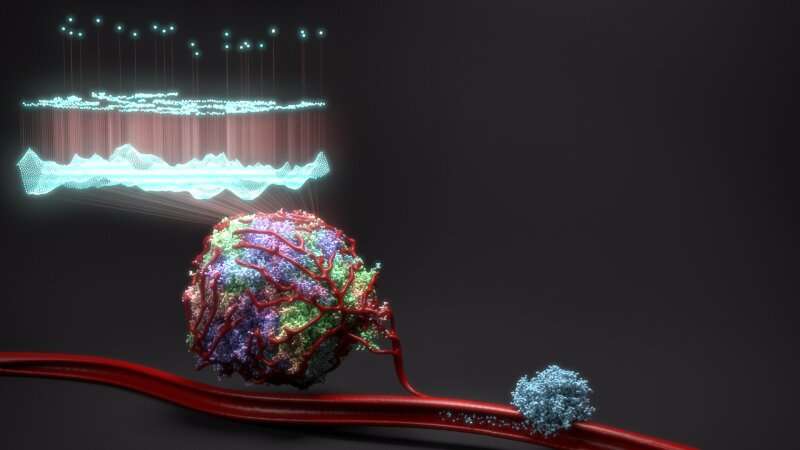

Illustration of a diverse primary tumour whose genome has been sequenced to identify 23 key genes that can predict survival chance. The mass on the right represents a secondary metastatic tumour seeded by cancer cells in the bloodstream. Credit: Jeroen Claus, Phospho Biomedical Animation

A collection of papers published in Nature journals have transformed our understanding of how lung cancer evolves over time, in particular how the surrounding environment and immune system drives changes.

The collective findings from the pioneering TRACERx study have already changed the way researchers and clinicians view lung cancer, leading to new clinical trials and research projects aimed at tackling these hard-to-treat tumours.

The process of cancer evolution closely mirrors the way that species evolve through natural selection. As lung cancer cells multiply, mutations take place in their DNA which can help, harm, or have no effect. A helpful mutation may make the cell resistant to certain treatments or able to more quickly digest the nutrients it needs to divide.

But observing the product of this evolution only provides part of the picture. For example, in order to understand the variety of different finches on the Galapagos Islands, Charles Darwin needed to consider the different environments in which each of the finches lived.

The same is true for studying cancer evolution. You need to understand the surrounding environment, that is the body, to understand why and how a tumour is going to evolve.

This complex challenge is being tackled by the TRACERx consortium, led by researchers at the Crick and UCL and, funded by Cancer Research UK.

Findings from the first 100 patients studied have now been brought together in this special Nature collection. This set of papers has found one key to understanding tumour evolution: the immune system.

"It is only by investigating the complex ecosystem within and around a tumour, as the cancer develops, that we can see not just the evolutionary changes themselves but what's driving them," says Charles Swanton, lead researcher for the TRACERx project.

Amongst the most significant findings from the study so far are:

- that unstable chromosomes are the driving force behind genetic diversity within tumours;

- the ability to detect whether a patient's cancer will come back up to year before it becomes visible on a scan;

- the discovery of different mechanisms by which tumours can evolve to evade the immune system;

- why some cancer cells exhibit an unusual phenomenon called whole genome doubling, where every chromosome is duplicated;

- how to accurately identify high-risk tumours after surgery;

- how to track the spread of disease in the blood with minimally invasive approaches using circulating tumour DNA;

- the immune cell responses key to developing future personalised immunotherapies against truncal mutations present in every tumour cell.

Two new papers are also being published as the collection launches. The first led by researchers at the Institute of Cancer Research, London, used AI to analyse the patterns and prevalence of immune cells within different areas of lung tumours. They found that patients with more 'immune cold' regions within their tumour were more likely to relapse. This work could help doctors predict how well a patient will respond to certain treatments, and even help personalise care.

The second, led by researchers at UCL, found that if a type of immune cell, T cells, are exposed to a tumour for prolonged periods they can stop working effectively. This is important as T cells are on the front-line of the body's defences, destroying cancerous cells and signalling to other immune cells to active them to the threat.

"Thanks to the tremendous scientists at the Francis Crick Institute, UCL and Manchester Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre and the Institute of Cancer Research involved in TRACERx in the UK, this first set of papers has unlocked a great deal of knowledge regarding the relationship between non-small cell lung cancer and the immune system, showing how much we can learn from tracking cancer's evolutionary trajectory, from diagnosis through to relapse," adds Charlie.

"As the project continues, I hope it will help to improve diagnosis and treatment, ultimately taking a practical step towards further improving clinical outcomes through precision medicine."

Journal information: Nature

Provided by The Francis Crick Institute