Study provides new insights into health system cost of living and dying in New Zealand

A just-published study showing how public spending on health varies by age and proximity to death raises interesting questions about the best use of taxpayer funds, the authors say.

Deciding and controlling total spending on publicly-funded health services is hard – deciding on how this funding should be distributed between young and old, people in good health versus those near death, and between prevention and treatment is harder still says lead author Professor Tony Blakely, Director of the Burden of Disease Epidemiology, Equity and Cost-Effectiveness Programme (BODE3) at the University of Otago, Wellington.

The study, published today in the New Zealand Medical Journal, provides important context to this decision-making, Professor Blakely says.

"The allocation of public funds to health services needs constant public debate, balancing the maximisation of health gains for each dollar spent against other values such as fairness, or the right to dignified death," he says.

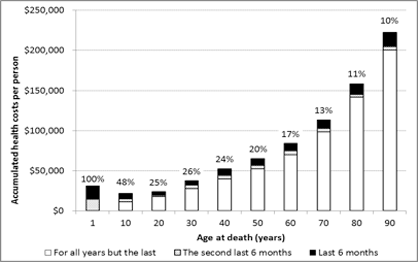

The study has revealed that someone dying at age 70 would have received $113,000 of New Zealand publicly-funded health services over their life – assuming 2007-11 costs had applied over their entire life. This compares with someone dying at age 90 having received $220,000 of services.

The amount of public health spending in the last six months of life was up to $30,000 for infants and the elderly.

It is commonly stated that something like 25% of health spending is in the last six months of life, Professor Blakely says.

"However, what we have found is that over the lifespan of a Kiwi citizen it was only in excess of 25% for deaths up to age 50. The vast majority of deaths occur at older ages."

For someone dying at age 80, of all the public spending on them over their life 'only' 11% was estimated to be in the last year of life, Professor Blakely says.

"Given that there is concern that spending in the last year of life may not be the best use of resources, it looks like New Zealand is doing fairly well in this respect."

New Zealand has a mostly publicly funded health system, including about $16 billion through Vote Health and Vote ACC. About two thirds of this funding can be attributed to individual citizen's health system events such as hospitalisation, lab tests and drugs. These events provided the data used in this study.

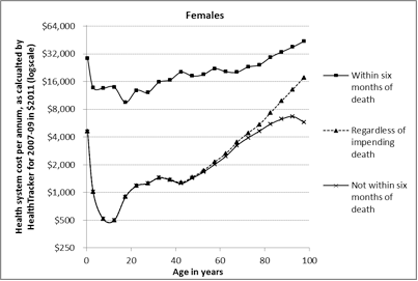

Treasury has estimated that Public or Government-financed health spending as a percentage of GDP in New Zealand might increase from 6.9% in 2011 to 11.1% in 2060. However, Treasury models do not allow for shifting out to older ages of 'near-death' costs due to people living longer, Professor Blakely says.

"We tested this assumption, but found that allowing for shifting of near-death costs only reduces projected future health spending by a few per cent. That is, under best-estimate future trends in population growth, disease and disability rates, and societal expectations, we are looking at a near doubling in publicly-funded health services in the next 50 years – a major issue for governments and Kiwi citizens."

Savings in health spending could be made at the end of life through the likes of advanced care plans. Such plans also usually increase quality of life near death, Professor Blakely says.

Spending more on prevention can also be cost-saving in the long run, he says.

"For example, reducing energy and sugar intake reduces diabetes rates, which reduces future health system costs – even allowing for people living longer and needing other services further into the future. On the other hand, demand on treatment services is virtually never-ending, meaning that savings in one area – for example fewer diabetes clinics - are usually quickly deployed elsewhere – for example more services for dementia."

Public debate on the allocation of public funds to health services is critical in a functioning democracy, Professor Blakely says.

"If the goals of Kiwis include increased quantity and quality of life, keeping health spending in check, and building a healthy and productive workforce aged up to 70 years of age or more to support the growing number of people aged over 70, prevention policies should be a key focus."