China becomes the 40th territory certified malaria-free by the WHO.

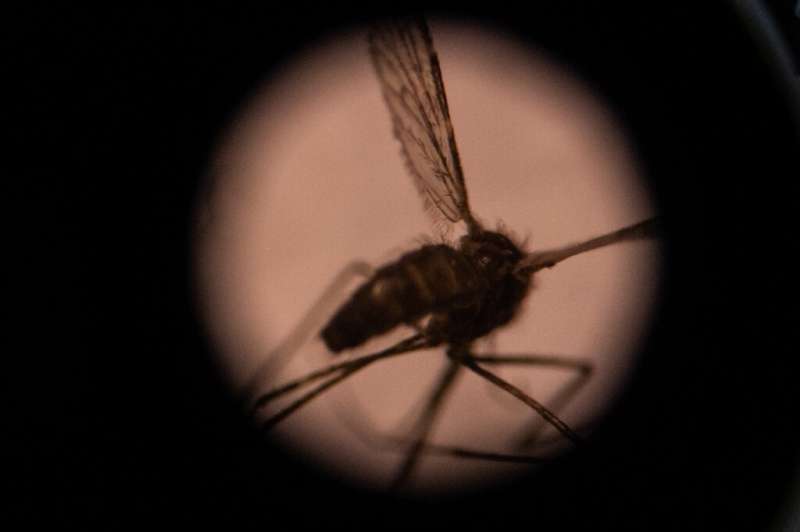

China was certified as malaria-free on Wednesday by the World Health Organization, following a 70-year effort to eradicate the mosquito-borne disease.

The country reported 30 million cases of the infectious disease annually in the 1940s but has now gone four consecutive years without an indigenous case.

"We congratulate the people of China on ridding the country of malaria," said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

"Their success was hard-earned and came only after decades of targeted and sustained action. With this announcement, China joins the growing number of countries that are showing the world that a malaria-free future is a viable goal."

Countries that have achieved at least three consecutive years of zero indigenous cases can apply for WHO certification of their malaria-free status. They must present rigorous evidence—and demonstrate the capacity to prevent transmission re-emerging.

Beijing, which is in the middle of a propaganda push ahead of celebrations for the 100th anniversary of the founding of its ruling Communist Party this week, hailed the WHO's certification as a "great achievement for China's human rights cause".

"The CCP and the Chinese government have always prioritised safeguarding people's health, safety and prosperity," said foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin at a routine briefing in Beijing.

"Eliminating malaria is a great contribution by China to human health and global human rights progress."

China becomes the 40th territory certified malaria-free by the Geneva-based WHO.

The last countries to gain the status were El Salvador (2021), Algeria and Argentina (2019), and Paraguay and Uzbekistan (2018).

There is a separate list of 61 countries where malaria never existed, or disappeared without specific measures.

China is also the first country in the WHO's Western Pacific region to be awarded a malaria-free certification in more than three decades.

The WHO's World Malaria Report 2020 warned global progress against the disease was plateauing, particularly in African countries bearing the brunt of cases and deaths.

In 2019 the global tally of malaria cases was estimated at 229 million—a figure that has been at the same level for the past four years.

'Outside the box'

In the 1950s, Beijing started working out where malaria was spreading and began to combat it with preventative anti-malarial medicines, said the WHO.

The country reduced mosquito breeding grounds and stepped up spraying insecticide in homes.

While searching for new malaria treatments in the 1970s, China discovered artemisinin—the core compound of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), which are the most effective antimalarial drugs available.

In the 1980s, China was among the first countries to extensively test the use of insecticide-treated nets to prevent malaria. By 1988, more than 2.4 million had been distributed nationwide.

By the end of 1990, the number of malaria cases in China had plummeted to 117,000, and deaths had been cut by 95 percent.

"China's ability to think outside the box served the country well in its own response to malaria, and also had a significant ripple effect globally," said Pedro Alonso, director of the WHO's global malaria programme.

Southern border surveillance

From 2003, China stepped up efforts across the board that brought annual case numbers down to around 5,000 within 10 years.

After four consecutive years of zero indigenous cases, China applied for WHO certification in 2020.

Experts travelled to China in May this year to verify its malaria-free status—and its plans to prevent the disease from coming back.

The risk of imported cases remains a concern, not only among people returning from sub-Saharan Africa and other malaria-hit regions, but also in the southern Yunnan province, which borders Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, all struggling with the disease.

China has stepped up its malaria surveillance in at-risk zones in a bid to prevent the disease re-emerging, said the WHO.

© 2021 AFP