

"Soldiers with combat experience are more likely to see aspects of the environment that are associated with combat than civilians," said Todd. "This effect is stronger in soldiers with PTSD than in those without."

"This study adds to a growing literature suggesting there is a direct link between brain processes and PTSD symptoms," says Dr. Elizabeth Pang, senior author of the paper and a neurophysiologist and associate scientist at SickKids.

Background

The study, "Soldiers with PTSD see a world full of threat: MEG reveals enhanced tuning to combat-related cues," is published in Biological Psychiatry. It involved 44 soldiers from the Canadian Armed Forces – 22 with PTSD, and 22 without. Before entering the MEG (magnetoencephalography) scanner, participants performed a practice version of the task using only neutral words. Once inside the MEG scanner, they were presented with 15 stimuli, which were each presented for a tenth of a second in rapid succession. Responses to target numbers and words were recorded as either "hits" (accurate) or "misses" (inaccurate); corresponding brain activity was analyzed to understand the neural processes.

More information: "Soldiers with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder See a World Full of Threat: Magnetoencephalography Reveals Enhanced Tuning to Combat-Related Cues." DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.011

Journal information: Biological Psychiatry

Provided by University of British Columbia