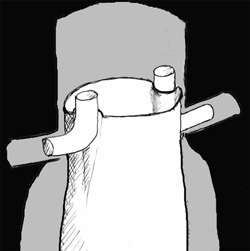

For complex aortic aneurysms, "snorkel" stents enable blood flow to branch arteries that otherwise would be obstructed by the main stent graft. Credit: Journal of Endovascular Therapy

Geraldine Vitullo lay anesthetized on an operating table in a Central Valley hospital. Her surgery had come to an unexpected stop. "I don't think I can proceed," the surgeon told Vitullo's husband.

The plan that day, in late 2011, had been to repair an aneurysm, a balloon-like bulge, in Vitullo's abdominal aorta using a synthetic graft. The small tube was to replace the section of weakened arterial wall to prevent it from bursting. But there was a problem: The aneurysm extended above branch arteries leading to her kidneys and intestines. This made the operation a much more complex challenge; the surgery to implant the graft might obstruct blood flow to her kidneys and potentially impair circulation to her intestines.

So after consulting with Vitullo's husband, the surgeon stopped the operation. He closed the long incision he had made in her abdomen. When she woke up, she discovered her predicament hadn't changed; the aneurysm remained, like a ticking time bomb. "I was a little upset, to say the least," said the 65-year-old grandmother and Visalia resident.

Then she heard about Jason Lee, MD, a vascular surgeon at Stanford Hospital & Clinics and associate professor of vascular surgery at the School of Medicine. Collaborating with Ronald Dalman, MD, the Dr. Walter C. Chidester Professor and chief of the Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Lee has helped to develop and streamline minimally invasive procedures for treating complex aortic aneurysms, such as Vitullo's, with a combination of stent grafts. He calls what he recommended for Vitullo "the snorkel technique" because it involves the use of stents that, when deployed into final position, look like snorkels. It is an endovascular procedure, meaning that the stents are inserted into blood vessels with a catheter through a small entry into an artery, rather thanthrough open surgery.

Lee is one of the world's most experienced physicians in endovascular repair of complex aneurysms using this technique, which involves placing the snorkel stents next to the main stent to create pathways for blood to reach branch arteries. Lee uses similar combinations of stents to treat aneurysms that sit alongside other aortic branch arteries ranging from the heart down to the legs.

Geraldine Vitullo, a resident of Visalia, had a complex abdominal aortic aneurysm that vascular surgeon Jason Lee treated using a minimally invasive technique that employs a combination of stents. Credit: Norbert von der Groeben

Abdominal aortic aneurysms, or AAAs, generally do not cause discomfort and often go unnoticed as they progressively enlarge. Vitullo's aneurysm was only detected by happenstance; it showed up on an X-ray taken to identify the source of an ache in her back.

Aneurysms are dangerous because they can rupture after a period of prolonged growth, causing large amounts of blood to leak into the abdominal cavity. When this happens, the overall mortality rate is about 50 percent even if the patient makes it to the operating room.

"Ruptured AAAs are highly associated with death even when treated appropriately, so early diagnosis prior to rupture and prompt intervention at the appropriate size are necessary to improve mortality from aneurysms," said Lee, who is also director of endovascular surgery at Stanford Hospital.

AAAs are five times more common in men than women. Incidence increases with age. There is roughly a 20 percent chance that aneurysms larger than 5.5 centimeters in diameter will rupture over the course of several years. That risk increases to 50 percent when the diameter is greater than 7 centimeters, Lee said. Smoking, high blood pressure, obesity, high cholesterol and emphysema are all risk factors for the disorder. Individuals also may be genetically predisposed to it.

Lee used the snorkel technique to repair it Vitullo's aneurysm, which was more than 7 centimeters in diameter. First, he made a small puncture in her femoral artery, just above her right thigh, through which he guided the main stent graft into the correct position above the aneurysm. Working in concert with Dalman, the team guided the snorkel stents into position alongside the main stent graft from the opposite direction, through small incisions in an artery beneath her left arm, to create pathways for blood to flow to the arteries leading to her intestines and right kidney.

Lee and Dalman have performed more than 60 snorkel procedures in the past three years and have been recognized internationally for their efforts in improving the technique.

"My experience with the operation and with Stanford has been great," Vitullo said. She had the surgery on Feb. 14, 2012, and spent five days in the hospital before heading home.

Stanford Hospital performs more minimally invasive repairs of AAAs than any other hospital in Northern California. "Stanford has the most robust portfolio of innovative aortic disease management procedures of any center in the state," Dalman said.

In addition to the snorkel technique and because of the extensive experience acquired by the Stanford vascular team in treating complex aortic aneurysms, Stanford Hospital was one of the first U.S. hospitals to have access to the Cook Zenith Fenestrated Aortic Endograft to treat complex AAAs near the renal arteries, which supply the kidneys. This stent graft, which was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, has fenestrations, or holes, on the side to provide blood flow to the renal arteries. Selection of hospitals to have unrestricted access to this technology was competitive, and Lee was the first U.S. physician to complete the proctoring and approval process to obtain full access to it.

Provided by Stanford University Medical Center