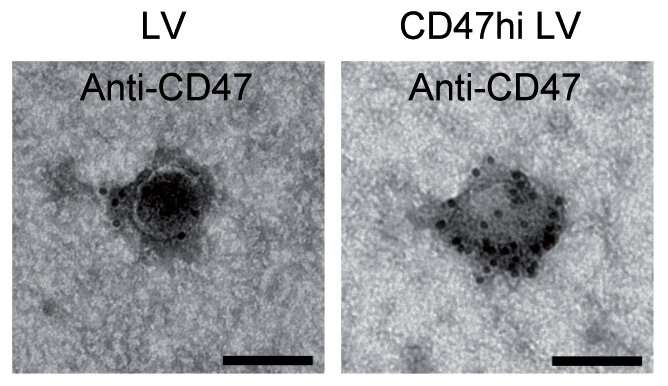

The new lentiviral vectors (LVs, black dots) harbor a protein named CD47 that protects them from the immune system Credit: M. Milani et al., Science Translational Medicine (2019)

A team of researchers from institutions in Italy and the U.S., in conjunction with several corporate entities, has found that adding a protein to lentiviral vectors can protect them from an immune system attack. In their paper published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the group describes their work in finding new ways to treat hemophilia and how well their approach worked in monkeys.

Hemophilia impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, putting people at great risk of bleeding to death from even small injuries. The heritable condition is thought to arise in people who lack a coagulation factor in their genome. Currently, scientists are trying to treat people with hemophilia using gene therapies. One such therapy involves the use of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver a gene that expresses the missing coagulation factor. Unfortunately, most people develop an immune response to AAV by the time they reach adulthood. In this new effort, the researchers have taken another approach using a different kind of vector.

The approach used lentiviral vectors (LVs) instead of an AAV; derived from HIV, the LV is less prevalent in humans, and therefore provides a better gene therapy option. But the researchers found that LVs tend to be removed from the body by phagocytes (white blood cells) before they can deliver their therapeutic payload to the target. To get around this problem, the researchers used a protein called CD47. Prior research found that CD47 is capable of avoiding detection and cleansing by phagocytes. The researchers applied it to the surface of LVs to help the LVs escape detection and subsequent cleansing.

The researchers tested their modified LVs by injecting them into six test monkeys. They report that the LVs were able to deliver their therapies to their targets (the liver and spleen) and effectively transferred genes to liver cells as planned. More testing is required, but the researchers suggest their approach could result in lower dose treatments for hemophilia, which they note would likely reduce side-effects and lower production strain on manufacturers.

Fluorescent lentiviral vectors (LV, green) were rapidly taken in by liver macrophages (KC, red) after administration to mice. Credit: M. Milani et al., Science Translational Medicine (2019)

More information: Michela Milani et al. Phagocytosis-shielded lentiviral vectors improve liver gene therapy in nonhuman primates, Science Translational Medicine (2019). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav7325

Journal information: Science Translational Medicine

© 2019 Science X Network