In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, holds a Tylox pill while sitting in a tea house in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

China has some of the strictest regulation of opioids in the world, but OxyContin and other pain pills are sold illegally online by vendors that take advantage of China's major e-commerce and social media sites, including platforms run by tech giants Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu, the Associated Press found.

These black markets supply, among others, opioid users in China who became addicted the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription, the AP found. The government admits that the scale of painkiller abuse within China remains poorly understood, making it difficult to assess abuse risks as pain care improves and China's consumption of opioids rises.

According to the latest public figures, just 11,132 cases of medical drug abuse were reported in China in 2016. But reporting is voluntary and drawn from a small sample of institutions including law enforcement agencies, drug rehabilitation centers and some hospitals. The China Food and Drug Administration said in the 2016 report that it was trying to do better but for the time being "the nature of medical drug abuse in the population cannot be confirmed."

Wu Yi, a 32-year-old singer, survived cancer only to find he couldn't stop taking OxyContin. He said his doctor told him OxyContin is not addictive and that he could take as much as he needed. Because Wu was never identified as having a substance abuse problem, he is unlikely to have appeared in the government's tally.

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Tylox user Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, pauses while walking along a street near the old city walls in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

As his habit worsened, Wu started chewing OxyContin to intensify its effect and downed vast quantities of Chinese liquor and sleeping pills.

"I feel I am kind of like a drug addict, but I cannot do anything about it," he told AP earlier this year.

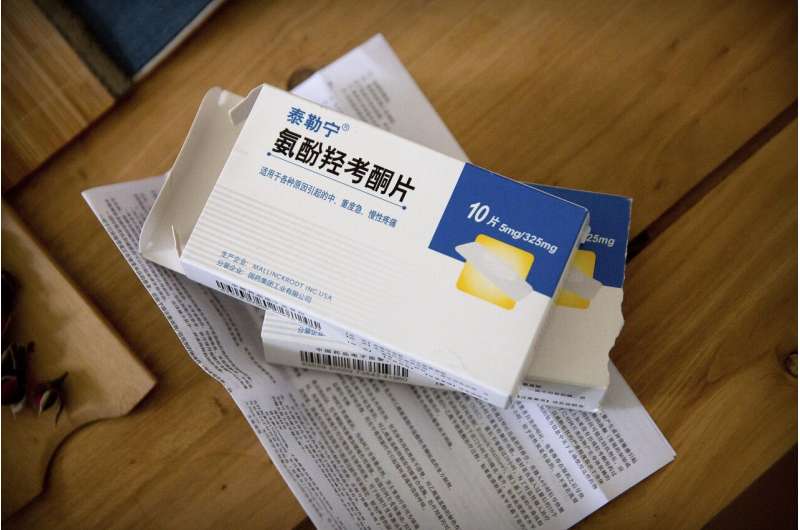

Despite the officially low numbers, the Chinese government was worried enough about pain pill abuse that it pulled combination opioids from most pharmacies in September. Among the pills targeted was Tylox, made by the drug company Mallinckrodt's subsidiary SpecGx.

The risks of opioid abuse in China may be growing as pharmaceutical companies look abroad to make up for falling opioid prescriptions in the U.S. OxyContin has been marketed in China with the same tactics that drove Purdue Pharma into bankruptcy in the U.S. and allegedly helped spark the deadliest drug abuse epidemic in U.S. history, according to interviews with current and former employees and documents published by the Associated Press last month.

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, talks about his addiction while sitting near boxes of Tylox pills he earlier purchased illicitly in a tea house in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill addiction is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid addiction the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Purdue Pharma's China affiliate, Mundipharma, has denied allegations of wrongdoing and says it has "checks and balances in place including internal audits and reviews to ensure strict compliance with medical protocols, laws and regulations."

U.S. social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, have also struggled to stop illicit listings for opioids. As opioid overdose deaths surged past 400,000 in the United States, online trafficking networks, many of which sourced chemicals in China, made it easier to buy black market drugs.

But despite China's scrupulous monitoring of online activity, the AP found black markets for OxyContin and other pain pills on the open internet.

An AP survey of China's major e-commerce and social media platforms identified thirteen vendors selling opioid painkillers. They often used one platform to draw in customers and another for sales.

In this March 28, 2019, photo, boxes of Tylox pills Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, earlier purchased illicitly sit on a table at a tea house in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Eight of them used Tencent's popular WeChat app. Last week, in a closed group for cancer patients on Tencent's QQ app, one person tried to buy OxyContin and another offered to sell Tylox. Two vendors on Zhuan Zhuan, a second-hand marketplace backed by Tencent, offered to sell OxyContin, Tylox, and/or MSContin.

