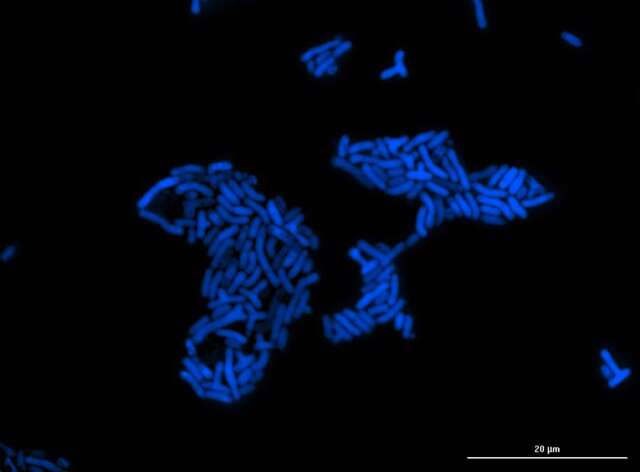

A microcolony of Methylorubrum extorquens. Credit: Nkrumah Grant

Bacteria called methylotrophs can use methane and methanol as fuel; in doing so, they produce large amounts of formaldehyde during growth, but until recently no one knew how they detected and responded to this toxic compound. Publishing on 26th May, 2021 in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology, Christopher Marx of the University of Idaho and colleagues describe their discovery of a novel formaldehyde sensor in the bacterium Methylorubrum extorquens, and other methylotrophs.

Some may remember the pungent smell of this toxic chemical from high school dissections of formaldehyde-preserved animals. From bacteria to humans, all organisms produce at least a little formaldehyde as a byproduct of their normal metabolic processes. Methylotrophs, however, make substantially higher amounts of formaldehyde while breaking down certain one-carbon compounds, like methane and methanol, which they use as a source of both carbon and energy.

Marx and his team found the new formaldehyde sensor by growing a methylotroph on increasingly higher formaldehyde concentrations. They sequenced the genomes of bacteria that had evolved to tolerate excess formaldehyde and saw mutations in a previously unknown gene they named efgA, for "enhanced formaldehyde growth." They found that this gene occurs almost exclusively in the genomes of methylotrophs, and that the EfgA protein the gene encodes can detect formaldehyde and quickly stop bacterial growth when levels of the toxic chemical get too high. The researchers also demonstrated that inserting the efgA gene into a non-methylotroph bacterium, E. coli, allowed it to survive at higher-than-normal formaldehyde levels.

Previously, scientists had identified enzymes in all domains of life that detoxify formaldehyde. But this is the first protein sensor described in methylotrophs that can detect formaldehyde and halt growth to prevent cell damage, all without involving detoxifying enzymes. The new discovery may have applications in biotechnology; bacteria engineered to withstand high formaldehyde concentrations with the efgA gene could potentially produce pharmaceuticals and other valuable compounds while growing on methanol, a readily available industrial material.

Dr. Marx notes, "This work has been a surprising outgrowth of a simple question: what does it take for cells to grow directly on formaldehyde? Remarkably, they needed to break a sensor system rather than crank up detoxification. Work is ongoing to further understand the binding specificity of EfgA and homologous proteins as well as to try to move from a hypothetical link between EfgA and translation suggested in several ways in this paper to establishing a direct protein-protein interaction."

More information: Bazurto JV, Nayak DD, Ticak T, Davlieva M, Lee JA, Hellenbrand CN, et al. (2021) EfgA is a conserved formaldehyde sensor that leads to bacterial growth arrest in response to elevated formaldehyde. PLoS Biol 19(5): e3001208. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001208

Journal information: PLoS Biology , PLoS ONE

Provided by Public Library of Science