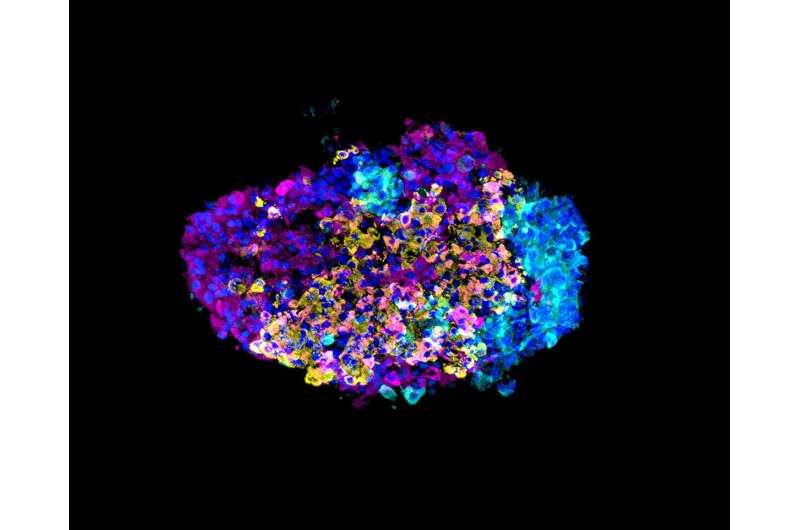

In 2014, Douglas Melton's laboratory at Harvard University pioneered a method to convert stem cells to insulin-producing beta cells. Researchers in the lab have now improved the method to enrich the final mixture for beta cells. Before the two-step enrichment process, cell clusters show fewer beta cells (in pink). Credit: Melton laboratory, Harvard University

A team of researchers led by Harvard University scientists has improved the laboratory process of converting stem cells into insulin-producing beta cells, using biological and physical separation methods to enrich the proportion of beta cells in a sample. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, may be used to improve beta cell transplants for patients with type 1 diabetes.

In 2014, Douglas Melton's lab showed for the first time that stem cells could be converted to functional beta cells, taking a step toward giving patients their own source of insulin. In that initial process, beta cells made up 30 percent of the final cell mixture.

"To improve from 30 percent, we needed to really understand the other 70 percent of the resulting cells," said Adrian Veres, a graduate student in the Melton lab and lead author of the current study. "Until recently, we couldn't take a sample of our cells and ask what cell types were in there. Now, with the revolution in single-cell sequencing, we can go from nothing to the full list."

A two-step enrichment

"We applied single-cell sequencing and molecular biology to describe the kinds of cells that we were able to make from stem cells. The beginning of manipulation is to always know what you're working with," said Melton, who is the Xander University Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology and co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Cells all contain the same set of genes, but cell types differ depending on which genes are active, or expressed. The researchers used single-cell sequencing to identify the full catalog of genes expressed in tens of thousands of individual cells. Then, they grouped the cells based on their expression patterns.

As expected, some of the cells had similar gene-expression patterns to cells that produce hormones in the human pancreas: glucagon-producing alpha cells and insulin-producing beta cells. (Unexpectedly, the researchers also identified a new type of cell that makes the neurotransmitter serotonin.)

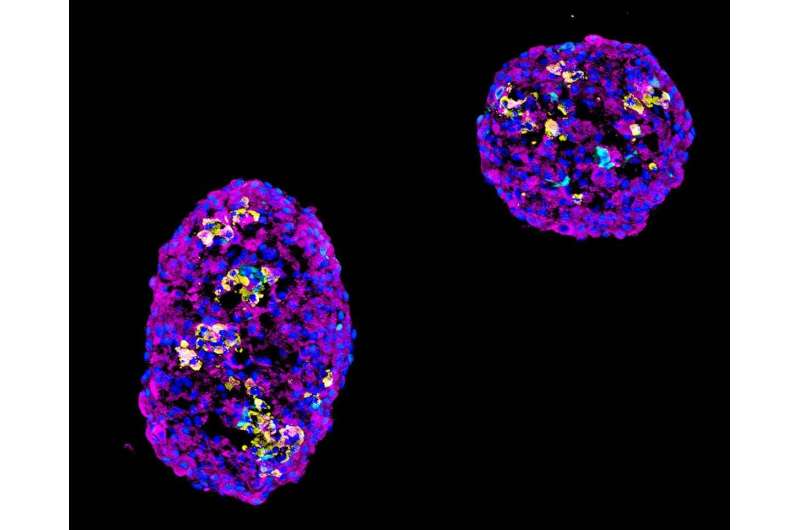

In 2014, Douglas Melton's laboratory at Harvard University pioneered a method to convert stem cells to insulin-producing beta cells. Researchers in the lab have now improved the method to enrich the final mixture for beta cells. After the two-step enrichment process, cell clusters show more beta cells (in pink). Credit: Melton laboratory, Harvard University

The team also found a protein that was expressed only on the beta cells. That meant they could use it as a biological 'hook' to fish beta cells out of the mix.

Collaborating scientists at Semma Therapeutics developed a second method for enriching beta cells: physically separating all the cells in the mixture, then letting them cluster back together.

That clustering enriched the number of beta cells. It was based on the hypothesis that hormone-producing cells are more attracted to each other than to cells that do not produce hormones.

Together, the two methods increased the purity of beta cells in a sample of converted stem cells from 30 to 80 percent.

"As we work toward putting stem cell-derived beta cells into patients, a purer mixture means that we can use a smaller, less invasive device to deliver the same amount of functional cells," said Felicia Pagliuca, Vice President of Cell Biology Research and Development at Semma Therapeutics.

Optimizing the mixture

The ability to control the percentage of beta cells in the mixture is the key finding in this study. Now, the researchers can focus on what the optimal mixture of cell types would be.

"The big question for us right now is whether 80 percent beta cells is what we want," said Veres. "Maybe you need more of the other cell types to help regulate the beta cells, so that they function correctly. We're going to find out how the cell types interact with each other."

More information: Charting cellular identity during human in vitro β-cell differentiation, Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1168-5 , www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1168-5

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Harvard University