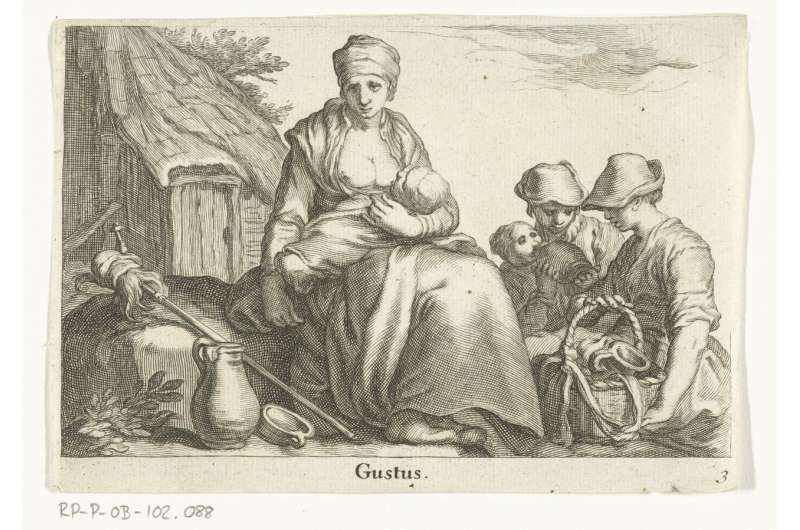

A farmer’s wife breastfeeds her baby while two other women give water to a child from a pitcher. From The Five Senses Series by Fredrick Bloemaert, after Abraham Bloemaert, 1632-1670. Credit: Frederick Bloemaert (printmaker), Abraham Bloemaert (designer), Nicolaes Visscher (I) (publisher), image from Rijks Museum, Public Domain (creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/)

A 19th century rural Dutch village had unusually low rates of breastfeeding, likely because mothers were busy working, according to a study published April 13, 2022 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Andrea L. Waters-Rist of the University of Western Ontario and colleagues.

Artificial feeding of infants, as opposed to breastfeeding, is considered a fairly modern practice, much rarer before the advent of commercially available alternatives to breast milk. However, studies of past populations in Europe have found that breastfeeding practices can vary significantly with regional cultural variation. In this study, researchers examine a 19th century dairy farming rural village in the Netherlands to explore factors linked to lower rates of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding leaves its mark in the bones of infants in the form of altered ratios of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes. In this study, researchers tested isotopic signatures in the remains of 277 individuals, including nearly 90 infants and children, from Beemster, North Holland. They found little to no evidence of breastfeeding, surprising given that this community exhibits features commonly associated with breastfeeding communities of the time, such as a Protestant population of moderate socioeconomic status, and mothers commonly working in or near the home.

Since other evidence indicates that mothers in 19th century Beemster were commonly working as dairy farmers, the researchers suspect that a high workload and a ready supply of cow's milk as an alternative infant food source were important factors contributing to these low rates of breastfeeding. At a few urban archaeological sites, mothers who worked long factory shifts have been found to have low rates of breastfeeding, but a similar phenomenon has not been found in a rural population until now. Future study on more sites will help elucidate how regional cultural practices impacted rates of breastfeeding over time, and in turn, how these factors have impacted infant health over recent centuries.

The authors add: "Artificial feeding of infants is not just a recent phenomenon. Female dairy farmers from 19th century Netherlands chose to not breastfeed, or to wean their infants at a young age, because of the availability of fresh cow's milk and high demands on female labor."

More information: Isotopic reconstruction of short to absent breastfeeding in a 19th century rural Dutch community, PLoS ONE (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265821

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by Public Library of Science