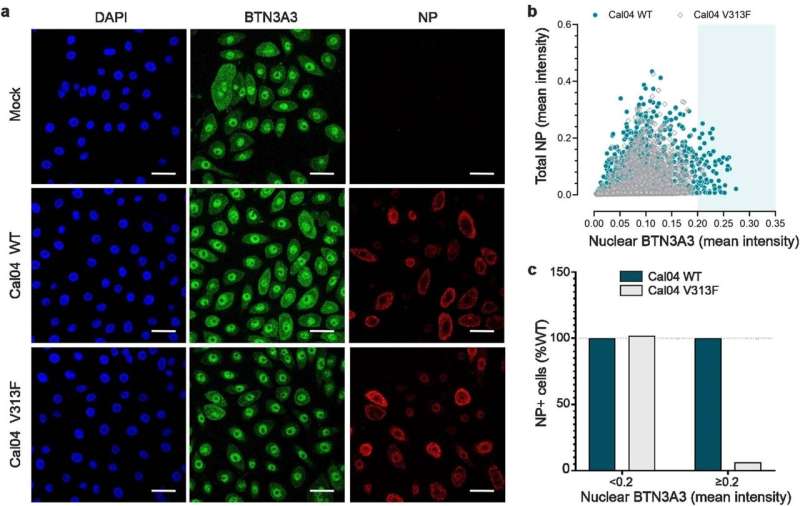

Correlation between NP signal and nuclear BTN3A3. a, Representative images of confocal microscopy of hBEC3-KT cells infected with Cal04WT or Cal04 NP V313F at MOI 3. Six hours post infection, cells were immunostained with NP (red) and BTN3A3 (green). DAPI staining (blue) was used as a nuclear marker. Scale bar = 35µm. b, Images from >3500 cells from four independent experiments performed as in (a) were used to quantify total NP and nuclear BTN3A3 for Cal04 WT and Cal04 NP V313F. c, Values from b were stratified based on nuclear BTN3A3 intensity (<0.2 or ≥0.2). Data represents relative abundance of total infected cells present in each of the two nuclear BTN3A3 intensities ranges, taking values obtained with Cal04 WT as 100%. Credit: Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06261-8

A large team of medical researchers and virus specialists at the University of Glasgow working with several colleagues from the University of Edinburgh and one from Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie has discovered a human gene that prevents most avian flu variants from jumping to humans.

In their study, reported in the journal Nature, the group identified virus-killing properties associated with the BTN3A3 gene. Laura Graf and Peter Staeheli with the University of Freiburg, have published a News & Views piece in the same journal issue, outlining the work done by the team on this new effort.

The work involved six years of screening proteins for antiviral activity in cultured human cells. The researchers discovered that most avian virus attempts to jump to human cells were blocked by the activation of the BTN3A3 gene. Once activated, an immune response ensured that the virus could not get a foothold, preventing infection. They also found that the gene is not a variant—it is present in everyone and has been in our gene pool for approximately 40 million years. A closer look showed that when viruses are identified, the gene is activated in the lungs, nose and throat, the sites most likely to be transmission areas.

The researchers also note that throughout history, viruses that have jumped from birds or swine, setting off epidemics or pandemics, have shown resistance to the activation of the BTN3A3 gene. They also note that avian flu variants are constantly evolving, which means some variants that are blocked from jumping to humans today could evolve to be resistant, allowing for such jumps in the future. The research team showed this to be the case with a virus called H7N9 that developed resistance over the years 2011 to 2013. Thus far, the strain has infected 1,570 people and killed 616.

The research team suggests their findings could simplify future work involved in assessing risk from new strains of avian flu—upon first discovery, it can be tested to see whether or not it has resistance to the protection provided by the BTN3A3 gene.

More information: Rute Maria Pinto et al, BTN3A3 evasion promotes the zoonotic potential of influenza A viruses, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06261-8

Laura Graf et al, A human protein that holds bird flu viruses at bay, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-01942-w

Journal information: Nature

© 2023 Science X Network