Game teaches surgical decision-making

A new, Web-based game could go a long way toward plugging what James Lau, MD, calls a gaping hole in surgical education.

The game, SICKO, is designed to help surgeons and surgical trainees practice making choices about surgery without involving actual patients. Lau, a clinical associate professor of surgery at the School of Medicine, hopes the game also will help surgery teachers better evaluate their trainees' skills, enabling them to do a better job of teaching.

SICKO, an acronym for Surgical Improvement of Clinical Knowledge Ops, is Lau's brainchild. He was inspired after playing Septris, a Web-based educational game about diagnosing and treating sepsis—infection-related systemic inflammation. He quickly recognized that its technology platform might serve as a tool to help surgery trainees, too.

Lau won a grant this year from the same body that funded the development of Septris, the Stanford Center for Continuing Medical Education, and, with the assistance of a team that included a Stanford surgical resident, a board-certified surgeon and the School of Medicine's Educational Technology group, built SICKO.

"Protocols can be taught," said Lau, who also directs the medical school's core clerkship in surgery and the Stanford ACS Education Institute/Goodman Simulation Center. "But the actualization of these scripts usually is not reinforced until actual clinical application. The gap between didactic learning and clinical application may affect the outcomes of the surgical diseases encountered. Yet sound clinical judgment is absolutely essential to ensure the highest standards of patient safety and care."

While simulation in various forms has become a widely accepted and available approach to teach technical skills to surgeons, the nontechnical portion of the discipline—what Lau calls clinical decision-making—has remained in the realm of surgery's apprenticeship model, without a practice format outside actual patient care. Such decision-making, Lau said, includes "how we triage the multiple patients we see every day, which of them to address first, how we judge acuity."

Today, there are no assessments of these nontechnical skills until the oral exams surgeons take as part of their board certification tests, several years beyond their first responsibilities for patient care. "We do mock exams," Lau said, "but we've no way to discern different knowledge levels of surgical trainees to see if their medical knowledge is what we would want in surgery. Once we get more and more people to play SICKO, we'll have more and more data about that."

Septris, released last year, was designed by Stanford clinicians and technologists. It has been played more than 21,000 times worldwide. Stanford medical students rated their knowledge significantly enhanced by its content. SICKO has more bells and whistles than Septris: Its platform can handle several levels of acuity and complexity; raw imaging, such as X-ray and MRI images; and analytic tracking of player actions.

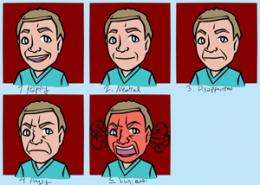

SICKO, like Septris, is designed to replicate clinicians' real-world experience, so players must cope with the care of multiple patients. Every decision a player makes is instantly commented upon by the graphic character called Dr. Sicko, who smiles or frowns, and then awards or reduces points for each decision. The game includes scenarios considered classic in acute surgical disease, among them appendicitis or cholecystitis. Role playing and module-based simulations have been used in the past to support continuing professional development, but Web-based interactive training such as Septris, accessible on smartphones, tablets and laptops, has proven to have great appeal.

Lau and his colleagues are already considering what other surgical specialties can be practiced with the help of mobile, Web-based games. The medical school's Educational Technology group also is working with medical schools outside the United States to translate SICKO into other languages.