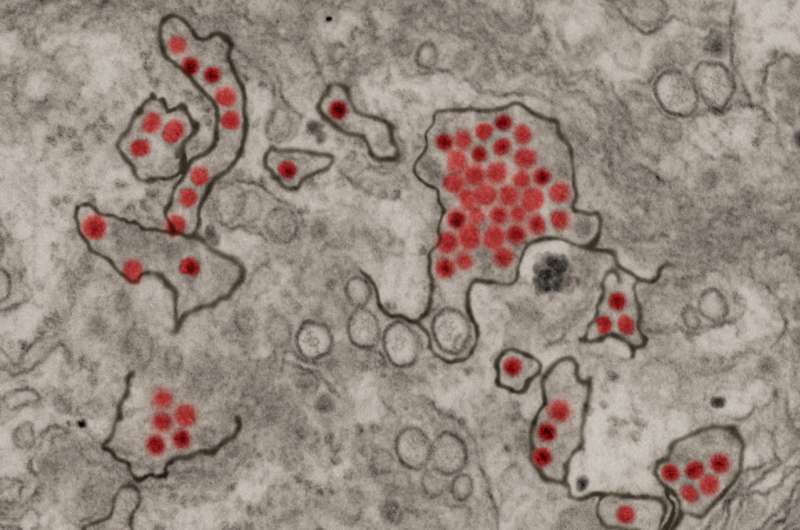

Zika virus particles (red) shown in African green monkey kidney cells. Credit: NIAID

Two years ago, the world was gripped in Zika panic as the mosquito-borne virus infected millions and spread across 80 countries. Officials declared a global health emergency and tourists canceled their tropical vacations. Thousands of babies were born with devastating birth defects after their mothers were infected in pregnancy.

Today, public health priorities have shifted as the virus fades. In hard-hit Brazil, where some athletes skipped the 2016 Summer Olympics out of Zika fears, confirmed cases dropped from 206,000 that year to fewer than 14,000 in 2017, all before April.

Cases of the virus in the U.S. dropped from 5,102 in 2016 to 385 last year—all but three acquired while traveling to tropical areas.

Last month, the Missouri health department said it will stop testing most pregnant women who have traveled to Zika-affected areas. Clinical trials of a Zika vaccine at St. Louis University will not move into a second phase of testing after a drugmaker pulled funding.

Intensive mosquito control probably had an effect on Zika's presence. Travel warnings and personal precautions such as bug spray also helped. Most likely, a high enough percentage of people were infected across central and South America that a "herd immunity" developed, making it hard for the virus to continue its spread.

Still, "we are not finished with Zika," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

"Even though when you look at the number of infections, it's dramatically down, it doesn't mean they're going to stay down," Fauci said. "You've got to be careful when dealing with vector-borne diseases. They have a tendency to cycle in and out. It very well could come back."

Fauci said the federal government remains committed to getting its Zika vaccine to market, with testing in Puerto Rico and South America. He pointed to the record four months it took between sequencing the virus's DNA to testing vaccines as proof of the urgency.

At St. Louis University, 90 people entered a trial for another Zika vaccine. Early results released last month showed the vaccine had no significant safety concerns, and produced a favorable immune response in nearly all the volunteers.

But that trial has stalled, with no plans for a second phase of testing in Zika-affected areas after drugmaker Sanofi pulled funding, citing a combination of reduced virus activity and government budget cuts.

Dr. Sarah George, associate professor of infectious diseases, allergy, and immunology at St. Louis University, said the initial research will be useful because a vaccine can be ready for further testing if an outbreak occurs.

"That will happen. We just don't know when or where," she said.

It happened in summer 2016 in Miami, where federal health officials issued their first-ever medical travel warning in the U.S. The Zika outbreak in Florida infected nearly 300 people in 2016. Just two people were infected in Florida in 2017. Last week, state health officials closed their Zika information hotline.

The World Health Organization counted 12 outbreaks worldwide in 2015, 22 in 2016 and just one in early 2017—three cases in India. The health agency hasn't issued a Zika situation report since March 2017.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently deactivated its emergency response system for Zika that was launched in January 2016.

Mosquito-borne viruses are notoriously tricky to predict, and experts say it's premature to dismiss the threat entirely. There is still much to be learned about Zika, which seems to be the only virus of its type to cross the placental barrier and stunt the brain development of the fetus. It is also unusual because it can be spread through sexual contact.

Even if Zika never returns at the same levels, thousands of children face lifelong disabilities. A study of Brazilian babies diagnosed with Zika at birth in 2015 and 2016 shows that most experience seizures, can't sit up or walk and have hearing and vision problems.

The future of Zika could look like the pattern of mosquito-borne West Nile virus, which hit highs 9,862 cases in the U.S. in 2003 and hasn't reached those numbers since. Or it could be more like dengue virus, with four subtypes that reliably infect more than 1 million people each year in the Southern Hemisphere.

There are some other clues about Zika's path based on its emergence in the South Pacific. About 75 to 80 percent of people were estimated to have been infected in 2013 and 2014 on some islands in French Polynesia, where the virus has since been virtually eradicated. Once people are infected, they are thought to be immune for life. If a large enough percentage of the population has immunity, the virus can't take hold.

"After a wave of infection comes through, there are very few susceptible people left to infect in subsequent years," said Dr. Steven Lawrence, infectious disease specialist at Washington University. "It may be once you weather the initial storm of the first year or two, then it becomes a less prominent problem in future years."

Although mosquito-borne viruses are not known to mutate readily, much about Zika remains a mystery. It could make the leap from tropical mosquito species to others that are more common in the U.S., Lawrence said.

The Missouri State Public Health Laboratory still recommends and provides Zika testing for anyone who may have been exposed to the virus and went on to develop symptoms, which include fever, rash and joint pain. Pregnant women are still advised to avoid travel to tropical areas.

"We can't totally write it off yet," Lawrence said. "It's still a potential problem for people traveling. There is always the potential for changes in the virus. I don't think the story is over."

©2018 St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.