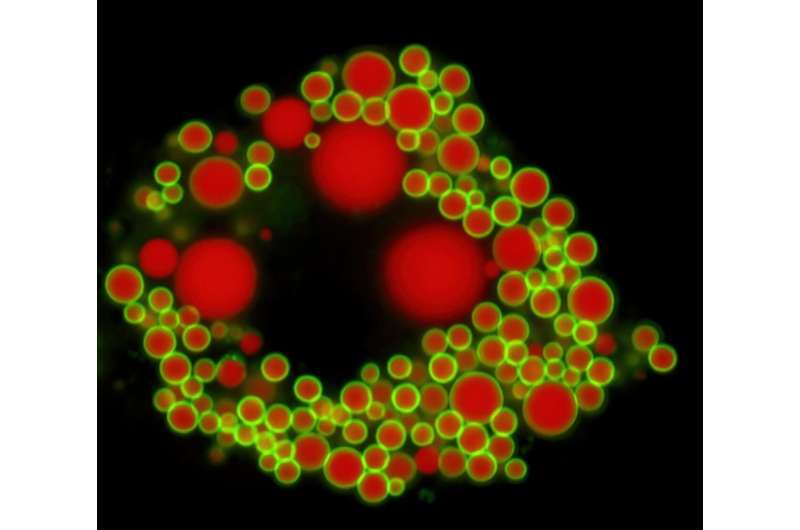

The inside view of a cell. Credit: (c) Johanna Spandl / Universität Bonn

Coconut oil has increasingly found its way into German kitchens in recent years, although its alleged health benefits are controversial. Scientists at the University of Bonn have now been able to show how it is metabolized in the liver. Their findings could also have implications for the treatment of certain diarrheal diseases. The results are published in the journal Molecular Metabolism.

Coconut oil differs from rapeseed or olive oil in the fatty acids it contains. Fatty acids consist of carbon atoms bonded together, usually 18 in number. In coconut oil, however, most of these chains are much shorter and contain only 8 to 12 carbon atoms. In the liver, these medium-chain fatty acids are partly converted into storage fats (triglycerides). Exactly how this happens was largely unknown until now.

The new study now sheds light on this: "There are two enzymes in the liver for storage fat synthesis, DGAT1 and DGAT2," explains Dr. Klaus Wunderling of the LIMES Institute (the acronym stands for Life & Medical Sciences) at the University of Bonn. "We have now seen in mouse liver cells that DGAT1 processes mainly medium-chain fatty acids and DGAT2 processes long-chain ones."

In their experiments, the researchers blocked DGAT1 with a specific inhibitor. The synthesis of storage fats from medium-chain fatty acids subsequently decreased by 70 percent. In contrast, blocking DGAT2 resulted in reduced processing of long-chain fatty acids. "The enzymes therefore seem to prefer different chain lengths," concludes Prof. Dr. Christoph Thiele of the LIMES Institute, who led the study and is also a member of the Cluster of Excellence Immunosensation.

Surprising side effect

Whether fatty acids in the liver are used at all to build up storage fat depends on the current energy requirement. When the body needs a lot of energy at a particular moment, the so-called beta oxidation is fired up—the fatty acids are "burned" straight away, so to speak. Medically, this metabolic pathway is of great interest. In diabetes, for instance, it might be useful to reduce beta-oxidation. This is because the body then has to meet its energy needs from glucose instead, causing blood glucose levels to drop, with positive implications for the disease.

As early as some 40 years ago, pharmaceutical researchers therefore developed a corresponding inhibitor, etomoxir. It binds to enzymes required for beta-oxidation, bringing it to a halt. However, it quickly became apparent that etomoxir had severe side effects.

The researchers in Bonn have now discovered a possible reason for this: They used etomoxir to inhibit the beta-oxidation of medium-chain fatty acids in mice, in anticipation of using it to boost the production of storage fat. "Instead, fat synthesis also decreased significantly, but only of storage fats with medium-chain fatty acids," Wunderling explains. "We therefore suspect that etomoxir also switches off the DGAT1 enzyme." In the future, he says, it will be necessary to pay attention to such effects when developing new inhibitors of beta-oxidation.

Also interesting is a finding published a few years ago by Austrian and Dutch scientists: They had studied patients suffering from chronic diarrheal diseases. In 20 of them, they found alterations in the DGAT1 gene that rendered it nonfunctional. "We now want to find out whether the impaired processing of medium-chain fatty acids is responsible for the digestive complaints," says Wunderling. This is because the DGAT1 enzyme is active not only in the liver but also in the intestine. Perhaps this is why its disorder causes diarrhea when sufferers consume medium-chain fatty acids. Wunderling: "In this case, they could possibly be helped quite simply—with an appropriate diet."

More information: Klaus Wunderling et al, Hepatic synthesis of triacylglycerols containing medium-chain fatty acids is dominated by diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 and efficiently inhibited by etomoxir, Molecular Metabolism (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101150

Provided by University of Bonn