Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Materials scientists at the University of Jena have developed a bone replacement based on calcium phosphate cement and reinforced with carbon fibers. The fibers increase damage tolerance and ensure that cracks in the material repair themselves.

The body is able to treat many injuries and wounds all by itself. Self-healing powers repair skin abrasions and enable bones to knit back together. However, doctors often have to lend a helping hand to repair bones after a fracture or due to a defect. Increasingly, bone replacement materials are being used, which partially or completely restore the form and function of the bone at the site of the damage. To ensure that such implants do not have to be replaced or repaired through extensive surgery in the event of damage, they should themselves possess self-healing capabilities. Materials scientists at Friedrich Schiller University Jena have now developed a bone replacement material that minimizes the extent of damage to it and at the same time repairs itself. They report on their research in the prominent research magazine Scientific Reports.

Minimally invasive use of calcium phosphate cement

The experts from Jena, who collaborated with colleagues from the University of Würzburg, concentrated on what is called calcium phosphate cement—a bone substitute that is already widely used in medicine. On the one hand, the material stimulates bone formation and increases the ingrowth of blood vessels. On the other hand, it can be introduced into the body as a paste in a minimally invasive procedure. There, its malleability allows it to bind closely to the bone structure.

"Due to its high degree of brittleness, however, cracks form in the material when it is subjected to excessive load. These cracks can quickly widen, destabilize the implant and ultimately destroy it—similar to concrete on buildings," explains Prof. Frank A. Müller from the University of Jena. "For this reason, calcium phosphate cement has so far mainly been used on bones that do not play a load-bearing role in the skeleton, for example in the mouth and jaw area."

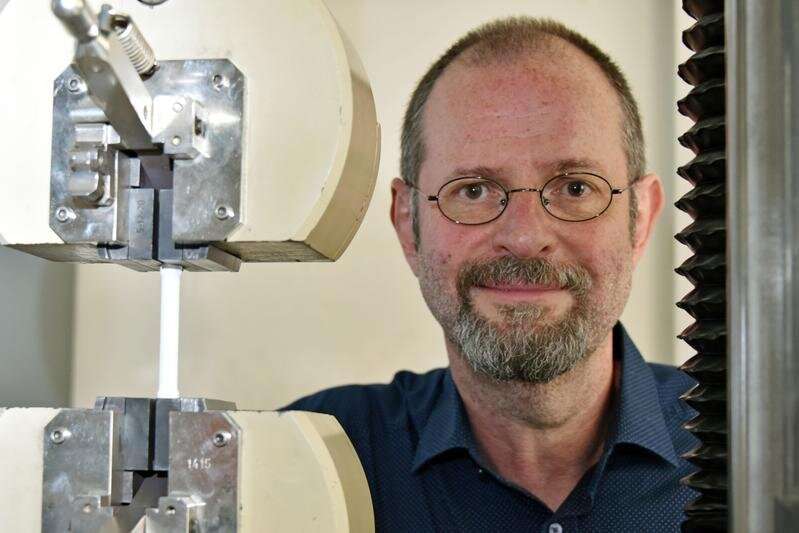

Prof. Dr Frank A. Müller, Chair of Colloids, Surfaces and Interfaces at Otto-Schott-Institut of Materials Research (OSIM) at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena. Credit: Anne Günther/FSU

Bridging and refilling cracks

The materials scientists in Jena have now developed a calcium phosphate cement in which cracks do not develop into catastrophic damage. Instead, the material itself seals them. This is achieved by adding carbon fibers to the material.

"Firstly, these fibers significantly increase the damage tolerance of the cement, because they bridge cracks as they form, and thus prevent them from opening further," Müller explains. "Secondly, we have chemically activated the surface of the fibers. This means that as soon as the exposed fibers encounter body fluid, which collects in the openings created by the cracks, a mineralisation process is initiated. The resulting apatite—a fundamental building block of bone tissue—then closes the crack again."

The Jena scientists have simulated this process in their experiments by deliberately damaging the calcium phosphate cement and healing it in simulated body fluid. This intrinsic self-healing ability—and the greater load-bearing capacity associated with fiber reinforcement—could considerably expand the areas in which bone implants made of calcium phosphate cement can be used, which could possibly also include load-bearing areas of the skeleton in the future.

More information: Anne V. Boehm et al. Self-healing capacity of fiber-reinforced calcium phosphate cements, Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-66207-2

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by Friedrich Schiller University of Jena