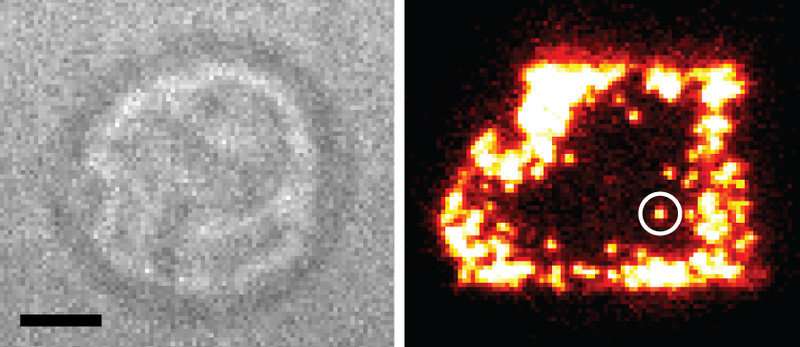

Every T cell receptor of the living T cell (left) is marked with a special marker molecule. The bottom part of the cell can be imaged with a highly sensitive microscope. Credit: Vienna University of Technology

What happens when T cells detect suspicious activity in the body? Researchers from the TU Wien and the Medical University of Vienna have revealed that immune receptors of T cells operate in unsuspected ways.

They protect us from the onslaught of bacteria and viruses and also from cancer: T cells are an indispensable part of our immune system. They constantly renew their surface with thousands of highly sensitive T cell antigen receptors, which allow them to identify atypical or foreign molecules (antigens) in our body. If such antigens are detected, for example on virally infected cells or cancer cells, T cells either directly kill these cells or alarm other immune cells to start a full-blown immune response.

Sometimes however, they also confront us with formidable challenges: they can cause rejection of transplanted organs or trigger allergies and chronic, often fatal autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Figuring out what happens on a molecular level in the course of T cell recognition is by no means a trivial task. Fundamental knowledge of all involved molecular processes, however, is critical for biomedical progress, in particular for devising effective high precision therapies against cancer and autoimmune diseases. A joint study by the TU Wien and the Vienna School of Medicine has now led to a surprising result. While most opinion leaders in the field reasoned that T cell receptors must interact with one another for effective immune-signaling, the Viennese study shows: T cell receptors act alone. The study has now been published in the journal Nature Immunology.

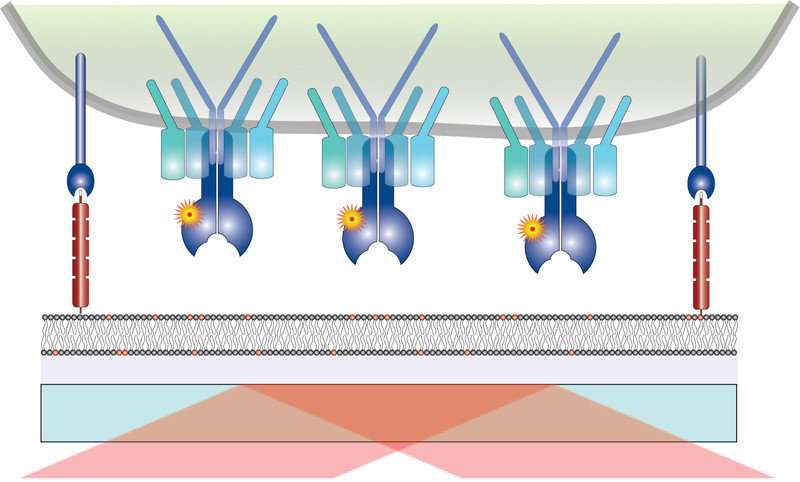

An artificial cell membrane on a glass plate binds T cells. The T cell (top, in green) has receptors (blue), which are tagged with a fluorescent molecule. Credit: Vienna University of Technology

New insights with the help of special developed research techniques

Prof. Johannes Huppa, Immunologist from the Medical University Vienna, and Mario Brameshuber, biophysicist from the TU Wien, have already joined forces several years ago. The foundation of their collaboration has been laid at Stanford University in California, where they used to work as postdocs, sharing a lab bench for one year. In Vienna they have now finally succeeded in visualizing T cell receptors on the surface of living T cells on a molecular level.

"Even though the mechanisms underlying T cell recognition are integral to the inner workings of the immune system, our understanding is still limited," Johannes Huppa says. This is because an electron microscope is necessary to see such tiny structures. With such a microscope, however, only dead cells that are specifically prepared for this kind of analysis can be studied.

"A unique aspect of our joint venture is the use of specialized microscopy approaches which allow for quasi-biochemical studies on living T cells," says Mario Brameshuber. This is possible due to a combined use of different techniques: on the one hand, specially labeled molecules are used as highly-accurate molecular probes for targeting the protein of interest, on the other hand newly developed microscopy techniques are used.

Mario Brameshuber. Credit: Vienna University of Technology

"As a biochemist, this has always been a big dream of mine, simply because this combined experimental approach allows us to study short-lived molecular processes within their native cellular context, and not in the test tube, removed from the all defining context of life," says Huppa.

No teamwork needed for T cell receptors

"The outer membrane of the T cell is not like a solid skin. Molecules embedded in the membrane are relentlessly on the move. This is also true for the receptors which bind to antigens—they constantly change their location," says Brameshuber. And so, the mechanism underlying the remarkable sensitivity of T cells towards antigens was regarded to depend on T cell receptors forming pairs or even larger groups to collectively signal once a T cell receptor binds to a single antigen.

However, as was now shown by the Viennese researchers, this assumption is just plain wrong. "Obviously the T cell receptor is a fine-tuned molecular machine, which acts as an individual entity and translates antigen-binding events into intracellular signaling with an impressive degree of processivity," says Johannes Huppa.

One can learn important lessons from how these receptors work, not only in purely academic terms but also for medical applications. Only by understanding in detail what goes wrong in T cells when they cause disease one can develop means of precise intervention. Fundamental knowledge of all involved molecular processes will allow for devising effective high precision therapies against cancer and autoimmune diseases, and also for better protecting organ transplants.

More information: Mario Brameshuber et al. Monomeric TCRs drive T cell antigen recognition, Nature Immunology (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-018-0092-4

Journal information: Nature Immunology

Provided by Vienna University of Technology