Why naming neurons can help cure brain disease

The human brain has about 100 billion neurons, linked in intricate ways, that the Spanish neuroanatomist Ramón y Cajal compared to "the impenetrable jungles where many investigators have lost themselves."

But to decipher how the brain works and understand how it can go awry in many diseases, it is essential to figure out how many classes of neurons it actually has and how they are connected with each other.

Now, in a paper published recently in Nature Neuroscience, a Columbia-led international group has proposed a unified nomenclature of the neurons of the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the brain that plays a key role in attention, perception, awareness, memory, language, and consciousness.

"A broadly agreed-upon classification is essential to archiving the hundreds of neuron types and their properties," said Rafael Yuste, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University. "If we could decipher how the cortex is built and what it does, one could scientifically understand our minds."

How to classify neurons has been much debated since the inception of modern neuroscience. Many efforts to describe their anatomical, physiological, and molecular features have been unsuccessful due to their cellular diversity, Yuste said.

During the last two decades, however, the Human Genome Project has produced a host of molecular methods that enable identifying and phenotyping cells in great numbers.

"This molecular revolution is generating databases that are complete, accurate, and permanent—a triumvirate considered the golden standard of biology," Yuste said.

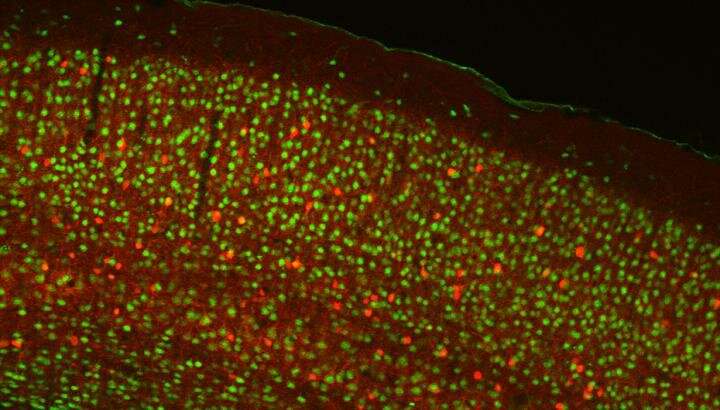

In particular, using highly automated techniques that sequence the RNA of individual cells rapidly and cost-effectively, several groups have started to assemble datasets to classify cell types in the cortex. "The approach enables sampling tens of thousands of cells, generating what could be an essentially complete coverage of all the existing cell types in the cortex," Yuste said.

Two years ago, during discussions at an international meeting on cortical neurons in Copenhagen, participants agreed that the time was right to finally tackle the creation of a unified classification.

A group of 74 scientists proposed the use of single-cell RNA sequencing as the skeleton for a unified classification of cortical neurons. Known as the "Copenhagen Classification," the proposal is described in the Nature Neuroscience article.

"This could be a historic event, as it tackles one of the core problems in neuroscience," Yuste said. "A unified framework is important not only for researchers and clinicians interested in understanding how the cortex works but also could inspire similar community classifications of cells."

In fact, he added, "there are major consortia worldwide charted with classifying all the cells in the body something that could be a breakthrough for biology and medicine."

With neuroscience rapidly transitioning to digital data, the researchers propose the classification be updated regularly using a type of algorithm often employed by the software industry for automatic data aggregation.

"It's exciting to think that neuroscientists in the not-too-distant future could finally, through technology, break the impasse that has plagued us for centuries," Yuste said.

More information: Rafael Yuste et al, A community-based transcriptomics classification and nomenclature of neocortical cell types, Nature Neuroscience (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-020-0685-8