Scientists find potential mechanism for deadly, sepsis-induced secondary infection

In mice, an infection-induced condition known as sepsis may increase the risk of life-threatening secondary infection by preventing recruitment of infection-fighting cells to the skin, according to new research published in PLOS Pathogens.

Infections that enter the bloodstream can trigger an immune system response known as sepsis, which leads to 5.3 million deaths each year. Most of these deaths seem to be caused not by the initial hyperactivity of the immune system, but by a subsequent phase in which the disrupted immune response opens the door for life-threatening secondary infections to set in.

Previously, Derek Danahy of the University of Iowa and colleagues showed that sepsis disrupts the immune system by reducing the amount and function of memory T cells that circulate throughout the body, recognizing and attacking specific bacteria, viruses, or cancer cells. Now, the team has examined whether sepsis has the same impact on tissue resident memory T cells (TRM), which do not circulate but stick to the skin, lungs, and gut—where infections often enter the body.

The researchers infected mice with viruses to induce production of TRM in the skin. Next, they punctured the gut to release bacteria-containing fecal material into the body, resulting in infection and sepsis. They then induced activation of the TRM and used molecular techniques to investigate the effects.

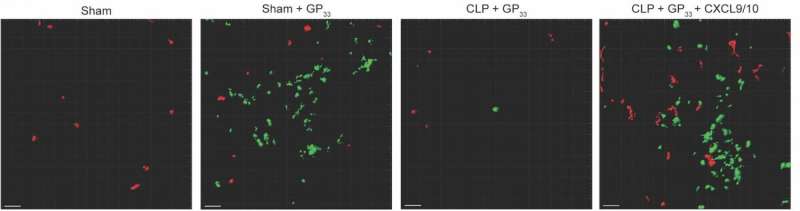

The analysis revealed that sepsis did not reduce the amount and function of TRM in the skin. However, while the function of TRM themselves was maintained, their influence was severely impaired: Normally, TRM that sense an invader can recruit other immune system cells, known as bystander T and B cells, to help fight infection, but sepsis stymied this process in the mice.

Taking a closer look, the team found that the onset of sepsis disrupts the normal activity of specific interferons, signaling proteins used for communication between immune system cells. In the mice, sepsis interrupted production of specific interferons required for TRM recruitment of bystander T and B cells, increasing the risk of secondary infection.

Further research is needed to better understand these effects, including whether they hold over the long term and for TRM in other parts of the body. Nonetheless, if the results translate from mice to humans, they could help inform strategies to prevent secondary infection in patients experiencing sepsis.

More information: Danahy DB, Anthony SM, Jensen IJ, Hartwig SM, Shan Q, Xue H-H, et al. (2017) Polymicrobial sepsis impairs bystander recruitment of effector cells to infected skin despite optimal sensing and alarming function of skin resident memory CD8 T cells. PLoS Pathog 13(9): e1006569. doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006569