Psychology's meta-analysis problem

Psychology has a meta-analysis problem. And that's contributing to its reproducibility problem. Meta-analyses are wallpapering over many research weaknesses, instead of being used to systematically pinpoint them.

It's a bit of a case of a prophet not being recognized in its hometown. Meta-analysis was born in the late 1970s in educational psychology. It's the process of combining and analyzing data from more than one study at a time (more here).

Pretty soon, medical researchers realized it could be "a key element in improving individual research efforts and their reporting". They forked off down the path of embedding meta-analysis in systematic reviewing – so much so, that many people mistake "meta-analysis" and "systematic review" as synonyms.

But they're not. Systematic reviewing doesn't just gather and crunch numbers from multiple studies. The process should include systematic critical assessment of the quality of study design and risk of bias in the data as well. Unreliable study results can fatally tilt results in a meta-analysis in misleading directions.

And psychology research can have a very high risk of bias. For example, many areas of psychology research are particularly prone to bias because of their populations: often volunteers rather than a sample selected to reduce bias, college students, or drawn from the internet or Mechanical Turk. They tend to be, as Joseph Henrich and colleagues pointed out [PDF], "the weirdest people in the world": from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. And their responses may not be reliable enough, either.

Here's an example of what this means for a body of studies. I looked at this meta-analysis on changing implicit bias when l was researching for a recent blog post. It sounds like a solid base from which to draw conclusions: 427 studies with 63,478 participants.

But 84% of the participants are college students, 66% female, and 55% from the USA. They're nearly all very short-term studies (95%), 85% had no measures of behavior in them, and 87% had no pre-test results.

James Coyne recently walked through a range of other critical biases and "questionable research practices" (QRPs) affecting the literature in psychology, including selective reporting of analyses, studies that are too small and lack scientific rigor, over-reliance on statistical significance testing, and investigator allegiance to a therapy or idea. John Ioannidis and colleagues (2014) also document extensive over-reporting of positive results and other reporting biases across the cognitive sciences.

Coyne and colleagues found that these problems were bleeding through into a group of meta-analyses they studied, too [PDF]. Christopher Ferguson and Michael Brannick suspected a skew from unpublished studies in 20-40% of the psychology meta-analyses they studied [PDF]. Michiel van Elk and his colleagues found similar problems, pointing out

f there is a true effect, then a meta-analysis will pick it up. But a meta-analysis will also indicate the existence of an effect if there is no true effect but only experimenter bias and QRPs.

Guy Cafri, Jeffrey Kromrey and Michael Brannick add to this list a range of problems of statistical rigor in meta-analyses published across a decade in a major psychology journal – including multiple testing (an explainer here).

It's not that these problems don't exist in meta-analysis in other fields. But the problem seems far more severe in psychology, largely, it seems to me, because of the way meta-analysis has evolved in this field. In clinical research, systematic reviewing started to make these problems clear in the 1970s and 1980s – and the community started chipping away at them.

Formal instruments for assessing the robustness and risk of bias of different study types were developed and evaluated, and those assessments were incorporated into systematic reviews. We called what drove this process "methodology research". John Ioannidis and his team at METRICS call it meta-research:

Meta-research is an evolving scientific discipline that aims to evaluate and improve research practices.

It's a long way from being a perfect science itself. It's not that easy to reliably measure the reliability of data! And it's not implemented as fully as it should be in clinical systematic reviews either. But it is the expected standard. (See for example PRISMA and AMSTAR for systematic reviews, and Julian Higgins and colleagues for meta-analyses [PDF].) Two of the key features of systematic reviews are appraising the quality of the evidence and minimizing bias within the review process itself.

Yet, in the equivalent for psychology – Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS) – assessment of data quality is optional. Gulp.

