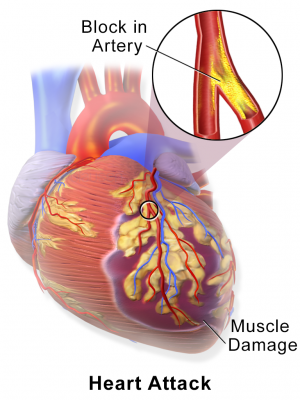

Myocardial Infarction or Heart Attack. Credit: Blausen Medical Communications/Wikipedia/CC-A 3.0

Young women who survive a heart attack or stroke still face long-term risks of death and illness, according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

While death rates from the acute phase of cardiovascular events have decreased, the disease burden remains high in the increasing number of survivors, which is especially important for those affected at a young age. But little information is available about the long-term outcomes of young patients, especially women, who survive cardiovascular events.

Frits R. Rosendaal, M.D., Ph.D., of Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and coauthors determined long-term mortality and morbidity in young women who survived myocardial infarction (heart attack) or ischemic stroke compared with a control group.

The study included 226 women who had a heart attack (average age 42), 160 women who had ischemic stroke (average age 40) and 782 women (average age 48) in the comparison group with no history of arterial thrombosis (blood clot in an artery). The women were followed up for a median of nearly 19 years.

Death rates were 3.7 times higher in women who had a heart attack (8.8 per 1,000 person-years) and 1.8 times higher in women who had ischemic stroke (4.4 per 1,000 person-years) than the comparison patients (2.4 per 1,000 person-years), the authors report. This elevated mortality lasted over time and was mainly supported by a high rate of deaths from acute vascular events.

When both fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events were counted, the incidence rate was highest in women who had an ischemic stroke (14.1 per 1,000 person-years) compared with the control group. The rate was 12.1 per 1,000 person-years in women who had a heart attack, the results indicate.

In women who had a heart attack, the risk of cardiac events was 10.1 per 1,000 person-years and the risk of cerebral events was 1.9 per 1,000 person-years. In women who had an ischemic stroke, the risk of cerebral events was 11.1 per 1,000 person-years and the risk of cardiac events was 2.7 per 1,000 person-years.

The authors acknowledge a reduced generalizability of their results because procedures and risk factors change over time, which is a problem of all long-term follow-up studies.

"Our findings provide direct insight into the consequences of cardiovascular diseases in young women, which persist for decades after the initial event, stressing the importance of life-long prevention strategies," the authors conclude.

More information: JAMA Intern Med. Published online November 23, 2015. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6523

Journal information: JAMA Internal Medicine

Provided by The JAMA Network Journals