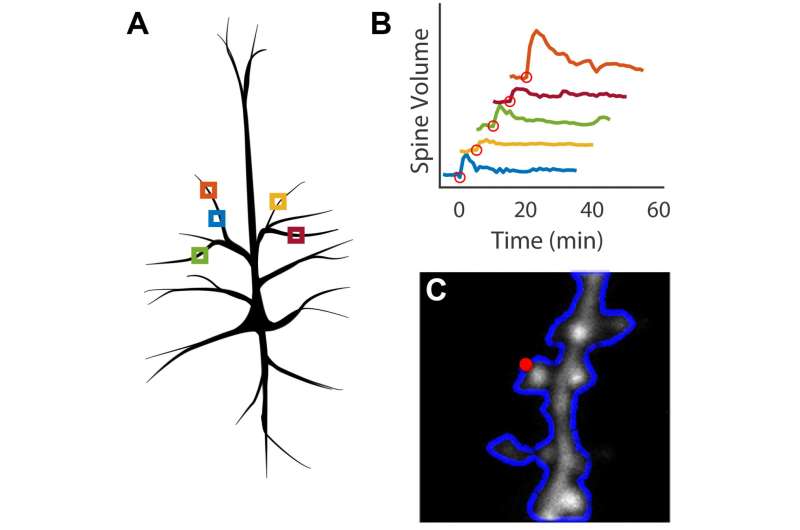

A: Individual imaging locations are identified on a single cell. B: Parallel stimulation of dendritic spines results in changes in spine volume. C: Optimal locations for photostimulation are automatically identified on each spine prior to stimulation. Credit: Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience

When humans and animals learn and form memories, the physical structures of their brain cells change. Specifically, small protrusions called dendritic spines, which receive signals from other neurons, can grow and change shape indefinitely in response to stimulation. Scientists at Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (MPFI) have observed this process, known as long-term structural plasticity, in individual spines, but doing so requires substantial time and effort. A new technique, developed by MPFI researchers, automates the process to make observing and quantifying this growth far more efficient. The open-source method is available to any scientist hoping to image plasticity as it happens in dendritic spines using Scanimage. The work was published in January 2016 in the Public Library of Science journal, PLOS ONE.

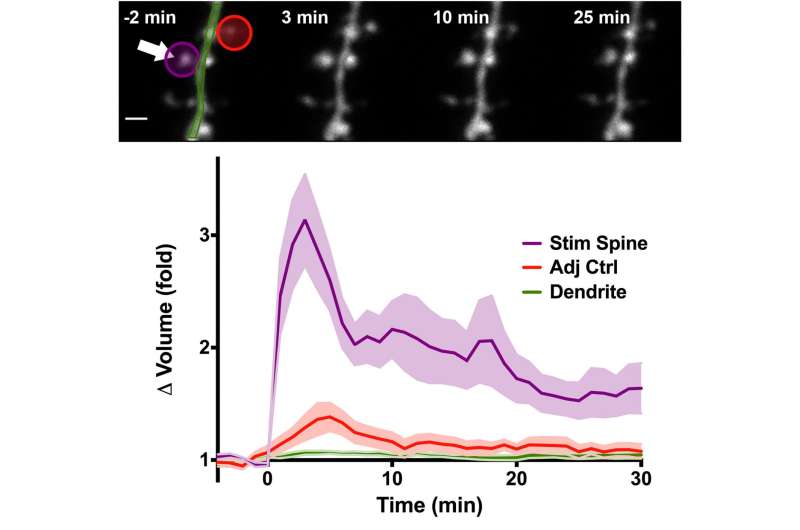

Scientists working in Ryohei Yasuda's laboratory at MPFI are working to understand how proteins facilitate the plasticity of dendritic spines, the biological basis of learning and memory. They use 2-photon microscopy, an advanced technique for live-cell imaging, and glutamate uncaging, a technique that can induce plasticity in individual spines of interest using light. This is a meticulous process, wherein a scientist must continually focus the microscope on a single dendritic spine over an extended period, often an hour or longer. Michael Smirnov, Ph.D., Post-doctoral researcher at MPFI, developed a software that allows the computer to automatically track, image, and stimulate up to five dendritic spines at a time. "We can collect the data and figure out the proteins responsible much quicker with this [program] because we can run much more robust experiments," said Smirnov. In addition to increasing productivity, the ability to stimulate and image multiple spines in parallel greatly decreases the cost of running these experiments.

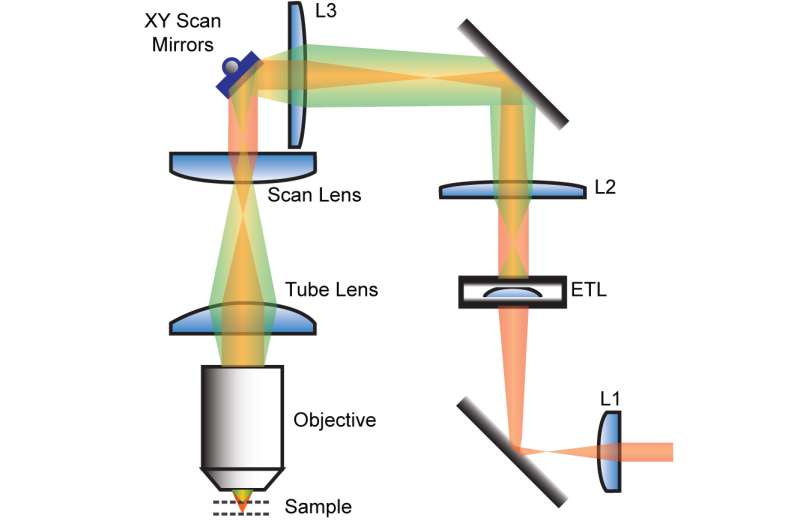

The software is a MATLAB-based module built for Scanimage, a program already commonly used in life science laboratories. It includes an electrically tunable lens in combination with a drift correction algorithm. These aspects allow the program to identify and correct for sample movement to ensure that the microscope is consistently focused on the spines of interest throughout the duration of the experiment. The interface provides an inexpensive method for automating experiments that observe up to five dendritic spines at a time, as opposed to a single spine using existing methods.

An ETL in the excitation pathway shapes the incoming beam for remote focusing. Beam shape (red/green) is controlled by curvature of the ETL. L2 and L3 lenses are placed to conjugate the ETL to the back aperture of the objective lens. Credit: Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience

In contrast to previous open-sourced focusing programs, this one implements a highly capable and customizable focus and drift correction system to ensure that it can be used for a variety of biological applications. "The paper explains further modifications to make the process automated," said Smirnov. "It shares the open source code, so essentially, other people from other institutes can easily pick this up and use it for themselves."

(Top) Images of dendritic segments before and after glutamate uncaging. (Bottom) Graphical representation of the averaged volume change of the stimulated dendritic spine (purple), adjacent spine (red), and dendrite (green) following glutamate uncaging. Credit: Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience

More information: Michael S. Smirnov et al, Automated Remote Focusing, Drift Correction, and Photostimulation to Evaluate Structural Plasticity in Dendritic Spines, PLOS ONE (2017). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170586

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience