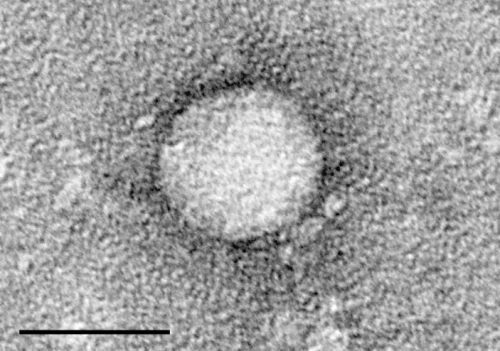

Electron micrographs of hepatitis C virus purified from cell culture. Scale bar is 50 nanometers. Credit: Center for the Study of Hepatitis C, The Rockefeller University.

Too many Americans are missing out on a cure for hepatitis C, and a study underway in a hard-hit corner of Kentucky is exploring a simple way to start changing that.

The key: On-the-spot diagnosis to replace today's multiple-step testing.

In about an hour and with just a finger-prick of blood, researchers can tell some of the toughest-to-treat patients—people who inject drugs—they have hepatitis C and hand over potentially life-saving medication.

Waiting for standard tests "even one or two days for someone who's actively using drugs, we can lose touch with them," said Jennifer Havens of the University of Kentucky, who's leading the study in rural Perry County. To start treatment right away "that's huge, absolutely huge."

Single-visit hepatitis C diagnosis already is offered in other countries, and now the White House wants to make it a priority here.

"It's frankly an embarrassment" that the U.S. doesn't have such an option, said Jeffrey Weiss of New York's Mount Sinai health system, who works with a community hepatitis C outreach program. "We have many people we've tested and want to give their results to and can't find them."

At least 2.4 million Americans are estimated to have hepatitis C, a virus that silently attacks the liver, leading to cancer or the need for an organ transplant. It leads to more than 14,000 deaths a year. That's even though a daily pill taken for two to three months could cure nearly everyone with few side effects.

Yet in the U.S., more than 40% of people with hepatitis C don't know they're infected. Fewer than 1 in 3 insured patients who are diagnosed go on to get timely treatment. And new infections are surging among younger adults who share drug needles.

"This is a travesty," said Dr. Francis Collins, the former National Institutes of Health director who's now a White House adviser devising a new national strategy to tackle hepatitis C.

Most likely to fall through the cracks are "people in tough times"—those who inject drugs, are uninsured or on Medicaid, or are homeless or incarcerated—who can't navigate what Collins calls the "clunky" diagnosis process and other barriers to the pricey pills.

For the country not to address those inequities "feels like a moral failing," Collins told The Associated Press.

All American adults are urged to be screened for hepatitis C, a blood test that simply tells if someone's been exposed. Because the immune system sometimes clears the virus, anyone found positive then must get a different kind of blood test to confirm they're still infected. If so, they return again to be prescribed treatment.

But in Britain, Australia and parts of Europe, people can get on-the-spot hepatitis C diagnostic testing, using a machine made by California-based Cepheid Inc. It's sort of a lab-in-a-box that's especially useful for mobile clinics and needle-exchange programs where hard-to-reach populations can be tested and start treatment in a single visit.

This kind of technology isn't new—Cepheid's version already is used in the U.S. to do quick tests for COVID-19, flu and certain bacterial infections, among other things. But test manufacturers haven't gone through the complex U.S. regulatory process for approval to diagnose hepatitis C.

Chief scientific officer David Persing said Cepheid hopes to take that step next year—using a new pandemic-era program that would streamline the evidence needed for clearance of an easy-access, test-and-treat option.

Testing isn't the only hurdle. A full course of hepatitis C pills costs about $24,000—much less than when they first hit the market but enough that many states still restrict which Medicaid patients are treated. Some require proof of sobriety to get care, stalling efforts to stop current spread of the virus among people who inject drugs. Others add red-tape "prior authorization" requirements and some order consultations with liver specialists, according to the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable and Harvard researchers.

Pilot programs have attempted to overcome such barriers. For example, Louisiana negotiated a yearly flat-fee for unlimited doses of hepatitis C medication for Medicaid patients and state prisoners. It got off to a strong start but was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and hasn't recovered: Louisiana has treated about 12,600 such patients since 2019, out of an estimated 40,000 in need.

The scope of Collins' plans for a national hepatitis program will depend on how much funding the Biden administration comes up with—but faster, easier testing is a priority.

In Perry County, Kentucky, Havens' team uses the Cepheid test in an NIH-funded study on how to improve care for hepatitis C patients struggling with addiction. While potential study participants await their test results, researchers teach them about the virus and offer other health services.

"Even if they test negative, they still got something" useful from the visit, Havens said.

© 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.