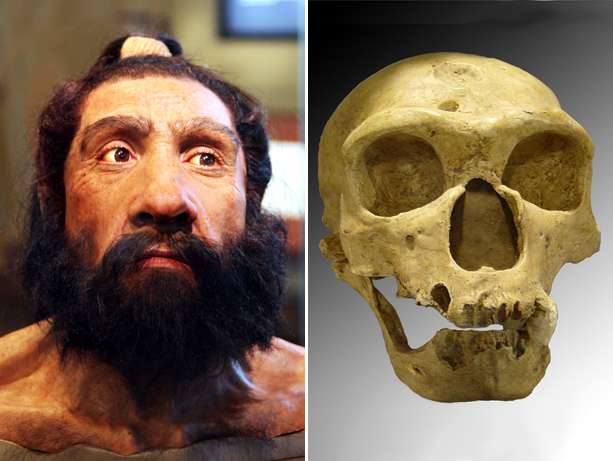

The reconstruction of a head of a Neanderthal man, at left, and a Neanderthal skull. One gene identified by UW Medicine and other researchers may be the first identified that distinguishes humans from the Neanderthals. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (Tim Evanson, left photo, and luna04)

A structure that represents the biggest known genetic difference between humans and Neanderthals also predisposes humans to autism.

An international team of researchers led by UW Medicine genome scientist Evan Eichler published the findings today in Nature.

The structure involves a segment of DNA on chromosome 16 that contains 28 genes. This segment is flanked by blocks of DNA whose sequences repeat over and over.

Such stretches of duplicated DNA, called copy-number variants, are common in the human genome and often contain multiple copies of genes. Although most copy-number variants seem to have no adverse effect on health, some have been linked to disease.

However, when both strands of a segment of DNA are flanked by highly identical sequences, they can be susceptible to large copy-number differences, including deletion, duplication and other changes, during the process of cell division. In this case, deletion, which causes the loss of the segment's 28 genes, results in autism.

In the new study, researchers determined that this structure, located at a region on chromosome 16 designated 16p11.2, first appeared in our ancestral genome about 280,000 years ago, shortly before modern humans, Homo sapiens, emerged. This organization is not seen in any other primate – not chimps, gorillas, orangutans nor the genomes of our closest relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans. Yet today, despite the fact that the structure is a relatively new genetic change, it is found in genomes of humans the world over.

Forensic reconstruction of a Homo neanderthalensis. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Cicero Moraes

"Most duplications in our genome are millions of years old, and the speed at which this structure transformed our genome is unprecedented," said co-author Eichler, a professor of genome sciences and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "The wide and rapid distribution of these copy-number variants suggests the genes within the repetitive sections confer benefit that outweigh the disadvantages that come with the increased risk of autism in some offspring, should deletion occur."

Copy-number variants may play an important role in human evolution because, as a species, we are relatively uniform genetically.

"If you took two chimps out of the wild, they would have twice as many genetic differences in their genomes than you would see between two humans. And orangutans have three times as many differences. Having these structures means we have a way to radically restructure our genome over a very short time frame, bringing about changes that might otherwise take hundreds of millions of years of evolution to acquire – but at the cost of an increased risk of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders," he said.

One benefit of copy-number variants: They contain multiple copies of genes that can mutate and acquire new, potentially useful functions.

Credit: University of Washington

Of particular interest to the researchers was a gene in the copy-number variants at 16p11.2 called BOLA2, multiple copies of which were found in both flanking regions. The BOLA2 protein in human cells appears to form a complex with another protein, called glutaredoxin 3, that allows the cells to capture iron more efficiently and make it available to proteins that require it. This effect appears to be most pronounced early in cell development.

"This ability to help humans to acquire and use this essential element early in life might confer a significant enough benefit to outweigh the risk of having some offspring with autism," Eichler said.

In addition to BOLA2, the mutations within the copy number variant regions appears to have created new protein formed by fusing two regions of the BOLA2 gene with three regions of another gene. This new gene may be the first completely new gene that distinguishes humans from our Neanderthal and ancient hominin cousins, Eichler said. Exactly what role the new protein it creates plays remains unknown. "We're going to work with other research teams to find out what it does but so far we haven't a clue."

More information: Xander Nuttle et al. Emergence of a Homo sapiens-specific gene family and chromosome 16p11.2 CNV susceptibility, Nature (2016). DOI: 10.1038/nature19075

Journal information: Nature

Provided by University of Washington