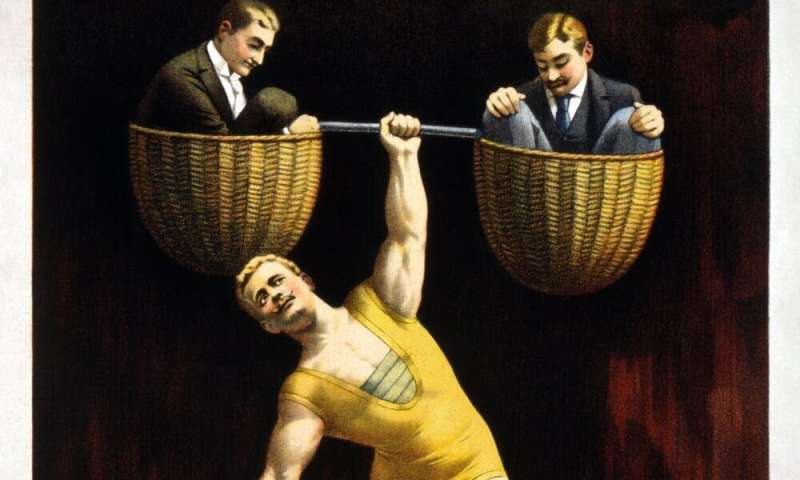

A poster of Eugen Sandow lifting the human dumbell. Credit: US Library of Congress Prints

The Victorian era is often remembered as an age of industrial innovation, staunch morals and hard work. When we imagine the stereotypical Victorian, we often picture stiff collars and heavy, head-to-toe dresses—not celebrity weightlifters or homemakers practicing calisthenics. But it turns out our obsession with physical fitness isn't just because of 20th century stars like Jane Fonda, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson. In fact, the Victorian age saw the beginnings of modern celebrity fitness culture and new forms of exercise—which we might credit for our current obsession today.

The Victorian fitness craze might first be traced back to the publication of Donald Walker's book "British Manly Exercises" in 1837. The book included diagrams showing proper rowing technique, horse-riding instructions and detailed guidance on how to lunge, vault and wrestle. Walker also included exercises borrowed from different cultures, such as strength-training using clubs from India which offered "the most effectual kinds of athletic training known anywhere," according to a British officer stationed in the country. These forms of exercise quickly became popular, often because they were adopted by the British military.

Achieving physical fitness gradually became a cornerstone of Victorian values. This was largely inspired by cultural trends such as "Muscular Christianity", which originated in England in the mid-19th century. Muscular Christianity emphasized the importance of training the body to reflect devotion to both God and society.

One author claimed that strong Christian bodies could be used to protect the weak, advance all "righteous causes," and promote the "subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men".

Home exercise

Although hobbies like riding horses and playing golf remained popular with the upper-classes, exercise done at home became increasingly favored by the emerging Victorian middle class. "The Portable Gymnasium" became a best-seller after it was published in 1861. It claimed there were numerous benefits to undertaking what the author called "gymnastic exercises," which were said to develop and restore the human form. Some of these exercises look similar to what we'd do today. Readers were instructed to use the portable gymnasium to perform body-toning exercises such as lateral extensions and head rotations.

Exercise had grown so popular that by 1865, the Royal Patent Gymnasium – a huge outdoor gym—was opened in Edinburgh. It regularly attracted thousands of fitness fanatics each day. It featured The Giant Sea Serpent, an enormous circular rowing machine which could reportedly seat 600 people at a time.

By the late 19th century, James Cantlie, a Scottish medical practitioner, had developed "new" exercise regimes that could be done at home. These included an elaborate routine of stretches to be performed morning and evening—accompanied by bathing and muscle massage.

