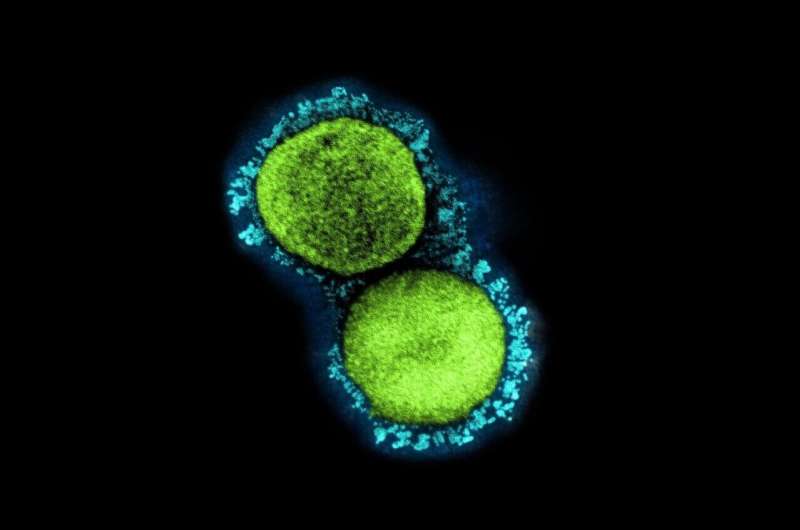

A transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (UK B.1.1.7 variant), isolated from a patient sample and cultivated in cell culture. Credit: NIAID

Larry Farber couldn't walk a mile last month without stopping three times to catch his breath, the aftereffect of a COVID-19 illness so severe that the 64-year-old was hospitalized twice and received powerful steroids and oxygen support to breathe.

Amy Crnecki wasn't hospitalized for COVID-19, but the 38-year-old still can't dance with her daughter without fear of crushing fatigue.

"I just want to be able to play outside with my kids," she said, "and play a game of basketball and not feel winded and feel like, 'I shouldn't have done that.' "

The two Minnesotans, diagnosed with COVID-19 during the same week in November, are part of a poorly understood group of people whose health has suffered long after infection and who could continue to struggle after the pandemic recedes. The number of COVID "long haulers" remains a mystery in a pandemic that otherwise has been one of the most measured, modeled and mapped events in human history.

To date, 7,296 people have died from COVID-19 in Minnesota and 594,427 have tested positive for the coronavirus that causes the disease. That includes 10 deaths and 805 infections that were reported Sunday. More than 2.7 million people—61.5% of the state's 16 and older population—have received at least a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

Little is known by comparison about the prevalence of long-term complications from COVID-19. This, in part, is because there is no agreed-upon definition of such cases and no easy methods of tracking them. State health officials said a better understanding is needed to plan for future medical needs. The end of Minnesota's mask-wearing mandate last week and the decline in infections signal a new phase in the pandemic—but not the end of its impact.

"We're starting to see that this pandemic is not one and done," said Richard Danila, deputy state epidemiologist. "We're seeing this tail at the end, where this pandemic is really unusual in that it's causing this rather substantial burden on individual people and on the population as a whole."

The Minnesota Department of Health activated an expert panel known as the Long-Term Surveillance for Chronic Disease and Injury Annex, which assesses lingering consequences of emergency or traumatic events. It provided advice following the 2017 gas explosion at Minnehaha Academy amid concerns that bystanders suffered brain trauma from the blast wave.

The group will work with federal authorities and researchers at the University of Minnesota and Mayo Clinic to define the breadth and scope of post-COVID illness in the state.

National and international studies have provided estimates. A report last month in the Journal of the American Medical Association found lingering symptoms eight months later in 10% of Swedish health-care workers who suffered mild COVID-19.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in April that 69% of people sought outpatient care one to six months after milder COVID illnesses that didn't require hospitalizations—often for related issues such as shortness of breath.

"Its going to be somewhere between 10 to 30%—definitely not a rare thing," said Dr. Greg Vanichkachorn, medical director of Mayo Clinic's COVID-19 Activity Rehabilitation Program. "This is something we're going to have to face."

