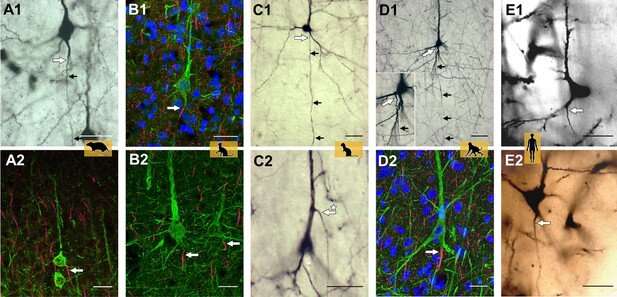

Representative axon carrying dendrite (AcD) neurons. (A1, A2) From rat visual cortex (biocytin, immunofluorescence); (B1, B2) cat visual cortex (immunofluorescence); (C1, C2) ferret visual cortex (biocytin); (D1, D2) macaque premotor cortex (biocytin, immunofluorescence), the inset shows the axon origin at higher magnification; (E1, E2) human auditory cortex (Golgi method; D2 is a montage of two photos). Apical AcDs (asterisk in C2) were rare, less than 10 were detected among the neurons assessed in adult rat, ferret, and macaque, and none in our human material. In all cases, the axon immediately bent down toward the white matter. Axon origins are marked by large arrows, small arrows indicate the course of biocytin-labeled axons. Scale bars 25 µm. Credit: eLife (2022). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.76101

Researchers from the research group Developmental Neurobiology at Ruhr-Universität Bochum around Professor Petra Wahle, in collaboration with partners from Mannheim and Jülich, Germany, and Linz, Austria, and La Laguna, Spain, have shown that primates and non-primates differ in an important aspect of their architecture: the origin of the axon, which is the process responsible for the transmission of electrical signals called action potentials. Results were published 20 April 2022 in the Journal eLife.

Axons can emerge from dendrites

Until now, it was considered textbook knowledge that the axon always, with few exceptions, arises from the cell body of a neuron. However, it may also originate from dendrites, which serve to collect and integrate the incoming synaptic signals. These are called axon-carrying dendrites.

"A unique aspect of the project is that the team worked with archived tissue and slide preparations, which included material that has been used for years to teach students," explains Petra Wahle. In addition, a range of species was studied, including rodents (mouse, rat), ungulates (pig), carnivores (cat, ferret), and macaque and human of the zoological order primates. The use of five staining methods and assessment of more than 34,000 neurons led the group to conclude that there is a species difference between non-primates and primates. Excitatory pyramidal neurons in particular of the outer layers II and III of the cerebral cortex of primates has clearly fewer axon-carrying dendrites than pyramidal neurons of non-primates.

Further, quantitative differences in the proportion of axon-carrying dendrite cells were found within the species cat and human for inhibitory interneurons. No quantitative differences were observed when comparing in macaque cortical areas with primary sensory and higher brain functions. High-resolution microscopy was of particular importance, as Petra Wahle describes: "This allowed the detection of axonal origins accurately tracked at the micrometer level, which is sometimes not so easy with conventional light microscopy."

The video shows a neuron (marked in green) of a macaque from which an axon (in red) arises from the dendrite. The cell nuclei can be seen in blue. Credit: Ruhr-Universitaet-Bochum

Evolutionary advantage still enigmatic

Little is known on the function of axon-carrying dendrites. Usually, a neuron integrates excitatory inputs arriving at the dendrites with inhibitory inputs, a process termed somatodendritic integration. The neuron then decides if inputs are strong enough and important enough to be transmitted via action potentials to other neurons and brain areas. Axon-carrying dendrites are considered privileged because depolarizing inputs to these dendrites are able to evoke action potentials directly without involvement of somatic integration and somatic inhibition. Why this species difference has evolved, and the potential advantage it may have for the neocortical information processing in primates, is as yet unknown.

More information: Petra Wahle et al, Neocortical pyramidal neurons with axons emerging from dendrites are frequent in non-primates, but rare in monkey and human, eLife (2022). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.76101

Journal information: eLife

Provided by Ruhr-Universitaet-Bochum