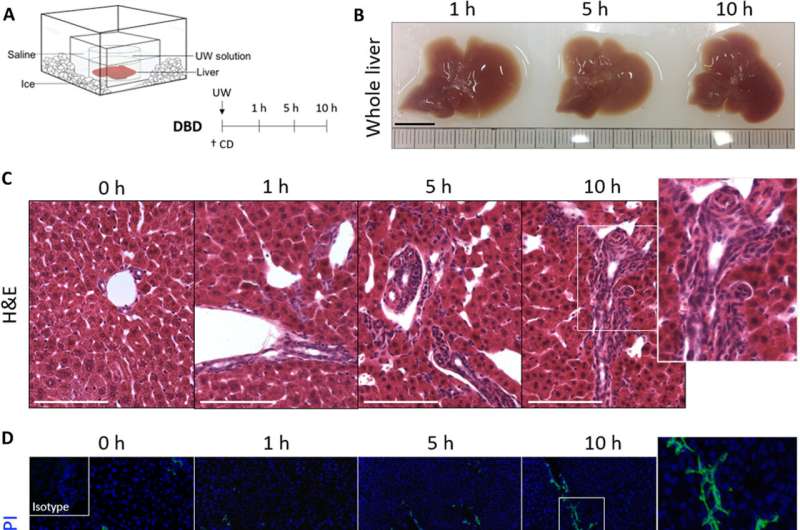

Cold storage conditions induce morphological changes in the anatomy of murine bile ducts. (A) Experimental setting for cold storage. Briefly, the mouse was culled by cervical dislocation (CD), and the liver was immediately perfused with UW solution and placed in a bag with UW. This bag was placed in a second bag with cold saline and surrounded by ice. Livers were maintained under these conditions for 1, 5, or 10 hours. n = 4 to 5 mice per experimental group. (B) Whole mouse liver after 1, 5, or 10 hours in cold storage. Scale bar, 1 cm. (C) H&E staining of mouse livers at 0, 1, 5, or 10 hours in cold storage. Scale bar, 120 μm. Far right: Digital magnification of the morphological changes in the biliary architecture. (D) Immunofluorescence of Keratin19 (K19) positive cholangiocytes (green). Scale bars, 250 μm. Isotype-negative control is shown in the top left quadrant. Far right: Digital magnification. (E) H&E staining at 10 hours shows cholangiocyte detachment in the biliary lumen. Right: Digital magnification. Far right: Immunofluorescence confirms the detached cells express the cholangiocyte marker K19 (green). Scale bars, 60 μm. (F) Number of bile ducts (BD) with detached K19-positive cholangiocytes during cold storage. **P < 0.01 (mean ± SEM). ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (G) Bile ducts isolated from livers maintained 0 or 10 hours in cold storage (CS), grown as organoids in culture and photomicrographed over 7 days. Scale bar, 120 μm. (H) Quantification of the average organoid size (pxl2) grown from bile ducts isolated from livers maintained for 0 or 10 hours in cold storage. **P < 0.01 (mean ± SEM), Student’s t test for day 7 (n = 4 mice each with three technical replicates in culture). (I) Percentage of total Ki67, PCNA, and LGR5 per 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)–positive cells in organoids grown from bile ducts isolated from livers cold stored for 0 or 10 hours. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (means ± SEM), Student’s t test. Credit: Science Translational Medicine (2022). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj4375

An existing drug could protect donor livers from damage during the transplantation process and reduce complications that occur afterwards, a study suggests.

The drugs, called senolytics, have been developed to target a key mechanism related to cancer and heart conditions, but in studies with mice researchers discovered it can also prevent the deterioration of a vital part of the liver during storage and transplantation.

The senolytic drugs were found to protect the liver's biliary tract, which drains waste from the liver. Failure of the biliary tract can cause a transplant to fail, resulting in the need for a new liver in nearly a quarter of these cases.

Liver preservation

Liver transplants are currently the only curative option for patients with end-stage liver disease. More than 6,000 people a year receive a liver transplant in Europe with 600 of those in the U.K.

Traditionally livers are kept in cold storage at 4 degrees Celsius prior to transplantation.

Previous studies have shown that there is a deterioration in the biliary tract in the time between the liver being removed from the donor and transplanted into the recipient, but the reason for this has not been understood.

To study the biological effects of liver preservation before transplantation, researchers from the University of Edinburgh used mouse models to mimic the procurement of livers, cold storage and transport.

Biliary tract

The team found that during organ preservation, liver cells called cholangiocytes, which maintain the function of the biliary tract, were most susceptible to senescence, an irreversible sleeping state that causes the cells to stop growing. Cold storage made senescence worse, leading to less regeneration of this type of cell after transplant.

When scientists gave the senolytic drugs, which block senescence, to mice prior to the liver removal procedure the biliary tract was persevered.

When the drug was tested in the laboratory on human livers not suitable for transplant the structure of the biliary tract was maintained.

Human trials

Experts say this suggests the drug treatment could reduce the risk of transplant failure due to biliary tract damage. They caution, however, that the safety and efficacy of the drug still needs to be tested in human clinical trials.

The team also discovered that despite being prone to cell death during cold storage, hepatocytes—the main type of liver cell involved in metabolism, detoxification and protein production—are able to regenerate as they were not as susceptible to senescence.

The work is published in Science Translational Medicine.

"A collaboration between scientists and surgical liver transplant teams led to this exciting finding. We hope to use this knowledge to help precious donor livers function well after transplant for the benefit of patients with severe liver disease," says Professor Stuart Forbes, director of University of Edinburgh's Center for Regenerative Medicine.

"As the number of usable livers needed for transplant does not match the number of donors of transplantable livers we need to increase the success rate of liver transplantation, which will improve the quality of life of transplant patients and save on the personal and financial costs associated transplant failure," says Dr. Sofia Ferreira, postdoctoral research fellow at University of Edinburgh's Center for Regenerative Medicine.

More information: Sofia Ferreira-Gonzalez et al, Senolytic treatment preserves biliary regenerative capacity lost through cellular senescence during cold storage, Science Translational Medicine (2022). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj4375

Journal information: Science Translational Medicine

Provided by University of Edinburgh