It's easier to understand why someone as deeply injured as Farber might suffer lingering effects.

The retired policeman and former county commissioner from Zimmerman, Minn., didn't think he was that sick until his wife made him go to the emergency room just before Thanksgiving and he learned that his blood oxygen level was critically low.

Isolated at Northland Medical Center in Princeton, Farber feared death as he suffered an episode of shaking and convulsions one day, then struggled with malnutrition amid breathing difficulties. He lost 28 pounds during his first hospital stay.

"I kept just getting more [symptoms]," he said. "It was another new thing and another new thing."

More surprising has been the number of people with lingering problems who were never hospitalized. Vanichkachorn's study last week of the first 100 patients through the Mayo rehab program showed that only 25% had COVID-19 illnesses severe enough to need hospitalization.

Health systems such as M Health Fairview and North Memorial Health responded to the demand with post-COVID rehab programs—offering strength and therapy exercises to address chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, memory issues and foggy thinking.

Whether long-haul symptoms are caused by the lingering virus or the immune system's overreaction to infection is unclear, and nobody knows which patients will have them, said Dr. Tanya Melnik, a co-director of the M Health Fairview Adult Post-COVID Clinic.

"We don't have enough information to predict who can have it," she said.

The symptoms run from severe to comical, with Melnik recalling a patient who didn't regain her sense of taste and made what became known to her family as "COVID chili" because it was too spicy. Some of M Health's first rehab patients didn't even have positive COVID-19 tests, because tests were so scarce last spring.

The National Institutes of Health in February launched a $1 billion initiative to understand COVID-19 long haul symptoms, which it named Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). The U and Mayo have applied for some of the funding.

The duration of symptoms remains an open question that frustrates patients because they want to know when they will get better, said Jay Desai, the chronic health section manager for the Minnesota Department of Health who is leading the state annex review. "Some of these symptoms may last 30 days. Some of them may last 60 days. Some of them may start after 30 days."

Crnecki, a preschool worker from Savage, said COVID-19 never let up after her infection in November. Her blood oxygen levels were barely above what doctors said would require hospitalization. She isolated herself in her bedroom, where she struggled to eat and sleep amid chest pain and muscle aches. She helped her 8- and 5-year-old children virtually with their homework while they tossed notes of support into her room.

Weeks later, she still couldn't walk up steps without being exhausted—even though her blood oxygen levels appeared normal, which made it hard to convince doctors that something was wrong. The M Health rehab validated her symptoms and structured an exercise and strength program to boost her lung function.

She graduated from that three-month program in April but is continuing with therapy activities and took a leave from work. Word comprehension and processing is still slowed when talking, so she practices with word and story problems.

"I did a 5K on my Peloton this last week," she said, "which was huge for me."

Caleb Laurent can relate after nearly dying from a post-COVID illness in December, when the 16-year-old needed an ambulance ride in a blizzard and placement on a ventilator at St. Cloud Hospital to stop his lungs and heart from failing.

The Alexandria teenager suffered one of 84 known cases in Minnesota of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, which involves continued inflammation and damage to organs after COVID-19. The disorder is more clearly diagnosed and separate from other long-haul issues but is part of the broader universe of post-COVID impacts on Minnesota.

Laurent was back at Children's Hospital in Minneapolis last week for a treadmill test to monitor the impact on his heart function. He has regained strength and muscle with five months of rest and recovery. He hopes to return to football and wrestling and his old activities.

"His immune system turned on to fight the COVID but it didn't turn back off," said his father, Greg Laurent. "And it turned on his own organs and himself."

Farber, meanwhile, is getting impatient with his recovery, but has cycled off steroids and physical therapy and walks twice a day with less exhaustion. Seeing neighbors helps overcome the mental anguish from his hospitalizations, when his family couldn't be with him.

Farber cooked Thanksgiving dinner for his family in March to make up for missing the holiday, when he could eat only crackers and gelatin.

"When it's all said and done, it's going to be close to a year to recover," he said. "It's frustrating. I thought summer would be here and I should be better by then, but there is nothing about this disease that is normal. It's a vicious disease."

©2021 StarTribune.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.