Former inmate describes efforts to stay emotionally healthy after his release.

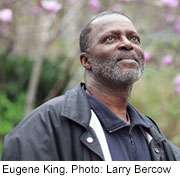

(HealthDay)—Eugene King ran away from home at the age of 16, the start of a lifelong pattern of drug abuse, crime and incarceration.

In retrospect, King said, he realizes he was using illicit drugs at least in part to self-medicate a variety of psychiatric conditions. But he also realizes that prison, with its lack of adequate medical treatment and what he called a generally abusive environment, only made his problems worse.

"It exacerbated [the mental illness] without a doubt," said King, now 62.

That King's mental health, already precarious, only worsened in prison is not an unusual story.

According to a recent study published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, the link between prison time and mental illness is a two-way street. Although many incarcerated people exhibit such problems as impulse control disorders—which normally first appear in childhood or adolescence—before they enter the correctional system, incarceration itself seems to cause major depression.

And this may help explain why so many inmates have trouble re-entering society when they are released, said the authors of the study.

"Prison made them depressed and that depression undermined their ability to re-enter—made it hard to find a job, hard to be motivated—and this is precisely the time they need to be motivated," said lead author Jason Schnittker, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. "We think that mood disorders are an important barrier to re-entry."

According to background information included in the study, about 16 million people—or 7.5 percent of the U.S. population—are felons or ex-felons.

Meanwhile, people in prison have up to six times the rate of significant mental illness as the general population, said Dr. Spencer Eth, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Eth also treats inmates at a local jail.

And although it has long been suspected that prison aggravates pre-existing psychiatric problems, experts have had trouble untangling this chicken-and-egg question, especially given that early childhood experiences are linked to both incarceration and mental illness.

For the study, Schnittker and his co-authors looked at a national database of nearly 5,700 men and women to assess both the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and any time spent in jail or prison.

Their conclusion? Incarceration was associated with a 45 percent increase in the risk of having depression.

The findings did have some limitations, namely that the authors couldn't control for all other factors that might affect the incidence of depression. And because it's so difficult to conduct studies in prison populations, it's possible that the data did not pick up on worsening of conditions other than depression, said Eth, who was not involved with the study.

The data were also at least a decade old, Eth said, even though "it's likely that if the study were to be repeated now there would be similar findings."

Although the study authors advocate for more treatment while people are in prison and before being let out onto the streets, in reality conditions in correctional facilities are often pitiful, said Eth, echoing King's sentiments.

"There's very, very little treatment available to people who are in jails and prisons. At most, it's medication, and for many conditions it's nothing at all. It's terrible," Eth said. "If you didn't have a serious mental illness going in, the conditions of jails and prisons are so deplorable, you'd have to be a hardy soul not to be depressed or worse."

Unfortunately, psychiatric treatment for ex-offenders "on the outside" is also limited, said JoAnne Page, president and CEO of the Fortune Society in New York City, which helps individuals re-enter society after prison.

"We couldn't get people into mental-health treatment in the community when it was available, and it's less available than it used to be," Page said.

In 2011, the Fortune Society, which already provided housing and other services for ex-offenders, opened its Better Living Center, which they said is the first agency in New York City to cater exclusively to individuals with a criminal history.

"Most of our people come to us after their release when we have a window of time," Page said. "There's a hopefulness that things could be different. It's a wonderful time to work with people if you give them a fighting chance."

It is through this Better Living Center that King got his chance. He now takes medication every day and sees a therapist weekly for bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

"I have access to excellent mental-health treatment now and I'm also mindful of the fact that there are [many] prison inmates who could benefit from the same level of care, or something close to it," King said. "Last week was my last day on parole. Over 25 years, I have been living on this cloud either in prison or on supervision. I am no longer. I am totally free."

More information: The U.S. Department of Justice has more on the mental-health problems of inmates.

Journal information: Journal of Health and Social Behavior

Health News Copyright © 2013 HealthDay. All rights reserved.