The pain of chronic loneliness can be detrimental to your health

The changes came so gradually that, for a long time, Paula Dutton didn't realize she was in trouble. This was just modern life, after all—the cross-country distance from her close-knit family in Philadelphia, the end of a 10-year marriage that never quite jelled, the death of one parent and then the other. By the time Dutton, who now is 71 years old, retired from her job with an airline in 2011, she was lonely to a degree that shocked and frightened her.

"I just suddenly realized I was all alone and had no one around me and no one I could turn to," she says. "I had a lot of pity parties, I can tell you, and with all kinds of anxiety and depression, and I worked myself into a fever pitch in my loneliness."

The tipping point came with a panic attack so severe that it took a visit from paramedics to calm her down.

"I really felt like I might die," Dutton recalls.

The episode prompted Dutton to join the church near her Los Angeles home. The connection to the community brought her relief and felt like a solid step back from the void.

"I knew I was on the right track because hearing The Word and being reminded that I am not alone helped me in my pity parties, which got to be less and less often," she says with a laugh before turning serious again. "I had gotten to where, with the anxiety and the bad feelings, I thought, 'Is being so lonely making me sick?'"

In fact, it is quite likely that it was.

Loneliness and social isolation take a steep toll on the human body. Studies show that people who are chronically lonely have significantly more heart disease, are more vulnerable to metastatic cancer, have an increased risk of stroke and are more likely to develop neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's. Lonely adults are 25 percent more likely to die prematurely, while elderly people who are lonely die at twice the rate as those who are socially connected. All of which makes the spike in loneliness in American society even more alarming.

Researchers estimate that some 60-million Americans—one fifth of the population—suffer from the pain of loneliness. And with millions of Baby Boomers now facing a radically shrinking social world as they retire from the workplace, see their children disperse, lose friends and family members to illness and death, the rising tide of loneliness has all the hallmarks of a widespread and costly epidemic.

"Our culture is changing in ways that invite us—in fact, almost require us—to be more lonely and disenfranchised," says Steve Cole, PhD (FEL '98), professor of medicine and psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and director of the UCLA Social Genomics Core Laboratory.

Today, Americans live in increasing isolation. Extended families that once stayed within a few towns or counties of one another now span the country and, at times, the globe. Social media make our connections broader but not deeper. Visits on the front porch have morphed into "likes" on Facebook and stuttering images on video chats. Phone calls have been replaced by texts, which themselves are devolving from the shared bond of language into the flimsy abstraction of emojis. The result is that the web of meaningful connections that keep us healthy has frayed to the breaking point.

"Loneliness is a pending epidemic," Dr. Cole says. "The challenge is that the solutions are more nuanced and intricate than simply putting a bunch of lonely people together and telling them to connect."

What is loneliness? At its most basic, it is the lack of fulfilling social connection in people who yearn to feel connected. Our ability to feel lonely is an integral part of the human condition. At the same time, Norman Cousins, the late celebrated social commentator, author and adjunct professor of medical humanities in UCLA's school of medicine, noted that "the eternal quest of the individual human being is to shatter his loneliness." While this emotion is so fundamental to our being, it wasn't until the 1960s that loneliness became a focus of serious study. Letitia Anne Peplau, PhD, distinguished research professor of psychology in the UCLA College, is among the pioneers of research into loneliness. In 1978, she developed the UCLA Loneliness Scale to quantify an emotion that's so easy to feel but so difficult to define. The scale has been revised several times since, and it continues to be used by researchers to assess an individual's sense of social disconnect and isolation.

Loneliness may be fleeting, a moment of disconnection felt while in the midst of a crowd, or it might be the grinding anguish of isolation experienced over time. In either case, whether an internal and subjective emotional state or literally the act being alone, studies show chronic loneliness can be a killer.

"Humans are the most social of all animals in how they survive and thrive," Dr. Cole says. "We're not that big, we're not that strong, and we, as a species, have survived mainly by banding together to form little communities that, collectively, can do what none of us can manage by ourselves."

Dr. Cole studies the effects of loneliness at the molecular level, a deep dive made possible by the Human Genome Project. He began the work in the early 2000s, after a study revealed that closeted gay men with HIV died at a significantly faster rate than gay men with HIV who were open about their sexuality. The reason, it turned out, was the immune systems of the closeted men were not as robust as those of the openly gay men. Closeted men were far more sensitive to social threats, such as being rejected or even ostracized for their sexuality, than the openly gay men.

"The question became, is there something about threat-sensitivity that might make our bodies work differently?" Dr. Cole says. "And that concept turned out to be a very productive key to the biology of how loneliness turns into disease."

Working with John Cacioppo, PhD, founder and director of the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience at the University of Chicago, Dr. Cole studied how gene expression in a small group of lonely people differed from a group of non-lonely people. The results were startling.

