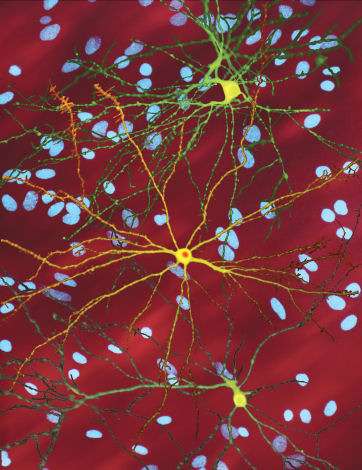

A montage of three images of single striatal neurons transfected with a disease-associated version of huntingtin, the protein that causes Huntington's disease. Nuclei of untransfected neurons are seen in the background (blue). The neuron in the center (yellow) contains an abnormal intracellular accumulation of huntingtin called an inclusion body (orange). Credit: Wikipedia/ Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

In a new University at Buffalo-led study, scientists propose a new role for the huntingtin protein (HTT), which causes Huntington's disease when mutated.

A team led by UB biologist Shermali Gunawardena has been investigating HTT and its basic functions in cells called neurons for a long time. The scientists previously found that in its unmutated form, HTT regularly travels along neuronal highways called axons, both toward and away from the cell's nucleus.

A new study builds on this past work, detailing a previously unknown role for HTT in cellular compartments that move in one direction, toward the nucleus. The research suggests that HTT is involved in neuronal injury and regeneration—a novel discovery, says Gunawardena, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences in the UB College of Arts and Sciences.

"We are finding that HTT is packaged in different types of moving cargo within cells, and that it's involved in so many processes. This suggests that it's really a key protein in controlling a lot of cellular pathways that are important in cell survival. It doesn't have just a single role, so it's a very complex protein to understand," Gunawardena says.

Credit: University at Buffalo

In the new paper, "We show that the huntingtin protein is involved during neuronal injury," Gunawardena says. "When neurons in fruit fly larvae were injured, we see that HTT moves from the injury site to the cell body. It likely carries components that are necessary for survival of the neuron toward the cell body, where the nucleus is and where proteins are made."

Experiments suggest that this HTT package may carry signaling molecules that "are essential for activating the production of proteins needed for neuron regeneration," Gunawardena says. She adds that, "future studies will be needed to determine the identity of the molecules involved in the regeneration."

The study was published in Autophagy.

"While many studies investigate disease mechanisms of HTT in Huntington's disease, here we focused on investigating basic roles of HTT in neurons. By combining a variety of laboratory techniques, we were able to model a novel mechanism in which HTT helps injury signals transport back to the cell body after axonal injury," says first author TJ Krzystek, Ph.D., who worked on the study as a Ph.D. student in biological sciences at UB and is now a postdoctoral research fellow at Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School and the National Institutes of Health.

"We have known for decades that neurons of the central nervous system exhibit poor regeneration following axonal injury," Krzystek says. "By investigating more unconventional proteins and pathways in the context of axonal regeneration, we can learn more about the potential causes of this problem with the goal of eventually opening up possibilities for finding and validating future candidates to target new therapies."

More information: Thomas J. Krzystek et al, HTT (huntingtin) and RAB7 co-migrate retrogradely on a signaling LAMP1-containing late endosome during axonal injury, Autophagy (2022). DOI: 10.1080/15548627.2022.2119351

Provided by University at Buffalo