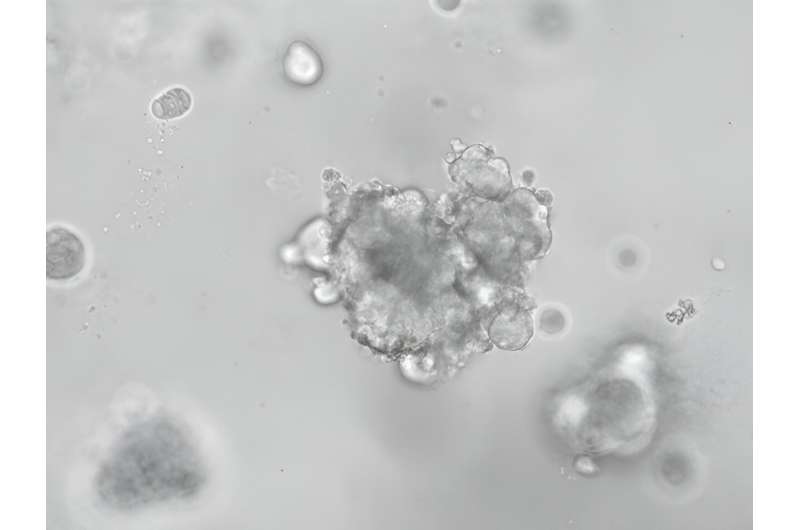

A culture of miniature neuroendocrine tumors. Credit: Talya Dayton, Hubrecht Institute.

The Organoid Group (Hubrecht Institute) and the Rare Cancers Genomics Team (IARC/WHO) found a way to grow samples of different types of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in the lab. While generating their new model, the researchers discovered that some pulmonary NETs need the protein EGF to be able to grow. These types of tumors may, therefore, be treatable using inhibitors of the EGF receptor. The results were published in Cancer Cell on 11 December 2023.

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are relatively rare tumors that can be slow-growing. However, some NETs can be aggressive and hard to treat. It is not yet possible to predict which tumors will become aggressive. There are very few models to study NETs in the lab, which limits research into this type of tumor.

Researchers from the Organoid Group (Hubrecht Institute) and the Rare Cancers Genomics Team (IARC/WHO), therefore, set out to develop new models to study NETs. They derived cells from patients with NETs and were able to culture them into 3D structures called organoids. These organoids mimic the behavior of actual NETs and can, therefore, be used to study this type of tumor in the lab. The new model is the first organoid model of the disease.

While generating the organoids, the researchers found that some pulmonary NETs need a protein called the Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) to grow.

"If we inhibit the receptor for EGF, some organoids die. Apparently, these organoids are dependent on EGF for their survival," says Talya Dayton, co-first author of the paper published in Cancer Cell. "We need further research to confirm our findings, but this may indicate that patients with EGF-dependent NETs could be treated with inhibitors of the EGF receptor." Inhibitors of the EGF receptor are already a course of treatment for other types of tumors.

Tumors are usually thought to be independent of growth factors. That some NETs turn out to be dependent on the growth factor, EGF is therefore surprising. "We think that their EGF-dependence might explain, in part, why some of these tumors grow slowly. We also think this might mean that one of how NETs can become aggressive is by becoming growth-factor independent. If they no longer need the growth factor, their growth may accelerate," Dayton explains.

The newly developed model for NETs provides a new way to study the disease in the lab. Dayton says, "This allows us and other scientists to understand the biology of these tumors so we can hopefully find effective therapies." Although further research is needed, the model already points to a new treatment route for patients with pulmonary NETs.

More information: , Druggable Growth Dependencies and Tumor Evolution Analysis in Patient-Derived Organoids of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms from Multiple Body Sites, Cancer Cell (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.11.007. www.cell.com/cancer-cell/fullt … 1535-6108(23)00398-7

Journal information: Cancer Cell

Provided by Hubrecht Institute