"We are vigilant against unscrupulous parties making unauthorized use of our platforms and services that include QQ and WeChat to pursue illegal activities," Tencent said in a statement, adding that it encourages users to report illegal activities.

58.com, which runs Zhuan Zhuan, didn't respond to requests for comment.

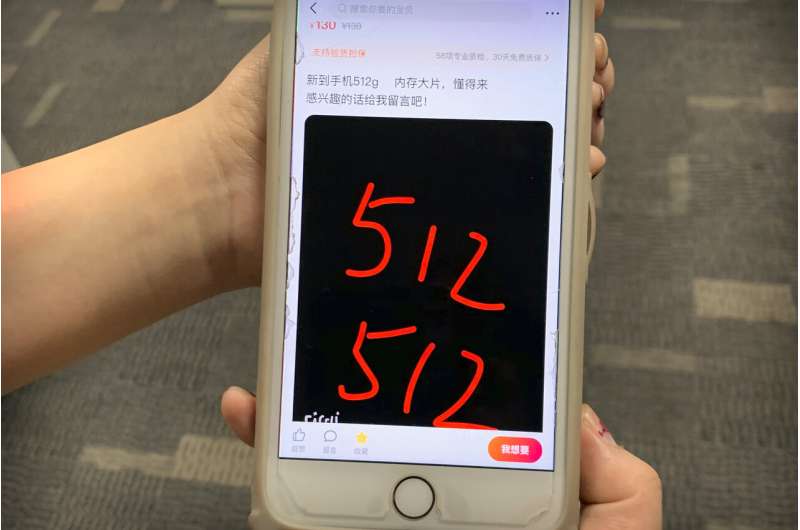

On Alibaba's second-hand marketplace, Xianyu, known as Idle Fish in English, AP found seven accounts, which appeared to be run by six different people, offering OxyContin or Tylox.

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, shows a smartphone photo of an earlier purchase he made of Tylox pills while sitting in a tea house in Xi'an in northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

One vendor created a fake storefront on Xianyu to execute transactions. After arranging an OxyContin sale on WeChat, the vendor sent a special link for a product listing on Xianyu for "flowers" that cost the agreed price: 1,200 yuan for 10 boxes of 10mg OxyContin pills. "Tell me when you've paid," the vendor wrote. "Pay before six and ships today."

Idle Fish said it removed listings that violated marketplace policies after AP pointed out illicit opioid sales. The company said it prohibits "illegal behavior by third-party sellers on the platform," proactively monitors listings and welcomes user reports to facilitate takedowns.

A thread about quitting drugs on Tieba, a forum run by tech giant Baidu, also led to opioid dealers. AP identified one person on Tieba selling OxyContin in December and earlier this year made contact with two other people selling painkillers and sleeping pills. One swore that OxyContin is not addictive and said it makes sex better and gives you an unparalleled "feeling of floating."

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, checks his phone while standing in an elevator lobby in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Baidu said it constantly monitors its platforms keep them free of illegal activity, facilitates user reports of bad behavior and reports infractions to the police.

In addition to the active vendors AP identified, Tianya, an internet forum, had dozens of postings by people selling or seeking OxyContin stretching back over several years. Wu, the cancer survivor, said he was offered pills after posting his contact information in a thread about OxyContin on Tianya in April. Tianya didn't respond to requests for comment.

To evade detection, sellers used partial names or slang and posted stock photos of things like socks, a cactus or elaborate pink ceiling lamps. Postings often disappeared.

The AP did not make any purchases and could not confirm the authenticity of the pills.

One significant regulatory loophole in China is that family members try to resell OxyContin left over after a loved one dies.

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, opens a package of Tylox pills he earlier purchased illicitly in a tea house in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

That's what Zhou Shalu did after her mother died of lung cancer and left her with hundreds of 40mg OxyContin pills, worth more than $1,000, sitting on a faux-marble coffee in her living room.

The pills had been a lifeline for her mother in her last months, easing a pain so fierce it stopped her from eating, speaking and even opening her eyes. But now Zhou didn't know what to do with them.

She was afraid to just throw them in the trash. So she offered the pills at a 35 percent discount in cancer support chat groups and internet forums. A pharmacist, Zhou knew OxyContin could be abused and asked all interested buyers to send her copies of their medical records.

"No sales to drug dealers," she wrote in an Aug. 29 post offering 20 boxes of 40mg OxyContin on the popular microblogging site Weibo, which has since been deleted.