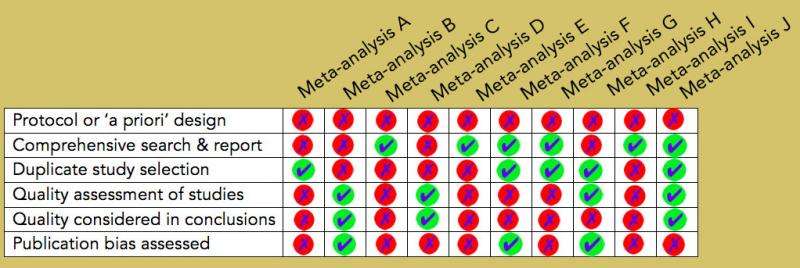

Fortunately, in psychological therapies, many adhere to clinical research standards for systematic reviews. To test my impressions of how non-therapeutic, non-imaging meta-analyses in psychology stack up, I assessed 10 published in the psychological literature in June on some key criteria. (Details of how I got to this 10 are at the foot of this post. And for comparison with biomedical systematic reviews, I used the recent study by Matthew Page and colleagues.)

It's a small group of psychology meta-analyses, and I'm the only person who did the assessment, which are 2 big sources of bias. I tried to be very generous. It still isn't a pretty picture – only 1 out of 10 meta-analyses came out with more thumbs up than down ("J"). And this was only a subset of quality criteria for a systematic review.

None reported a protocol or 'a priori' design for the meta-analysis. That's explicitly reported in about 40% of systematic reviews in biomedical research. The rate of comprehensive search for studies, with detail reported, was 60% (compared with around 90% for biomedicine). And the key issues of quality assessment? Half as often for psychology: only 30 and 40%, compared with 60 and 80% in biomedicine.

The risk of bias in the studies meta-analyzed was mostly unquestioned. Perhaps more of the authors share the misassumption of authors of "A":

48.9% of the studies in this dataset (i.e. 68 out of 139 published articles) come from the six leading SCM journals mentioned above, and 77.7% of the papers (i.e. 108 out of 139) are published in journals included in the master list of the Social Sciences Citation Index. Therefore, the quality of the studies that provide the correlations for this meta-analysis is considered high. A list of the studies is available on request.

Oh boy. Perhaps people would have less faith in the published literature in their discipline if they really looked under the hood.

When I was looking for research tools to evaluate risk of bias in psychology studies, I found an article with the promising title, "Evaluating psychological reports: dimensions, reliability, and correlates of quality judgments". But this 1978 article turned out to be instructive for other reasons. It was based on what editors and consultants for 9 major psychology journals thought was worth publishing. It rather meticulously describes the foundations on which psychology's replication crisis was built:

Component VI seems primarily to reflect scientific advancement, while Component VII seems to merit the label "data grinders" or "brute empiricism," with emphasis on description rather than explanation. The eighth component might be labeled "routine" or "ho-hum" research and brings to mind the remark one respondent penciled in the questionnaire margin: "How about an item like, 'Oh God, there goes old so-and-so again!' ?"

The derided components VII and VIII include bedrocks of good science, like "The author uses precisely the same procedures as everyone else", and "The results are not overwhelming in their implications, but they constitute a needed component of knowledge". You can see what this publication culture led to in a great example Neuroskeptic explained: romantic priming. Or another case – including problematic meta-analysis – Daniel Engber wrote about: self-control and ego depletion.

Meta-research is well on its way in psychology and neuroscience, and pointing to lots of ways forward. Kate Button and colleagues show the importance of increasing sample sizes, Chris Chambers and more than 80 colleagues call for study pre-registration.

Changing the expectations of meta-analysis in psychology needs to be part of the new direction, too. Meta-analysis began in psychology. But long experience is no guarantee of being on the right track. Oscar Wilde summed that up in 1890 in The Picture of Dorian Gray:

He began to wonder whether we could ever make psychology so absolute a science that each little spring of life would be revealed to us. As it was, we always misunderstood ourselves and rarely understood others. Experience was of no ethical value. It was merely the name men gave to their mistakes…All that it really demonstrated was that our future would be the same as our past.

More information: Elizabeth A. Necka et al. Measuring the Prevalence of Problematic Respondent Behaviors among MTurk, Campus, and Community Participants, PLOS ONE (2016). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157732

James C. Coyne. Replication initiatives will not salvage the trustworthiness of psychology, BMC Psychology (2016). DOI: 10.1186/s40359-016-0134-3

Guy Cafri et al. A Meta-Meta-Analysis: Empirical Review of Statistical Power, Type I Error Rates, Effect Sizes, and Model Selection of Meta-Analyses Published in Psychology, Multivariate Behavioral Research (2010). DOI: 10.1080/00273171003680187

This story is republished courtesy of PLOS Blogs: blogs.plos.org.