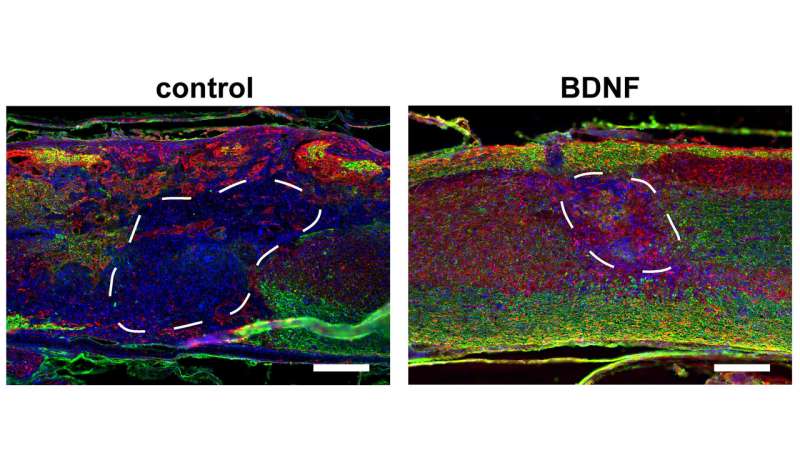

Images show myelinated axons in biomaterial scaffolds eight weeks after injection into the injured cord of a mouse. Scaffolds were fabricated from hyaluronic acid (HA) with a regular network of cell-scale macropores and loaded with gene therapy vectors encoding for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), to promote axonal survival and regeneration. These were compared to control scaffolds, which were lacking the BDNF vector. Images show dense infiltration of cells (shown in blue, cell nuclei), axons (shown in red in A, NF200 protein) and myelinating glial cells (shown in green, myelin basic protein) in the BDNF-laden scaffolds. Scale bars = 200 μm. Credit: Seidlits et al.

Spinal cord injuries can be life-changing and alter many important neurological functions. Unfortunately, clinicians have relatively few tools to help patients regain lost functions.

In APL Bioengineering, researchers from UCLA have developed materials that can interface with an injured spinal cord and provide a scaffolding to facilitate healing. To do this, scaffolding materials need to mimic the natural spinal cord tissue, so they can be readily populated by native cells in the spinal cord, essentially filling in gaps left by injury.

"In this study, we demonstrate that incorporating a regular network of pores throughout these materials, where pores are sized similarly to normal cells, increases infiltration of cells from spinal cord tissue into the material implant and improves regeneration of nerves throughout the injured area," said author Stephanie Seidlits.

The researchers show how the pores improve efficiency of gene therapies administered locally to the injured tissues, which can further promote tissue regeneration.

Since many spinal cord injuries result from a contusion, the biomaterial implants need to be injected in or near the injured area without causing damage to any surrounding spared tissue. A major technical challenge has been fabricating scaffold materials with cell-scale pore sizes that are also injectable.

In the researchers' method, they injected beads of material through a small needle into the spinal cord, where the beads stick together to form a scaffold, where cells can crawl in the pore spaces between the beads. The researchers found inclusion of these larger cell-scale pores within biomaterial scaffolds improved cell infiltration, gene delivery, and tissue repair after spinal cord injury, compared to more conventional materials with nanoscale pores.

The researchers made the highly porous scaffolds using two different methods. One was simpler but created a more irregularly sized pore network. The second was more complicated but created a highly regular pore structure.

Even though both materials had the same average pore size and chemical composition, more regenerating nerves were found to infiltrate scaffolds with regularly shaped pores.

"These results inform how to maximize interfacing with the nervous system," said Seidlits. "This has potential applications not only for developing new therapies for brain and spinal cord repair but also for brain-machine interfaces, prosthetics, and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases."

More information: "Injectable, macroporous scaffolds for delivery of therapeutic genes to the injured spinal cord" APL Bioengineering, aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0035291

Provided by American Institute of Physics