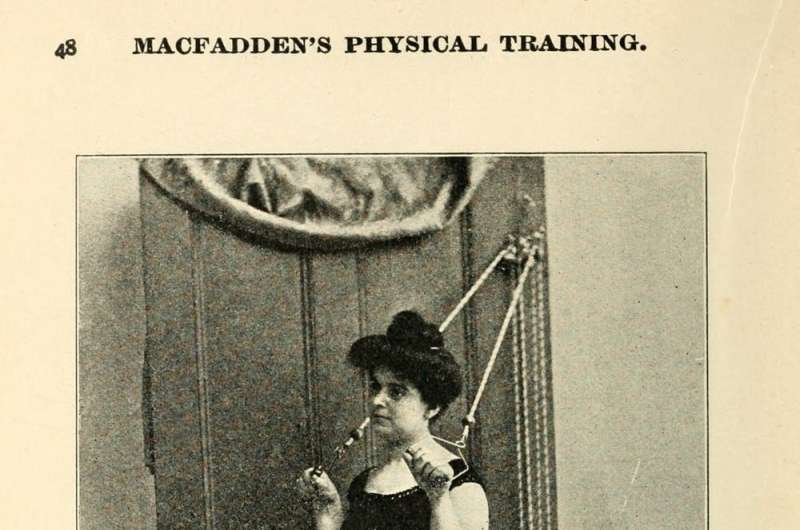

A woman uses Bernarr Macfadden’s exercise apparatus. Credit: Bernarr A. Macfadden, Macfadden's Physical Training, 1900

Cantlie argued that they were especially suitable for the over-50s as they did not cause too much exertion. He also founded the British Institute of Physical Training in 1889, where men and women, young and old, could attend exercise classes where they would practice Cantlie's so-called "physical jerks"—rhythmic movements to strengthen and tone the body.

People who came to the classes were encouraged to practice the exercises at home on a daily basis—but were simultaneously warned they needed to return regularly to learn new exercises and ensure they were using the correct techniques. Cantlie also made other lifestyle recommendations, such as insisting that wearing kilts promoted "the health and strength of lads" as they didn't restrict the body's natural movements.

Cantlie's system was just one among many other competing exercise regimes. However, his system served as inspiration for the daily exercise regime members of the Outer Party were required to do in George Orwell's "1984" more than half a century later.

Other popular approaches to fitness and health included a regime developed by one Dr. E H Ruddock, whose book Vitalogy (1899), promoted good posture, "vitativeness" (love for life), and only moderate exercise to avoid overtiring the body.

Fitness "influencers"

The Victorian age also saw the rise of the celebrity fitness guru. At the end of the 19th century, one of the most famous was German-born Eugen Sandow. Sandow staged elaborate strongman shows throughout Europe and America and built up a global publishing empire through his magazine Physical Culture, which included profiles and images of bodybuilders and articles on the merits of different exercises. He credited his approach to exercise, built around dumbbell training, with transforming his physique—and recreated poses from classical Roman and Greek sculpture in order to showcase his body.

Sandow was a trailblazer who inspired others, including the American bodybuilder Bernarr Macfadden. Just a year younger than Sandow, Macfadden claimed that he was weak and sickly as a child. He argued in his first book, Macfadden's Physical Training, which was published in 1900, that through a carefully managed vegetarian diet and regular weightlifting, anyone could overcome ill-health, just as he had done. His system had specific guidance for young men, young women, middle-aged men and middle-aged women, and appropriate exercises "as the years wane," all to be performed at home using his simple stretching device.

After a series of military setbacks, Britain was gripped by a sense of anxiety by the end of the Victorian era about its place in the world. Many worried that industrialization—which had driven the expansion of the British Empire – had made bodies weak. British people feared that they had become trapped indoors in factories and offices, made slovenly by technological change. Worry about national fitness persisted into the early 20th century, and the exercise craze showed no signs of stopping.

For many middle and upper-class Victorians, having a healthy body was an expression of religious and national devotion. Being able to achieve it in the comfort of the home was an added bonus. The Victorian obsession with celebrating athletic prowess and striving to better their bodies physically is not unlike society's obsession with fitness today.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()