Research opens possibility of reducing risk of gut bacterial infections with next-generation probiotics

A team of researchers is exploring the possibility that next-generation probiotics – live bacteria that are good for your health – would reduce the risk of infection with the bacterium Clostridium difficile. In laboratory-grown bacterial communities, the researchers determined that, when supplied with glycerol, the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri produced reuterin, an antibacterial compound that selectively killed C. difficile. The study appears in Infection and Immunity.

"C. difficile causes thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in healthcare expenses in the U.S. each year. Although most patients respond to antibiotic treatment, up to 35 percent will relapse and require extended antibiotic treatments," said first and corresponding author Dr. Jennifer K. Spinler, instructor of pathology & immunology at Baylor College of Medicine, who oversees microbial genetics and genomics efforts at the Texas Children's Microbiome Center at Texas Children's Hospital.

C. difficile infections are the most common cause of diarrhea associated with the use of antibiotics. If these bacteria attempt to invade the human gut, the 'good bacteria,' which outnumber C. difficile, usually prevent them from growing. However, when a person takes antibiotics, for example to treat pneumonia, the antibiotic also can kill the good bacteria in the gut, opening an opportunity for C. difficile to thrive into a potentially life-threatening infection.

"When repeated antibiotic treatments fail to eliminate C. difficile infections, some patients are resorting to fecal microbiome transplant – the transfer of fecal matter from a healthy donor – which treats the disease but also could have negative side effects," Spinler said. "We wanted to find an alternative treatment, a prophylactic strategy based on probiotics that could help prevent C. difficile from thriving in the first place."

"Probiotics are commonly used to treat a range of human diseases, yet clinical studies are generally fraught by variable clinical outcomes and protective mechanisms are poorly understood in patients. This study provides important clues on why clinical efficacy may be seen in some patients treated with one probiotic bacterium but not with others," said senior author Dr. Tor Savidge, associate professor of pathology & immunology and of pediatrics at Baylor and the Texas Children's Microbiome Center.

Working in the Texas Children's Microbiome Center, Spinler and her colleagues tested the possibility that probiotic L. reuteri, which is known to produce antibacterial compounds, could help prevent C. difficile from establishing a microbial community in lab cultures.

An unexpected result with major implications for a preventative strategy

Spinler and Savidge established a collaboration with co-author Dr. Robert A. Britton, professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor and member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

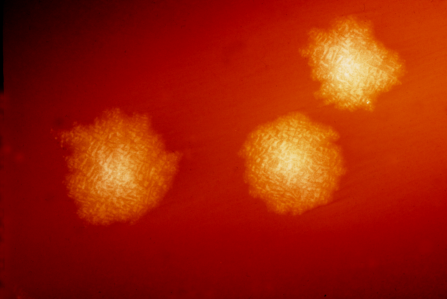

The Britton lab uses mini-bioreactor arrays – multiple small culture chambers – that provide a platform in which researchers could recreate the invasion of an antibiotic-treated human intestinal community by C. difficile.

"Using the mini-bioreactors model we showed that L. reuteri reduced the burden of C. difficile infection in a complex gut community," Britton said. "To achieve its beneficial effect, L. reuteri requires glycerol and converts it into the antimicrobial reuterin."

The literature reports reuterin as a broad-spectrum antibiotic; it affects the growth of a wide variety of bacteria when they are tested individually in the lab. What was intriguing in this study is that reuterin didn't have a broad-spectrum effect in the mini-bioreactor bacterial community setting.

"I expected reuterin to have an antibacterial effect on several different types of bacteria in the community, but it only affected C. difficile and not the good bacteria, which was exciting because it has major implications for a preventative strategy," Spinler said.

"Although these results are too preliminary to be translated directly into human therapy, they provide a foundation upon which to further develop treatments based on co-administration of L. reuteri and glycerol to prevent C. difficile infection," said co-author Dr. Jennifer Auchtung, director of the Cultivation Core at Baylor's Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research and assistant professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor.

In the future, this potential treatment could be administered prophylactically to patients before they take antibiotics known to disrupt normal gut microbes. The L. reuteri/glycerol formulation would help maintain the healthy gut microbial community and also help prevent the growth of C. difficile, which would result in decreased hospital stay and costs and reduced long-term health consequences of C. difficile recurrent infections.

More information: Jennifer K. Spinler et al. Next-generation probiotics targeting Clostridium difficile through precursor-directed antimicrobial biosynthesis, Infection and Immunity (2017). DOI: 10.1128/IAI.00303-17