In this March 27, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, smokes a cigarette while talking about his Tylox addiction in a restaurant in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

A month after her mother's death, she said she still hadn't found any buyers she considered legitimate.

Sina Corp., which runs Weibo, said that after finding violations, it ran a campaign in March to clean-up illicit content about medicines and medical equipment and would continue to improve key word screening and image recognition.

In August, the Ningjiang District People's Court in northeastern Jilin province convicted three people of trafficking thousands of pills of OxyContin and MSContin—both slow-release opioids sold by Purdue Pharma's China affiliate, Mundipharma.

According to a copy of the judgment, they acquired pills from families who, like Zhou, had extra pain medicine. With online names like "Invincible Benevolent," "Soul Ferryman," and "Little Treasure," the network used WeChat, Xianyu and Zhuan Zhuan to find customers and execute sales, and delivered pills using a major courier service, SF Express. Among the witnesses was a customer who became addicted to opioids after taking them for a toothache and leg pain.

-

In this March 27, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, holds a container of Tylox pills while sitting in a restaurant in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this March 27, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, holds a Tylox pill while sitting in a restaurant in Xi'an, in northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill addiction is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this March 28, 2019, photo, Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, rolls up his sleeve while walking along a street in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this March 27, 2019, photo, people eat at an outdoor night market in Xi'an, northwestern China's Shaanxi Province, similar to one at which Yin Hao, who also goes by Yin Qiang, was injured during a fight that led to his initial prescription for Tylox. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this March 28, 2019, photo, people shop at a pharmacy that sold Tylox without a prescription in Xi'an in northwestern China's Shaanxi Province. Despite officially low numbers of prescription drug abuse, the Chinese government was worried enough about pain pill abuse that it pulled Tylox from most pharmacies in September. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid addiction the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 24, 2019 photo, a post from a vendor offering Tylox for sale on Xianyu, Alibaba's online second-hand marketplace, is seen on a smartphone in Shanghai, China. Officially, pain pill addiction is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. Tylox pills are known on the black market as 512s, after the number marked on their side. The text of the ad reads "Newly arrived 512g cell phones, loaded with blockbuster movies, who understands come. If interested, leave me a message!". (AP Photo/Erika Kinetz)

-

In this Dec. 24, 2019 photo, a listing using bogus product photos from a vendor offering OxyContin pills for sale on Xianyu, Alibaba's online second-hand marketplace, is seen on a smartphone in Shanghai, China. Officially, pain pill addiction is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. The text of the ad reads "Home-use OxyContin brand white color yellow color 10-40 with box, if interested leave me a message!". (AP Photo/Erika Kinetz)

-

In this Dec. 27, 2019, photo, screenshots of postings from sellers offering Tylox, left and right, and OxyContin, center, pills for sale on major Chinese e-commerce and social media platforms are seen on a display in Beijing. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019, photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, smokes a cigarette while looking out the window of his rented room in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 5, 2019 photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, sings a song he composed while sitting in his rented room in Shenzhen, southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 5, 2019 photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, sits in his rented room near his crutch and the portable amplifier he uses to sing songs for money in Shenzhen, southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this December 6, 2019, photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin addiction, leaves his rented room to go sing songs for money at all night-restaurants and clubs in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019, photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, crosses a street while on his way to sing songs for money at all night-restaurants and clubs in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 5, 2019 photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, holds a playlist of songs he sings for money while sitting in his rented room in Shenzhen, southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019, photo, passers-by talk to Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, as he waits for a break in the rain while making his rounds to sing songs for money at all night-restaurants and clubs in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019 photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, sings a song for customers at an all-night restaurant in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019 photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, sings a song for customers at an all-night restaurant in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

-

In this Dec. 6, 2019, photo, Wu Yi, who has struggled with Oxycontin abuse, wheels his portable amplifier past customers at an all-night restaurant in Shenzhen in southern China's Guangdong Province. Officially, pain pill abuse is an American problem, not a Chinese one. But people in China have fallen into opioid abuse the same way many Americans did, through a doctor's prescription. And despite China's strict regulations, online trafficking networks, which facilitated the spread of opioids in the U.S., also exist in China. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

"Mundipharma China has no knowledge of the diversion of its products on e-commerce and social media platforms," the company said in a statement to AP.

Mallinckrodt's specialty generics subsidiary SpecGx sells its pain pills to a Chinese importer. In a statement, the company said it "has no manufacturing, distribution, sales force or in-country presence in China."

China's National Narcotics Control Commission and China's National Medical Products Administration did not respond to requests for comment.

© 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.