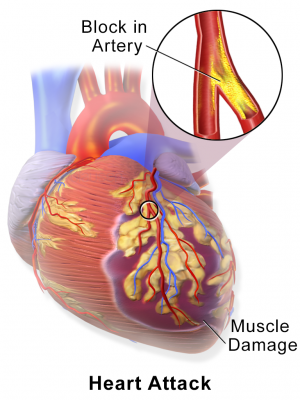

Myocardial Infarction or Heart Attack. Credit: Blausen Medical Communications/Wikipedia/CC-A 3.0

New research has identified the devastating impact of pre-existing health problems on recovery from a heart attack.

The study found that patients with chronic conditions including heart failure and high blood pressure at the time of their heart attack were more likely to die sooner.

Although there are guidelines covering how patients who have had a heart attack should be treated, they do not extend to people with multimorbidity - individuals with two or more pre-existing illnesses.

And the lack of specific guidelines may explain why some patients are dying earlier, say the scientists.

The research, conducted at the University of Leeds, revealed that certain chronic conditions cluster together, and that clustering had an association on how long a patient lived after the heart attack.

Dr Marlous Hall, from the Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine and who led the project, said: "Now we have an idea of how certain chronic conditions group together in heart attack patients, we can target research at those groups of diseases - to try and improve treatment options.

"Previous research has focused on the interplay between heart attack and single long-term conditions but as the population gets older, more and more people who experience a heart attack are already suffering from a number of other illnesses.

"Further research needs to focus on the way those other illnesses may complicate recovery from a heart attack."

The study, published in the journal PLOS Medicine, set out to examine how multimorbidity affected survival after a heart attack by analysing the records of almost 700,000 people in England and Wales in the UK who had a heart attack.

Almost 60 per cent of those patients had at least one pre-existing health condition at the time of their heart attack.

The researchers looked at the association between seven common chronic diseases and mortality rates following a heart attack. Those conditions were: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, heart failure, kidney failure, a stroke, high blood pressure and peripheral vascular disease (narrowing of the blood vessels outside of the heart and brain).

Through a statistical modelling technique called latent class analysis, the researchers were able to group the patients into three groups based not only on the number of pre-existing conditions they had but also on the way those conditions clustered with one another. The three groups were high, medium and low multimorbidity.

Patients were followed up over eight years following their heart attack.

The analysis showed that people in the high multimorbidity group were likely to have heart failure AND high blood pressure AND peripheral vascular disease prior to their heart attack.

Half of these patients had died within four and a half months, and overall they were 140% more likely to die over the study period following a heart attack compared to those with few or no multimorbidities.

People in the medium multimorbidity group were likely to have peripheral vascular disease AND high-blood pressure with a smaller proportion of patients having other conditions.

Half of these patients had died within six and a half months, and overall they were 50% more likely to die over the study period following a heart attack compared to those with few or no multimorbidities.

The researchers also looked at whether patients received the standard drug treatment following a heart attack - which includes aspirin, beta blockers and statins.

After removing those patients who were not eligible for drug therapy, due to their medical history for example - 3 per cent fewer patients in the high multimorbidity group received aspirin compared to medium and low multimorbidity groups.

In terms of beta blockers, the picture was starker, with 6 per cent fewer patients in the high multimorbidity group getting the drug compared with the medium and low groups.

With statins, 5 per cent fewer patients in the high multimorbidity group got them compared to the medium and low groups.

Dr Hall said: "Patients in the high multimorbidity group experienced a greater chance of dying sooner.

"One possible explanation for this is that some of these patients were not getting the standard drug therapy following a heart attack. But it is also likely that poorer outcomes result from the fact that there are no specific guidelines about how to treat these groups of conditions together."

More information: PLOS Medicine (2018). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002501

Journal information: PLoS Medicine

Provided by University of Leeds