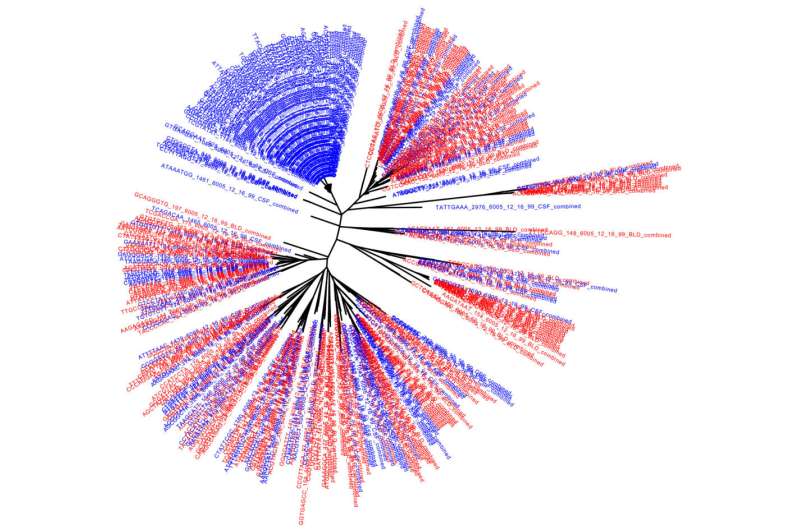

Rebound DNA sequences from the blood (red) and the CSF (blue). Credit: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

When people living with HIV take antiviral therapy (ART), their viral loads are driven so low that a standard blood test cannot detect the virus. However, once ART is stopped, detectable HIV re-emerges with new cells getting infected. This is called "rebound" virus, and the cells that release the virus to re-ignite the infection come from a small population of HIV-infected CD4+ T cells that had remained dormant in blood and lymph tissue while individuals were on ART.

It's a problem called latency, and overcoming it remains a major goal for researchers trying to create curative therapies for HIV—the special focus of the UNC HIV Cure Center.

Now, scientists led by virologist Ron Swanstrom, Ph.D., Director of the UNC Center for AIDS Research and the Charles P. Postelle, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry & Biophysics at the UNC School of Medicine, describe another layer to the challenge of HIV latency and published their work in Nature Microbiology.

Swanstrom and colleagues, with collaborators at UCSF, Yale, the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and others, provide indirect evidence for the existence of a distinct latent reservoir of CD4+ T cells in the central nervous system (CNS). They accomplished this by analyzing rebound virus in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) during the period when people had just stopped taking ART.

"Our analysis of rebound virus suggests latently infected T cells in the CNS are separate from the latent reservoir in the blood," said Swanstrom, senior author of the study. "Our analysis allows us to infer the presence of a distinct pool of latently infected cells in the CNS waiting to reinitiate infection once ART is interrupted."

The researchers compared the genetic sequences of rebound virus particles when ART was discontinued in 11 human participants. This approach allowed the scientists to assess the similarities between viral populations in the blood and CSF to determine whether they were part of a common latent reservoir. In many cases, the viral populations were not the same, which suggested they can represent different populations of latently infected cells.

The researchers also studied details of viral replication to determine if rebound virus had been selected for replication in CD4+ T cells—the primary home of the virus—or had evolved to replicate in central nervous system myeloid cells, such as macrophages and microglia. All rebound viruses tested were adapted to growth in T cells. For several participants, the researchers also compared viral populations in blood and CSF before ART initiation and after ART was stopped.

These experiments provide further evidence that HIV-infected CD4+ T cells can cross over from blood into the CNS, but also that some latently infected cells may be resident in the CNS during therapy. Any curative therapy would need to activate this dormant reservoir, as well as the latent reservoir in the blood and lymph tissue.

More information: Rebound virus in the cerebrospinal fluid reveals a possible HIV-1 reservoir, Nature Microbiology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-022-01309-3

Journal information: Nature Microbiology