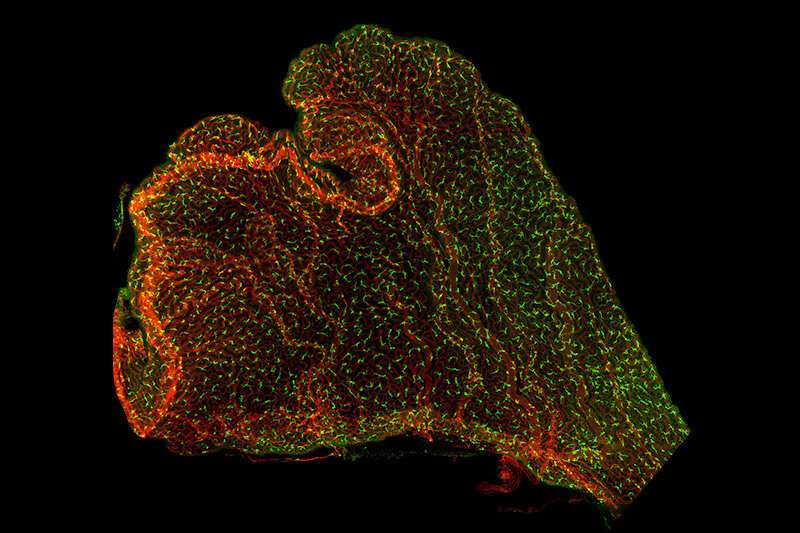

Immune cells (in green) on the mouse choroid plexus, with blood vessels in red. Credit: Shipley et al., Neuron 2020, 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.024

Floating in fluid deep in the brain are small, little understood fronds of tissue. Two new studies reveal that these miniature organs are a hotbed of immune system activity. This activity may protect the developing brain from infections and other insults—but may also contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders like autism.

"There is a correlation between maternal illness during pregnancy and autism, and we wanted to investigate how this is happening," says Maria Lehtinen, Ph.D., a neurobiologist at Boston Children's Hospital who led both studies. "It's a very challenging process to study in the lab."

The Lehtinen laboratory, part of Boston Children's Department of Pathology, is one of the few in the world to study the choroid plexus. Anchored in each of four channels in the brain called ventricles, the choroid plexus produces the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that bathes the brain and spinal cord. Lehtinen has shown that the choroid plexus regulates brain development, by secreting instructive cues into the CSF, and provides a protective brain barrier in early life, preventing unwanted cells or molecules in the blood circulation from freely entering the brain.

But what happens when that barrier is challenged? The lab's new work offers an unprecedented real-time view of the choroid plexus in a mouse model, providing a glimpse of how disturbances of the mother's immune system during pregnancy disrupt the developing brain. It shows that the choroid plexus can act as a conduit for inflammation, which can result from maternal infection, stress from the environment, and other factors.

A window on the choroid plexus

Because it is so deep in the brain, the choroid plexus is normally very difficult to view. The first study, published in Neuron, built special imaging tools to capture the action of cells in and around the choroid plexus in adult mice.

Led by Frederick Shipley, Ph.D., Neil Dani, Ph.D., Lehtinen, and Mark Andermann, Ph.D., at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center, the researchers carefully removed part of the skull bone and inserted a piece of clear plexiglass, creating a "skylight" into the brain. Using live two-photon imaging, which provides three-dimensional views of deep tissues, they were able to observe the choroid plexus in real time. They tracked the movements of immune cells, monitored changes in calcium (a proxy for cellular activity), and measured the secretions of cells in the choroid plexus.

The choroid plexus, inflammation, and the developing brain

The second study, published today in Developmental Cell and led by Jin Cui, Ph.D., applied similar techniques to observe the effects of maternal inflammation on the brains of embryonic mice. To mimic maternal inflammation, the team introduced a molecular messenger known as a cytokine to artificially trigger an inflammatory immune response into the embryos' brains, then carefully placed the embryos in an imaging chamber and conducted two-photon imaging of their brains through a tiny "skylight."

"We wanted to see how the maternal immune response is propagated into the brain, and how the choroid plexus responds to external insults during early development," says Cui.

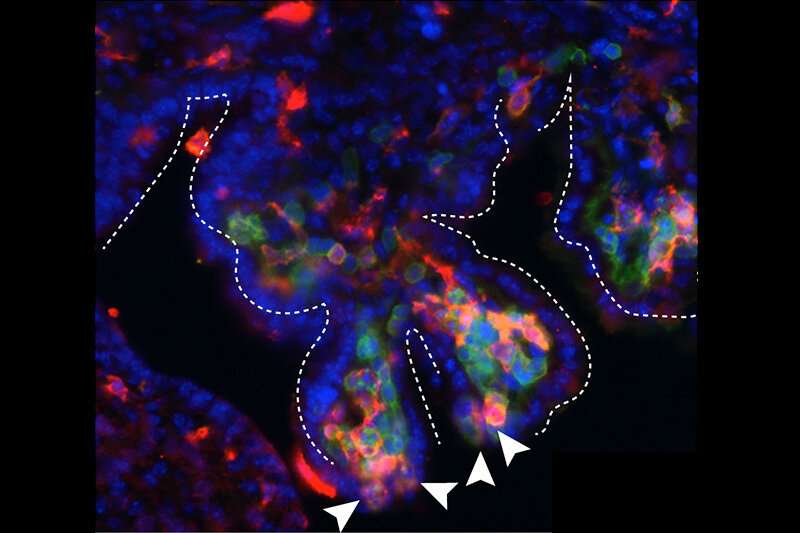

The arrowheads show immune cells (red, macrophages; green, leukocytes) gathered at "hotspots" in the choroid plexus, from which they appear to enter the cerebrospinal fluid. Credit: Jin Cui, PhD, Boston Children's Hospital

The mock maternal inflammation was enough to draw immune cells known as macrophages to the embryo's choroid plexus. Imaging showed the cells conducting active "surveillance" in the choroid plexus even in this early embryonic stage.

"The embryonic brain is very small, so it's hard to get good resolution, but we could see macrophages moving and extending little arms as if sampling their environment," says Lehtinen. "This has never been captured before."

Markers of future autism?

The team also found an increase in inflammatory signals, particularly CCL2, in the embryonic CSF, and saw evidence that those signals were produced by immune cells at the choroid plexus.

"Many of these markers, including CCL2, are also upregulated in autism patients," notes Cui.

Further experiments showed that CCL2, on its own, was sufficient to recruit and activate immune cells at the choroid plexus. Looking at tissue specimens, the team saw evidence that macrophages had breached the choroid plexus barrier, crossing into the CSF from specific "hotspots" at the tips of the choroid plexus.

"We have added evidence that the inflammatory response perturbs the development of the brain," says Cui. "Previous studies from others have shown that maternal inflammation causes brain malformations in mouse models very early in life, and similar malformations can be seen in some autism patients."

A treatment to protect the brain?

In some of their experiments, the researchers observed patches of brain disorganization after the mice were born. But of course, much more work is needed to connect the dots from maternal inflammation to the choroid plexus to disorders like autism. Even more work would be needed to translate that knowledge into treatment.

"The goal would be to see if preventing the breaching of the choroid plexus barrier could slow or prevent the progression of disease in the brain," says Lehtinen. "That will involve collaborating with many different groups in multiple fields, as well as further advances in imaging technology that are currently underway."

More information: Developmental Cell (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.09.020

Neuron (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.024

Journal information: Developmental Cell , Neuron

Provided by Children's Hospital Boston