"We found the key antiviral response driven by so-called Type 1 interferon molecules was deeply suppressed in the lonely people relative to the non-lonely people," Dr. Cole says. "But we also found that there was another block of genes that was not suppressed—in fact, it was greatly activated—and this block of genes was involved in inflammation."

Inflammation fuels disease processes in a host of devastating illnesses, including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's and cancer, Dr. Cole says. Inflammation is not the disease itself; rather, it serves as a kind of molecular fuel that helps the disease thrive and grow.

The study revealed that not only are people who are lonely markedly more vulnerable to outside threats such as viruses and bacteria, they also are under attack from within by their own bodies. But why?

"The best theory is that this pattern of altered immunology is a kind of defensive reaction mounted by your body if it thinks you are going to be wounded in the near-future," Dr. Cole says.

That is, our bodies see loneliness as a mortal threat. When we're alone, there's no one to help us to fight off that saber-tooth tiger or the hostile war party from the next village. Sensing that we are isolated and at risk, our bodies ramp up their defenses in anticipation of the wounds and infections to come. It was a pretty good survival tactic thousands of years ago. In the modern world, though, it's killing us.

"the level of toxicity from loneliness is stunning," says the University of Chicago's Dr. Cacioppo. A leading authority on the cellular mechanisms and physical effects of disconnection, he also is the author of Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (WW Norton, 2008).

"The mortality rate for air pollution is 5 percent," Dr. Cacioppo says. "For loneliness, it's 25 percent."

And yet, the emotional state of loneliness is crucial to human existence.

"To survive as a species, we very much want to have people who are so pained by thoughts of losing connections with each other that they are willing to fight off invading hordes," Dr. Cacioppo says. Loneliness also helps assure that enterprising souls who set off on expeditions of discovery will return home to share their newfound knowledge. "Loneliness reminds us how crucial it is to connect. It's what gives us our humanity," he says.

If the physical damage that loneliness causes is largely silent, why does being lonely feel so bad? The very language we use to talk about social disconnection is filled with words of pain and emptiness. You ache, you're wounded, your heart is broken, you feel hollow or empty, you're torn up inside.

In her research into social isolation, Naomi Eisenberger, PhD, associate professor of social psychology at UCLA and director of the Social and Affective Neuroscience Laboratory, found a surprising answer. Dr. Eisenberger created a study using an open-source virtual ball-tossing game called Cyberball. Although it looks like any other online game, it can only be played from the computer on which it is downloaded. It's a simple set-up—several players "toss" a ball back and forth within a group that includes a test subject whose brain activity is being scanned.

But Cyberball is rigged.

"At a certain point, the other players will deliberately stop tossing the ball to the subject," Dr. Eisenberger says. "As we measure the neural activity, we can look at the brain and see how it is changing when people are now being excluded, compared to a few minutes before when they were included in the ball-tossing game."

The result? The brain activity of the person being deliberately excluded looks strikingly similar to what is observed when someone is in physical pain. Just as important as the brain scans are each subject's verbal reactions. "There's a lot of variability to how people respond to being left out. Some get very upset and take it very personally, while some are much more able to explain it away, or say, 'I didn't care about them anyway,'" Dr. Eisenberger says. "We have the brain data and we have their self-reports, so we can also look at whether or not those two things go together."

It turns out that they do. Brain scans of the test subjects who reacted badly to being cut out of Cyberball showed increased activity in two regions of the brain associated with physical pain—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. Those who shrug off the exclusion showed little or no increase in activity in their pain centers.

"We think this is why people talk about rejection as literally hurting—because the brain processes emotional and physical pain in similar ways," Dr. Eisenberger says. "Because being connected is so important to us as a species, researchers think the attachment system may have piggybacked onto the physical pain system over the course of our evolutionary history, borrowing the pain signal to highlight when we are socially disconnected."

A surprising twist in this line of inquiry emerged when test subjects were given over-the-counter pain medications. It turns out that the same dose of acetaminophen that eases a physical ache will offer protection against emotional pain as well. When given acetaminophen over the course of three weeks, study participants reported fewer hurt feelings in the course of each day, Dr. Eisenberger says. In a repeat of the Cyberball experiment, the subjects who took acetaminophen showed a marked decrease in pain-related brain activity when they were excluded from the game.

The bottom line: We need to take social pain just as seriously as we do physical pain.

"When it comes to social pain, like when someone is suffering after a breakup, we can feel sympathetic at first, but after a while, we think, 'Oh, come on, get over it already, it's all in your head,'" Dr. Eisenberger says. "With social pain, you can't see the wound or the blood because it's emotional, but this work suggests that social pain is genuine suffering."

With the exclusion-equals-pain link established, Dr. Eisenberger now is looking into the pleasurable effects of social connection. "We know quite well that there are certain neural regions that activate to basic-reward processes, things like eating sweet foods or having sex or taking drugs," Dr. Eisenberger says. "These same kinds of regions also activate when you're reading loving messages from your close family and friends or when you're giving to charity."

