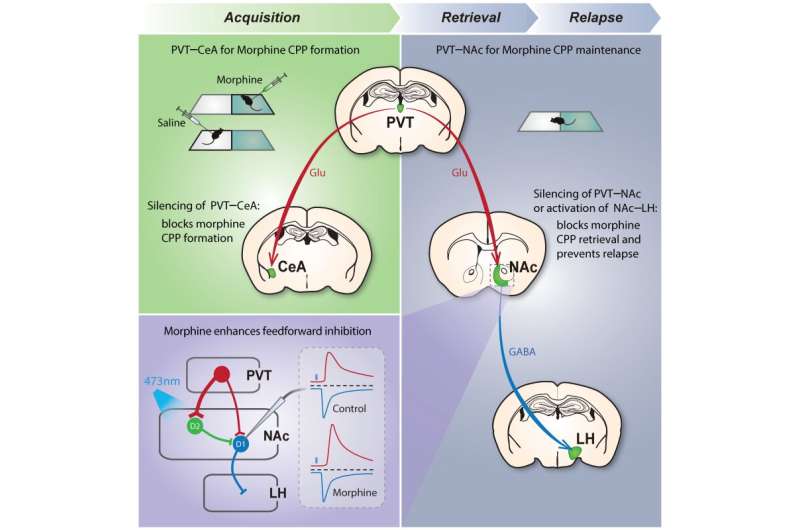

The PVT/CeA pathway associates opiate reward to the environment, whereas transient manipulation of the PVT/NAc pathway or its downstream NAc/LH pathway during retrieval erases opiate-associated memory and causes enduring protection against relapse to opioid use. Credit: SIAT

Research surrounding addiction often points to the reward of a "high" as the primary motivation for drug use and relapse. However, it's often the acute symptoms of withdrawal, including nausea, vomiting, pain and cramping, that drives a return to drugs for relief.

The most difficult part of treating addiction is to prevent relapse, especially for opioids. Opioid withdrawal symptoms are severe and relapse among users is common.

Both the reward of the "high" and the alleviation of painful withdrawal symptoms can serve as powerful memory cues that trigger a relapse.

Researchers from the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology (SIAT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Stanford University interrupted the brain pathway responsible for morphine-associated memories in mice, that is, "erasing" the drug-associated memory from the brain.

The study was published in Neuron on July 16.

The researchers put the mice in a two-sided chamber for training. They were given saline on the one side, and a small dose of morphine on the other side. After five days, the mice unsurprisingly developed a compulsive preference for the chamber with morphine and were considered addicted.

Then, by using light from an optical fiber, the scientists could turn the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) pathway off to alleviate opiate withdrawal symptoms.

When the withdrawal pathway from the PVT was turned off or silenced, the mice's preference for the drug-associated chamber went away. If tested a day later, when the withdrawal pathway could theoretically function again and environmental cues could reactivate the memory, the scientists were surprised to find that the mice still showed no preference for the drug-associated chamber.

"Our data suggest that after silencing this PVT pathway, environmental cues will not work to reactivate this memory," said Chen Xiaoke, an associate professor of biology at Stanford University.

Even when morphine was reintroduced to the chamber, the mice still did not preferentially go there, and this held true even two weeks later. It was as if the animals had completely forgotten the effects—both good and bad—of the drug.

"Our success in preventing relapse in rodents may one day translate to an enduring treatment of opioid addiction in people," said Zhu Yingjie from SIAT, the co-corresponding author of this study.

More information: Piper C. Keyes et al. Orchestrating Opiate-Associated Memories in Thalamic Circuits, Neuron (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.028

Journal information: Neuron

Provided by Chinese Academy of Sciences