This is vital research because studies show that chronic loneliness affects not only the body and the psyche, but it also alters behavior in social situations. Lonely people tend to be more guarded, are less able to read social cues and have such a heightened sensitivity to perceived rejection that they derail otherwise normal interactions. This makes finding a solution for loneliness a real challenge.

Getting together for lunch or a movie may help a lonely person survive an afternoon. But what about the long term? A promising program founded three years ago by Teresa Seeman, PhD, professor of medicine and epidemiology in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the Jonathan and Karin Fielding School of Public Health, may hold the key. "I've always been very interested in peoples' social relationships and the degree to which people who are socially engaged do better," Dr. Seeman says. "And it's certainly true this is a benefit that continues into older age."

With adults now living decades beyond retirement, the question becomes how to develop more ways for retirees to stay engaged.

How can retirees' sense of isolation be addressed in a significant way, one that lets them know they are making an important contribution?

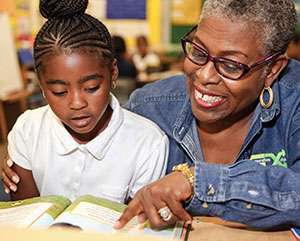

One answer turns out to be Generation Xchange, a program that has its roots in a similar initiative that Dr. Seeman was engaged in with researchers from Johns Hopkins University. Launched in Los Angeles three years ago, Generation Xchange recruits older adults who are at risk of being lonely to work with children in Los Angeles public schools. The volunteers undergo special training and commit to spending 10 hours per week in kindergarten-through-third-grade classrooms in South Los Angeles. "The project I worked on with my colleagues at Hopkins was fabulous," Dr. Seeman says. "When I looked around to see if there was something like that here in L.A., I couldn't find anything."

So Dr. Seeman went about recreating the program here. Soon, with initial funding from private donors who wanted their gift to improve the lives of older adults, Generation Xchange was launched. Based in South Los Angeles, the volunteers work in elementary schools that, eventually, feed into Crenshaw High School.

The program started out small—just one school with five volunteers. Three years later, 40 volunteers are working in four elementary schools, and principals throughout the area are clamoring for their own schools to be included. "The teachers love it, the kids love it, and we have principals lined up asking for the program," Dr. Seeman says. "The kids are thriving, and the older adults are having a blast."

The older adults benefit from work that is physically demanding, cognitively stimulating and socially rewarding, Dr. Seeman says. It also is psychologically beneficial every day that they come to work, as the volunteers see how their efforts are helping the children. Initial analysis of the Hopkins program in Baltimore shows the adults were more physically active, watched less television and reported an increase in meaningful social relationships, Dr. Seeman says. The children benefited as well. When compared with students whose schools were not part of the program, the children had higher test scores in reading and math. The researchers in Los Angeles now are planning an evaluation of the program here in the coming year. "With 40 volunteers, we now have a large enough number to take a look," Dr. Seeman says.

For Bertha Wellington, one of the five original Generation Xchange volunteers, no analytics are needed. Without a doubt, the program changed her life, she says. Now 68 years old, Wellington had been aware of her growing sense of loneliness and isolation for some time. "As an older person, you get to feeling the sense of loss of a portion of your life as the people you love, your friends and your family, move away or get sick or die," Wellington says. "I'm quite active, and I do have opportunities to meet new people, but it's not necessarily something that brings you the kind of closeness you truly need."

When she spends time in the classroom with the children, however, "the hours fly by," Wellington says. "Whichever portion of the classroom you're working with, the low achievers or the high achievers, they are hungry for personalized attention, and they just claim you as their own. These become important relationships because the children want the others around them to know 'that's my Mrs. Wellington, she comes to my school and helps me.'"

The bonds that are formed transcend school hours and boundaries.

"I was in a store once and these children were running around and misbehaving, and they ran right up on me and had to put the brakes on," Wellington recalls. She recognized some children from her classroom and gave them a questioning look. "They didn't want me to see that side of them, and right away they knew they had to clean up their act," she says. "Of course it goes the other way, too—you want to step right when you're with them, you want to set the best example."

The loneliness that once felt overwhelming now is gone, Wellington says. She credits both the work with the children and the relationships that have sprung up among the adult volunteers. "I really can feel the difference," she says. "We are concerned with each other and how we are doing. It's the kind of camaraderie that strengthens between us and gets to be quite strong."

Paula Dutton is among the Generation Xchange volunteers. She joined after hearing Wellington, her friend, tell stories about the satisfaction she got from working with the children. Where once Dutton's sense of isolation had triggered that panic attack so severe that paramedics were called in, she now finds herself in a widening and warmer world. She has a new man in her life and a deeper commitment to her church and revels in the meaningful work she does with Generation Xchange.

"I'm sitting at a point of happiness because of all of these things," Dutton says. "Before I was alone, and now I know I am not."